(RE)BIRTH OF THE CANVAS-BASED MURAL OF THE ESTONIAN STUDENT SOCIETY

Autor:

Hilkka Hiiop, Tiina-Mall Kreem, Andres Uueni

Year:

Anno 2017/2018

Category:

Conservation

The mural of the EÜS – an altar and a witness of the twists and turns of Estonian history

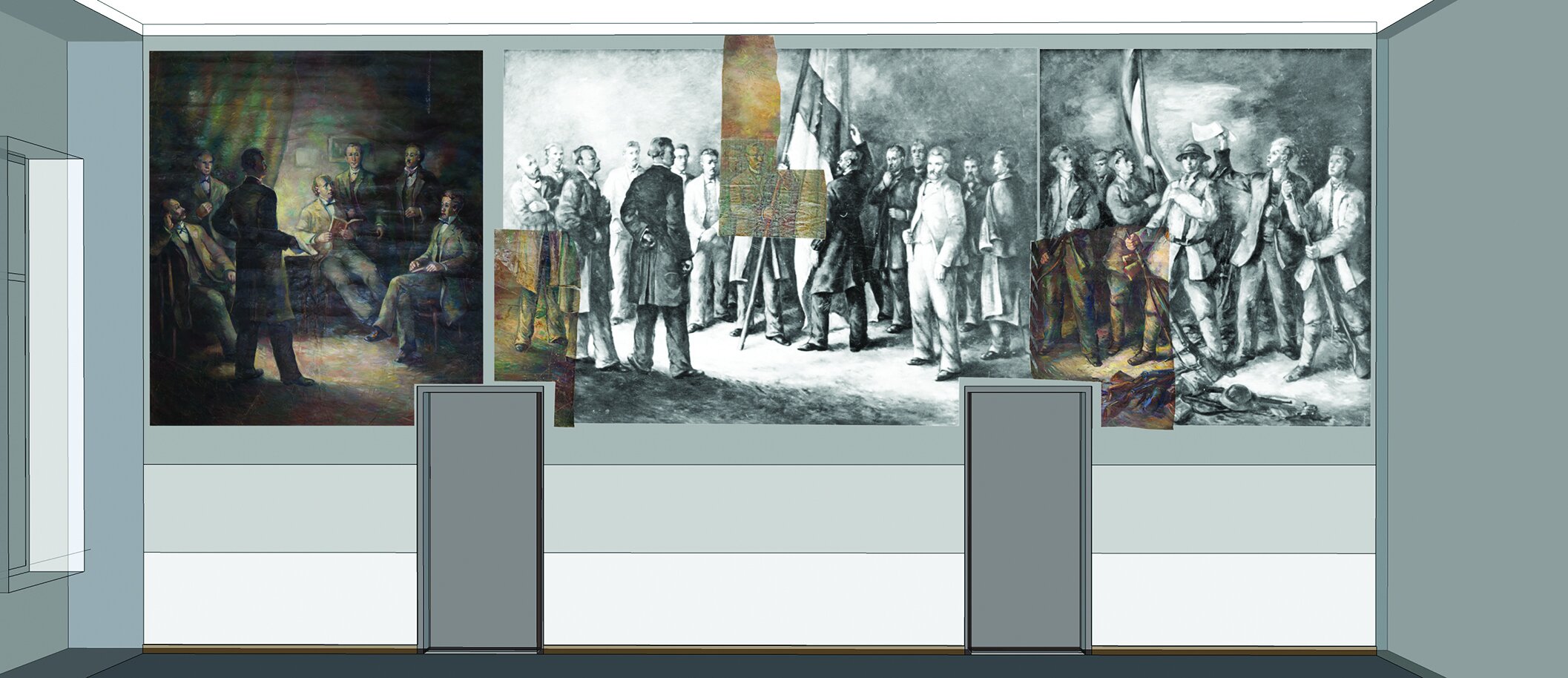

The very first enormous (almost 10m wide and 3m high) triptych on canvas ever painted by an Estonian artist was inaugurated in the house of the Estonian Student Society in Tartu on 9 October, 1938 [fig 1]. The mural commissioned by the alumni and painted by Aleksander Bergman (Vardi since the autumn of 1940) depicted three significant events not only in the history of the EÜS but also of the whole Estonian nation. The first of them was the first generation of Estonian intellectuals emphasising the importance of the national epic Kalevipoeg in 1870-1872, the events that motivated the first part of the triptych titled Kalevipoeg Evenings. The second was the consecration of the society’s flag in 1884, the tricolour that later became the national flag of Estonia, the painting titled Blessing of the Flag. The third part depicted the members of the society in corpore going into the War of Independence (Going to the War of Independence). The triptych mural depicting the sacred themes for the Estonian nation state impressed the viewer almost as an altar of Estonian history, even the more so, as we have nothing similar in its significance, realisation or size to compare to it.

Another point, its fate, also emphasises the comparison with an altar – the historical iconoclasm. After the communist coup d’état in 1940 the piece of art, be-lauding the Estonian nation state and its culture was removed from the wall [fig 2], rolled up and taken to the Estonian National Museum together with the rest of the Student Society’s movable property. It is not known, when exactly the triptych was destroyed – the parts depicting the consecration of the flag and going to the War of Independence were cut into pieces – they did depict something that the new regime wanted to erase from the people’s memory. Only one of the three paintings remained whole – the Kalevipoeg Evenings – that did not show any national colours. Besides, soviet authorities promoted the epic quite on their own implications.

The preserved parts of the mural, i.e. the Kalevipoeg Evenings, two pieces of the painting Blessing of the Flag and one of the Going to the War of Independence were transferred to the Estonian Art Museum. It happened in the course of the reorganisation of the museums that had been launched in the 1950s. They were actually registered only during the political thaw, i.e. in the 1960s. True, they were registered under their original titles already then. It goes without saying that no-one discussed either exhibiting or restoring them at that time.

When Estonian independence had been restored, the Student Society asked the Art Museum to return the preserved pieces of the triptych together with everything else of their property that had survived. Still, despite the overheated patriotic emotions, reopening the monuments to the War of Independence, exhibiting pieces of art portraying the epic and the tricolours everywhere, the mural was not displayed to the public. It was stored in the attic of the Society’s hall, waiting for better times. The painting Kalevipoeg Evenings together with the photos of destroying the mural were shown only once for a small number of people at the blue-black-and-white-topical exhibition dedicated to the 90th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia in Tartu-Narva-Tallinn (2008, curator Ellu Maar).

The mural was not quite forgotten, however. The Society sometimes discussed the artistic value of the paintings that had been commissioned by the alumni, who worked in Konstantin Päts’s propaganda section in the period of silence. It was not easy to appreciate the historical value of the be-lauded mural when there were people who still remembered how Jaan Tõnisson, a member of the society from Tartu and a serious critic of Päts had disparaged it. Contemporary critics were also a bit vulnerable, owing to the garishness of the soviet-time propagandistic art.

Several years passed before the mural started to interest art historians again. The first part – Kalevipoeg Evenings – was displayed at the opening exhibition of the Estonian National Museum, called National Romanticism in the Grip of History (2016, curator Reet Mark) and the reconstructed whole at the exhibition History in Images – Image in History in the Kumu Art Museum (2018, curators Linda Kaljundi and Tiina-Mall Kreem [fig 30]). The final aim of the reconstruction project was to return the piece of art to the Student Society for the Centenary of the Republic of Estonia, as something so closely connected with the history of the society, as well as to that of the republic. The aim was achieved – the mural by Aleksander Bergman was inaugurated in the Tartu hall of the Estonian Student Society on 28 September, 2018 [fig 31]. The inauguration ceremony was completed with the presentation of the book – The Big Picture. The Estonian Student Society’s Mural in 1938-2018 (authors Indrek Elling, Enn Lillemets, Tiina-Mall Kreem, Hilkka Hiiop [fig 32].

Something should be kept in mind, though. We cannot view medieval cabinet altars that have survived the iconoclasm in the same way their contemporaries looked at them. Thus we should not view the Estonian Student Society’s mural, almost totally destroyed in soviet times and restored 80 years later from the same position, as it was regarded in 1938.

Being aware of the historical value of the mural, an altar of the Estonian history and a great image of it, we could not close our eyes to its bad condition and not try to save it. Thanks to the alumni of the EÜS and the Toronto chapter’s financial support, the mural was reconstructed and mounted on its initial place.

2014-2018: Conservation and reconstruction of the mural

The story of restoration began in Tartu, in the historically original home of the mural. When the remains of the mural were unrolled on the floor of the great hall of the EÜS [fig 3] [fig 4] in the summer of 2014, the conservators were quite perplexed. Would it be possible at all to restore a triptych that had only one part preserved as a whole and some random pieces of the other two in addition? The pieces of canvas were in a wretched condition – creased, torn and with extensive paint losses.

A few more theoretical problems arose immediately as well. What could be the value of a mural in such a bad condition? Can the fragmentary original material be valuable in itself? Or does the value lie only in its history and its significance for the Estonian Student Society? Is the mural independently valuable or only in context of history and its initial place? And finally – could the fragments tell the story of their creation and destiny or should the story be recreated with the reconstruction of the mural as a whole?

Having held long discussions on our own and with some other art historians it was decided to restore the plot of the mural, proceeding from the historical context – connections with the hall of the Estonian Student Society and its history [fig 5] [fig 6] [fig 7] [fig 8]. The work started with the restoration of Kalevipoeg Evenings, the part that had preserved as a whole. The creased canvas was smoothed and placed on a supportive frame, paint surfaces were cleaned and losses toned [fig 9] [fig 10] [fig 11] [fig 12] [fig 13]. Then the black-and-white photos made of the triptych in the late 1930s were used for original-sized printouts on which the preserved three original pieces were ‘planted’. It was expected to make the initial significance and story visible that way, simultaneously retaining the fragmentariness that reflected the hard fate of the mural.

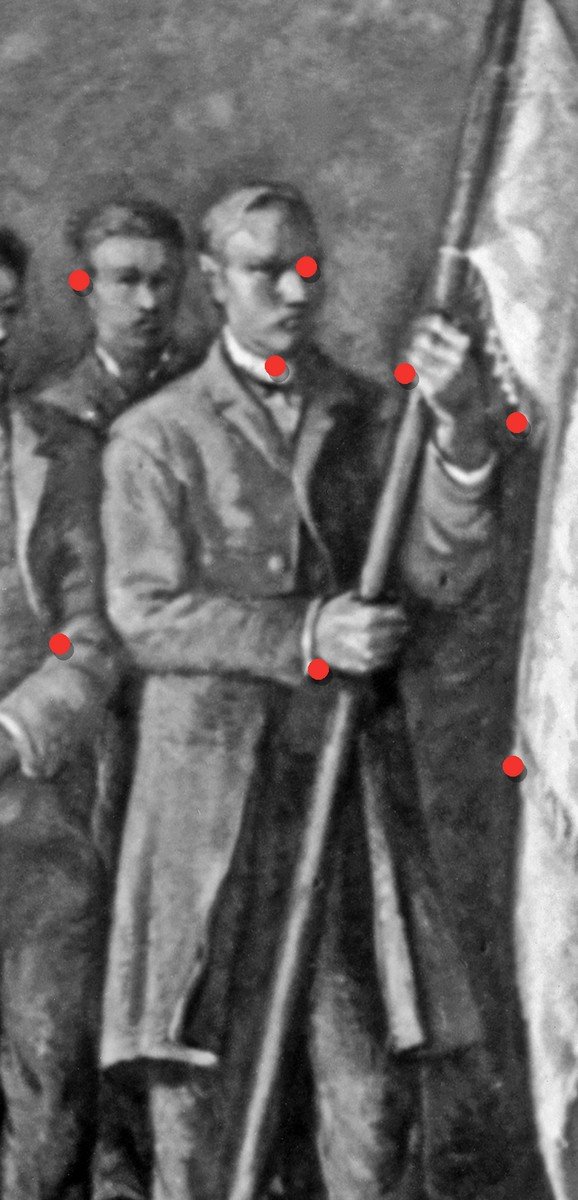

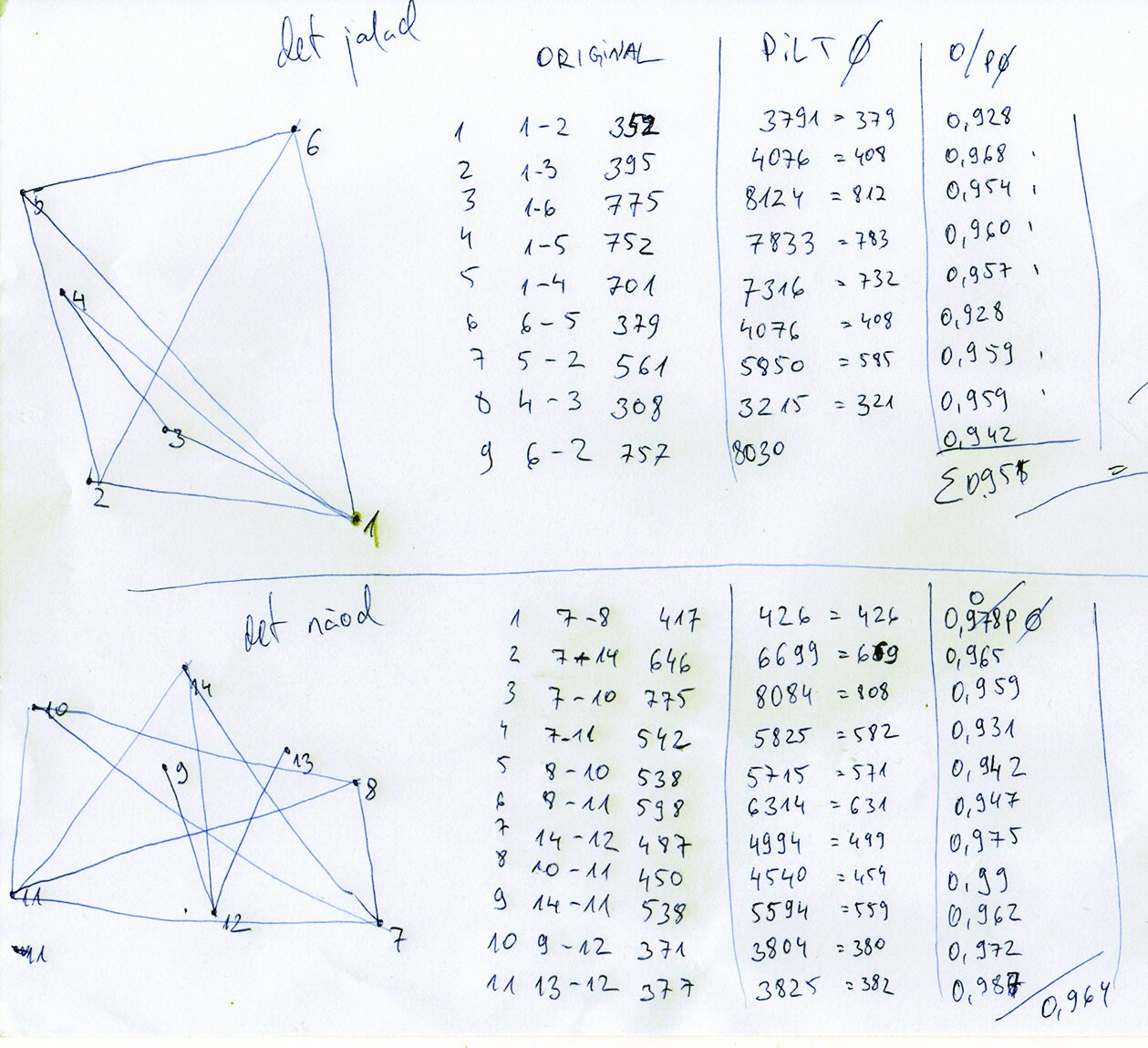

Restoration was technically complicated due to the immense size of the mural. Every preserved fragment compared to the whole mural seemed but a little piece of canvas, actually each was of the size of an average painting on canvas. The restoration of these pieces i.e. gluing together the tears, smoothing the creases, cleansing off the dirt, fixing the paint layer and toning the losses, was a labour-consuming process [fig 16] [fig 17] [fig 18] [fig 19] [fig 20] [fig 21] [fig 22]. Processing the photos of the two perished parts of the mural became a considerable challenge. The large scale demanded precision – every centimetre counted when the fragments were placed on the photo-canvas, every line was to match the images on the original piece but also consider these on the preserved Kalevipoeg Evenings and the proportions of the hall, where it would be displayed. The situation was made even harder by the fact that photographer Karl Hintzer had not taken exact scales into account when he took the photos of the almost 10m-long mural. He had chosen a place suitable for the parameters of his camera. Thus the displacement between the photo and the preserved fragments was almost 5cm in the proceeded files scale. As the only preserved photos had been taken according to the possibilities of the time, depending on the lens, lighting of the room etc, we had to consider contortion and make geometrical modifications on the digitised files. The only way to achieve the aim was to fix local co-ordinates, the so-called ‘beacons’ on the original fragments and on the files. The distances between these ‘beacons’ and the comparative material provided necessary information for the geometrical modification of every single digital file. Depending on the fragment the modification was complicated or even extremely complicated. Eventually, the variation error on the canvas printout and the preserved fragments was in between 2-5mm. All the variations between the fragments were in between 2-7mm that was good enough for a satisfactory result [fig 14] [fig 15].

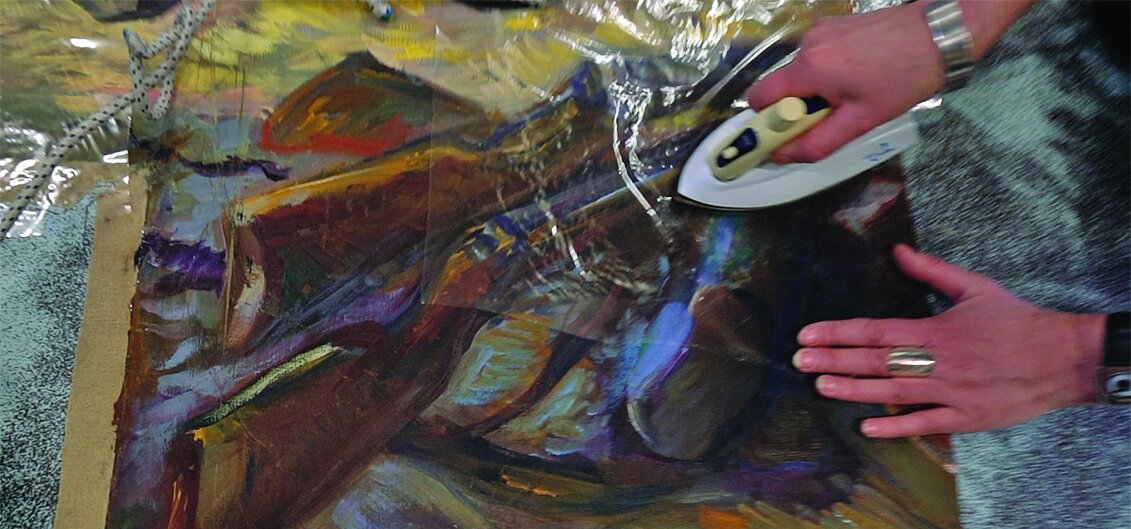

When the photos had been scaled, they were printed on canvas strips that were glued together. The chance fragments of the two destroyed parts were restored and planted on the photo-canvas with the thermoplastic BEVA-pellicle that activates when warmed up. Meaning that if needed, the original fragments of the mural could be removed from the photo-canvas to recreate the situation before the restoration [fig 23] [fig 24] [fig 25] [fig 26] [fig 27] [fig 28] [fig 29].

Although the mural had been displayed already at the Kumu exhibition History in Images – Image in History, the most anxious moments came when the mural was mounted on the end wall of the Estonian Student Society’s great hall. The hall had been changed in its proportions and interior design since the time the mural was painted – the ceiling had been lowered, mirror vaults added and the whole room redesigned in Art Noveau (locally called Jugend, design Sirja Uusbek) in the 1990s. To remount the mural in its original place an incision had to be made in the mirror vaults and the mural mounted at a rather extensive slant to fit it in between the ceiling and the doors. Thanks to the repeated measuring of the wall and the ceiling it fitted the bill. It was rather amazing to see how good it looked both physically and aesthetically. Whereas the artistic value of the mural still remained disputable at the Kumu exhibition, where it was too closely observed at a wrong angle, it now wholly proved itself above the side doors of the spacious hall.

Summing up

It should be emphasised that the resurrection of the mural required collaboration of many people and several institutions, lasting for four years in all, according to its strategic plan. The initial impetus to launch the restoration came from the mutual history project of the Estonian Art Museum and the University of Tallinn (in the framework of Estonian Republic – 100), the executors of which well understood that the Kumu exhibition would be impossible without that mural. The restoration itself needed the participation of many a specialist and master, including several PhD, MA and BA students from the Heritage Protection and Conservation department of the Academy of Art.

Simultaneously with the restoration of the preserved parts and the reconstruction of the whole mural, the process itself was recorded and the history of the mural was widely introduced and discussed. (An educational film, seminar in the EÜS hall, the Tartu conference of the Estonian Art Museum and the Kumu exhibition, several papers about historical images.) This was the only way – the rebirth of such an important piece of art and memorial returning into the cultural landscape needs lots of patience and explanations. The more viewpoints and variegated opinions the better.

We do hope that the restored mural of the EÜS will help us remember and evaluate the past but also encourage people to be innovative and ground-breaking in the work of saving and preserving the heritage.

See also video documentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6AzrK01DmY

[fig 33].

Team

Hilkka Hiiop, Üllar Juhanson, Merike Kallas, Tiina-Mall Kreem, Johanna Lamp, Frank Lukk, Villu Plink, Mihhail Stashko, Allan Talu, Taavi Tiidor,, Johanna Toom, Edgar Umblia, Andres Uueni, Varje Õunapuu.

Institutions – Uderna Puit, Serireklaam