STORY ABOUT TWO BABY-CAPS

Autor:

Liili Aasma

Year:

Anno 2017/2018

Category:

Conservation

Two mysterious caps arrived onto my worktable in the early spring of 2017. They looked rather wretched and worn, being deformed and dusty. One had quite a lot of material losses in the covering fabric and frill and the other’s decorative details were either missing or had unravelled. These two museum pieces – baby bonnets of the twin brothers Kristjan and Paul Raud – belonged to the collection of the Art Museum of Estonia. Evidently the caps had been sewn by the twins’ mother Henriette Loviisa Raud (née Treublut, 1834-1912). [fig.1] The caps had been donated to the museum in 1989 by Helge Pihelga, the daughter of Kristjan Raud. The miserable condition of them had made it impossible to display the caps in the Kristjan Raud House-Museum.1.

Something about the babies who once wore the caps

On 22 October 1865 a boy was born in a peasant’s family in Kirikuküla, Viru-Jaagupi parish. He was given the name Kristjan. The next day, on 23 October, his twin brother Paulus was born to the great surprise of their mother, who could not foresee the birth of twins at that time. According to the hearsay, she had not even guessed she was carrying twins and a whole day had passed from the first birth.2.

The Raud family considered education for children important. The boys got their primary education at the local Koeravere village school and continued their studies first at Viru-Jaagupi parish school, then at Rakvere County School and Tartu Modern Secondary School. Already at pre-school age the boys were really keen on drawing. The parents’ attitude must have been a considerable stimulus – it was a rare case indeed at that time for a father to buy his sons a box of watercolours. 3.

The boys excelled in their drawing-skills already in Viru-Jaagupi, then also in Rakvere and Tartu. Kristjan Raud’s memories from Rakvere school days note, “Sketches reflecting the life all around filled up more than one album.” 4. Kristjan had preferred drawing nature motifs, Paul sketching portraits. While studying in Tartu, the twins had an opportunity to get acquainted with several art collections belonging to local Baltic-German families. Collections of Professor G. Teichmülller and doctor Duhmberg especially impressed them.5.

Despite their similar background and studies the twin brothers had different characters and inclinations that took them onto the roads to different goals. They obtained their artistic education and training in different countries – Kristjan at the Petersburg Academy of Art in Russia and Paul at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in Germany. Later on they both attended numerous art courses and classes and worked as art-teachers at different schools.

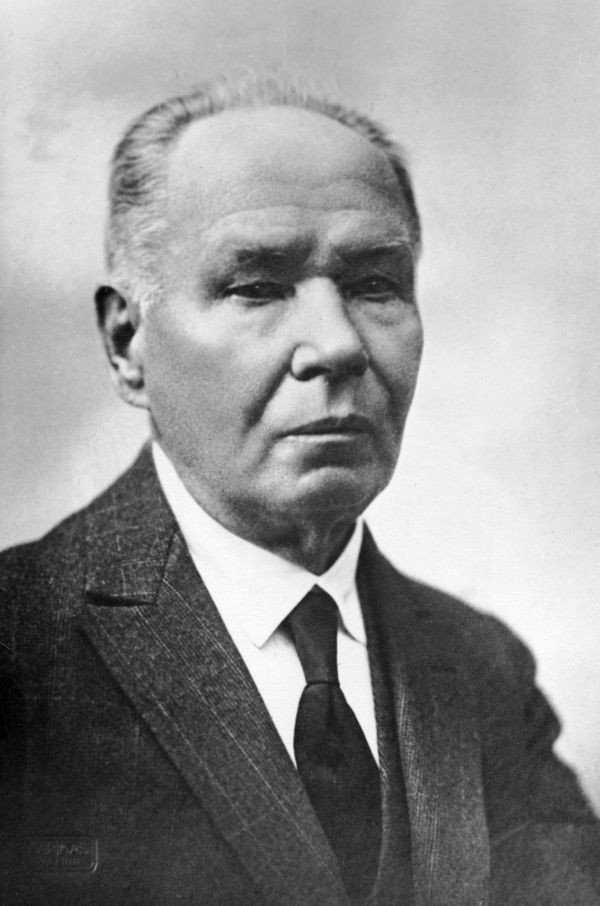

Kristjan Raud [fig.2] became one of the great minds in our culture, whose role in Estonian art could be compared with A. H. Tammsaare’s role in Estonian literature. He was the first to compile the heritage statute and owing to his keen interest in collecting material heritage the collections of the Learned Estonian Society and the Estonian National Museum were growing and increasing quickly. He was also active at the Tallinn Museum (i.e. the would-be Art Museum of Estonia) and was a leading figure and an honorary member of the Estonian Museum Society.

New-Romanticism together with symbolism and Jugend (Art Noveau) dominated in his style and creative work. He produced mostly charcoal- and pencil-drawings and, to a smaller extent, oil and tempera paintings. He preferred realistic topics but, at the same time, a big part of his work is based on Estonian folklore. His style is particularly well revealed in his illustrations made for the jubilee publication of the national epic Kalevipoeg. 6.

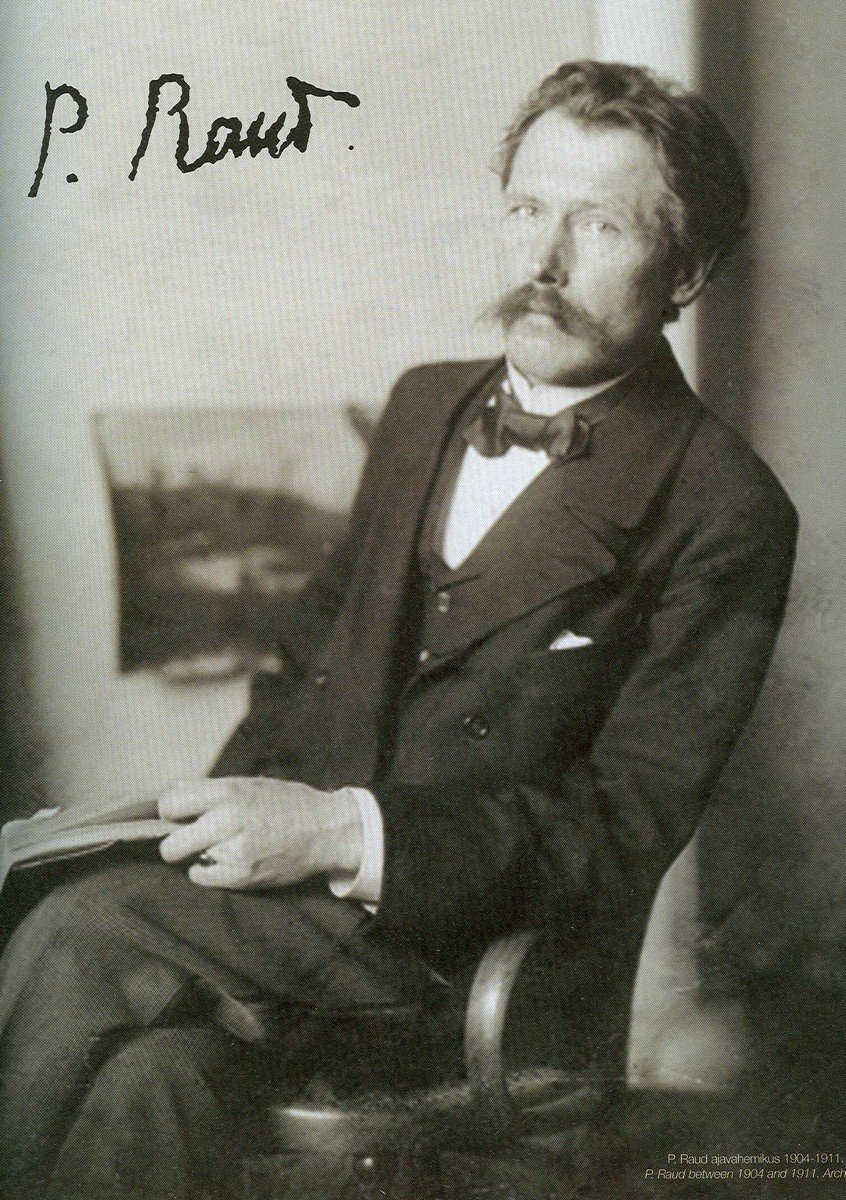

Paul Raud [fig.3] became acquainted with Baroness Natalie von Uexküll, an art-loving Baltic-German lady, in 1888. The baroness became Paul’s sponsor for his Düsseldorf studies. In 1894 Paul was able to fulfil his promise to make portraits of the baroness and her family and these portraits made his name well known as a portrait painter in the Baltic-German society. Paul was also active in the cultural life of Estonia. He was a member of the board of the Estonian Art Society, participating in all the bigger exhibitions in the 1920s. He worked as an art-teacher at several Tallinn schools in 1914-1923 and became a teacher of the State Industrial Art School in 1923. Realistic portraits of Estonian peasants, scenes from rural life at the end of the 19th century and landscapes make up the best part of his work.7.

The twin brothers Kristjan and Paul Raud have left an impressive mark in the cultural history of Estonia. They are among the first Estonian artists who built up their career in Estonia, although their talent and connections could have allowed them to participate in the art life of St Petersburg and Germany.

About the caps

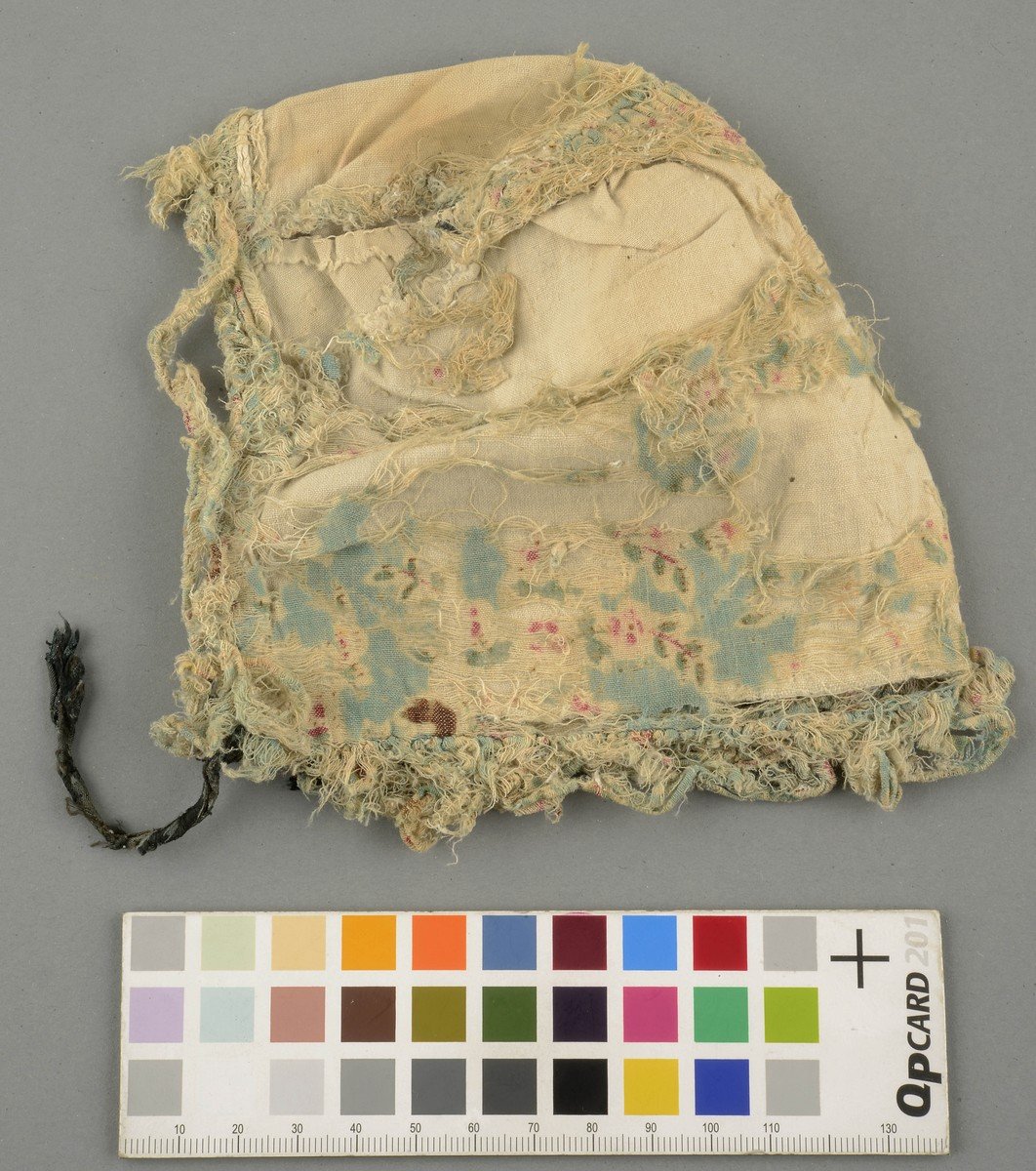

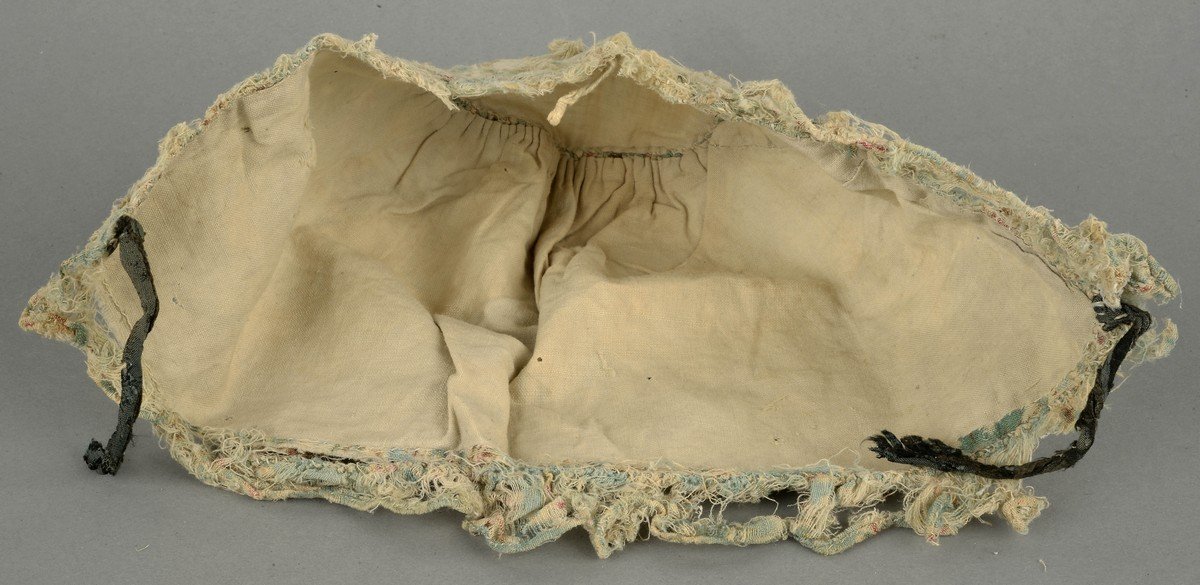

The logos of the baby-caps as museum pieces at the Art Museum of Estonia are as follows: a flounced cap EKM j 41197 KR 460/a [fig. 4] and a sectioned cap sewn up of gores EKM j 41197 KR 460/b [fig.12].

When working on them and making notes they became cap 1 and cap 2 – the convenient contractions would be used here further on.

Research and examination

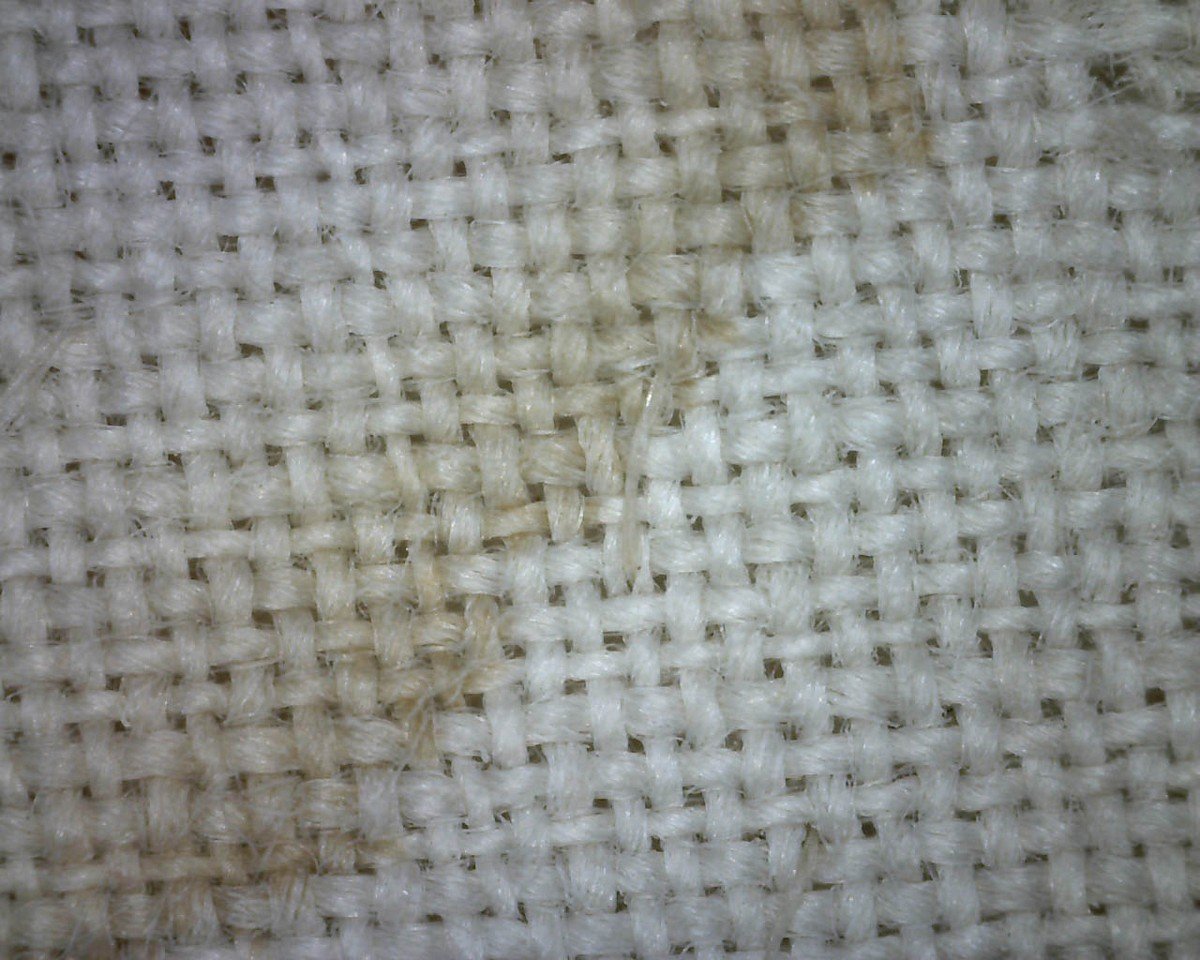

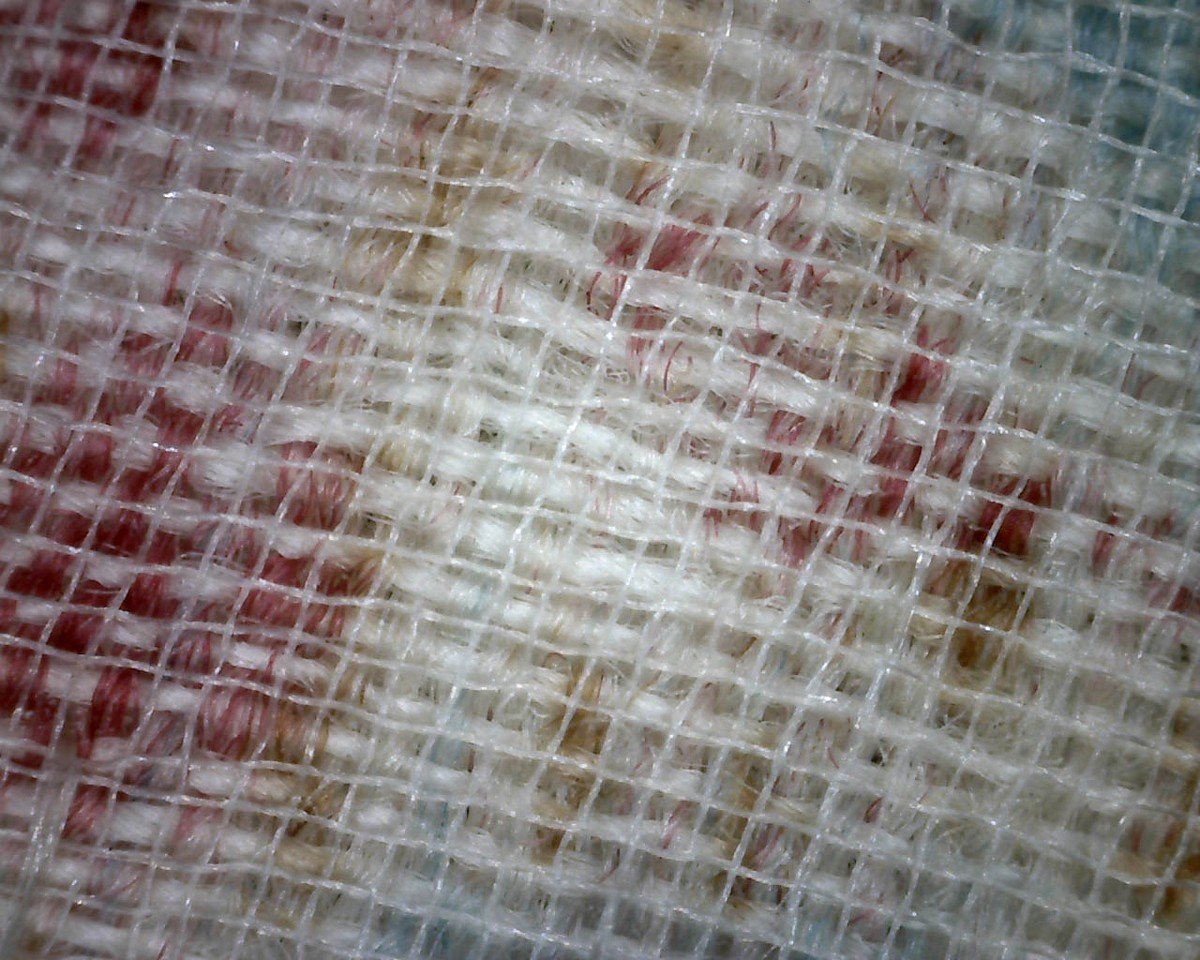

First of all the caps were examined through a 5x-magnifying lamp in order to determine their condition, extent of soiling and wear. As different fabrics had been used for making them, the damages in the woof structure had to be determined with the help of digital microscope off 50x enlargement. [Fig.19],

[fig.20], [fig.21], [fig.22], [fig.23], [fig.24], [fig.25], [fig.26]. Fibre preparations were made from the fabrics and the analysis was carried out on a 50-200x stereomicroscope.8.

To complement the examination of materials, a brief study of fashions 150 years ago was essential. This provided necessary information about the fabrics used at that time and ways of ornamentation for women- and baby-wear. I also consulted curators-historians of other museums to gain information on ethnic textiles in general and baby-bonnets in particular. Bibliography on folk costumes and photos of the MulSi were studied. The Kanut Centre co-workers with their variegated experience at examination and conservation of textiles, were a great help in practical issues.

Cap 1

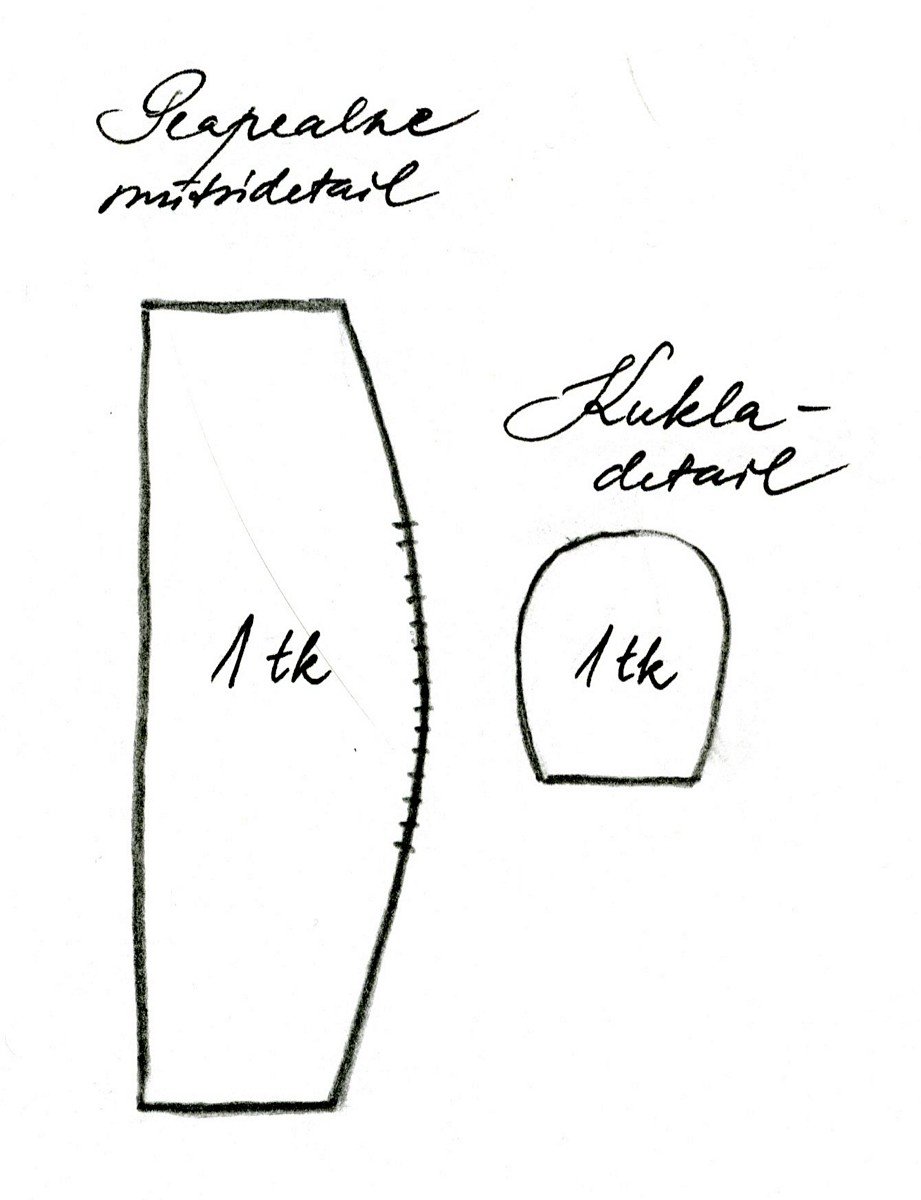

The hand-made cap was made of light blue and white cotton print fabric. The upper layer has an ornament of small leaves with pink and amber blossoms on twining green stalks. The cap consists of two separately cut parts – an oblong piece, a bit rounded at the end for the crown and a rounded piece for the nape [fig.5], [fig.6], [fig.7]. All the details have been sewn on natural white cotton lining [fig.8]. The cap has been gathered at the nape and edged with a narrow ruffle [fig.9]. Black silk ribbons were attached to tie the bonnet on [fig.10], [fig.11]. A tunnel for the gathering string, made from the lining material is inside the nape detail. The string that exits the tunnel in its centre has been tied into a tiny bow.

Cap 2

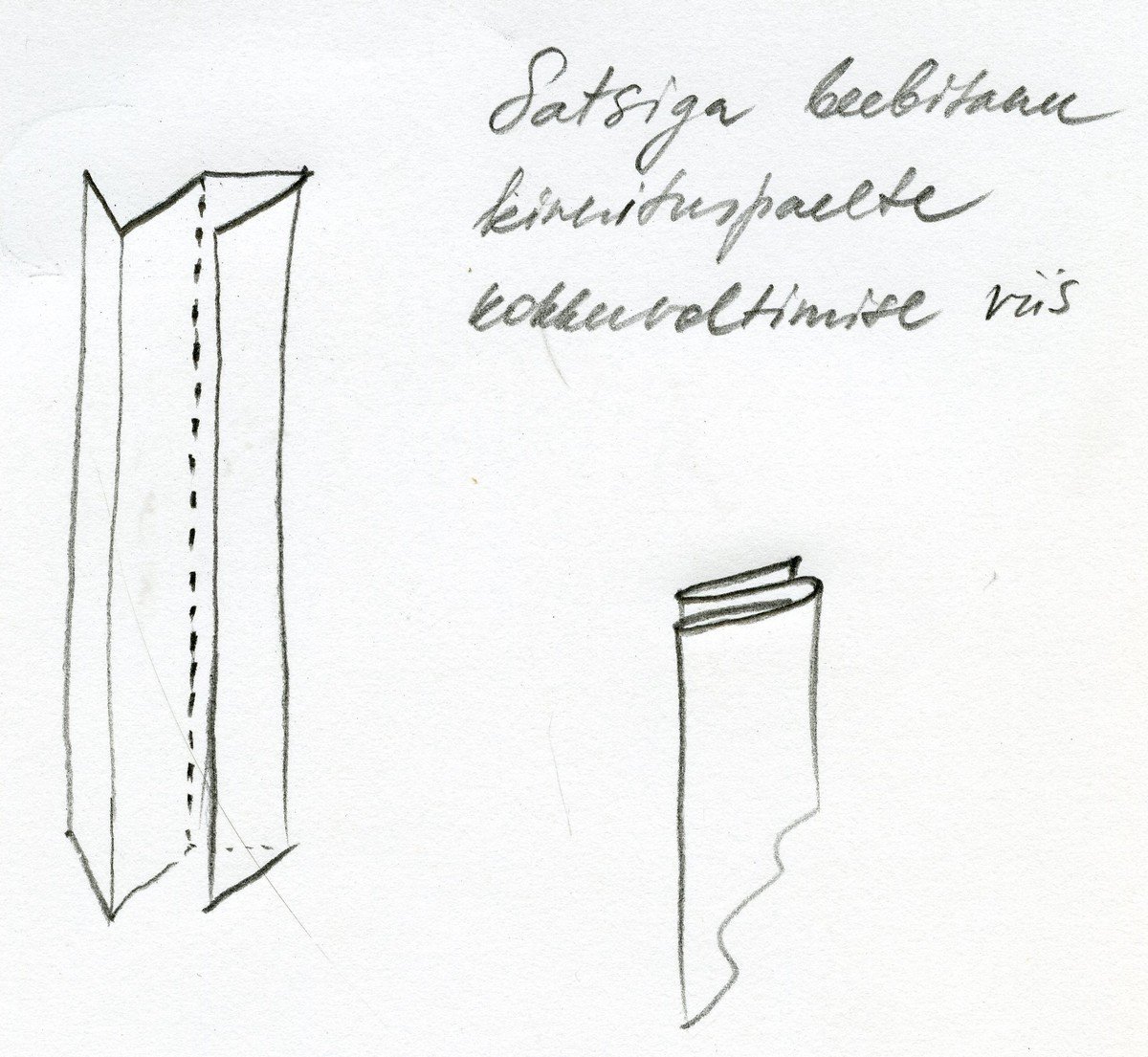

This cap has been sewn of five wedge-shaped gores. The three frontal ones are of silk – a light lemon-yellow piece with tiny red and blue rhombic ornaments woven into it is in the centre and two light russet-coloured gores with in-woven ornament are on the sides [fig.14]. The back gores that follow the nape line have been made of thin cotton material that shows reddish-pink plant ornament on white ground [fig.15]. The cap has been edged with light russet-coloured silk and the mustard-coloured silk ribbons to tie it on have been attached to the edge [fig.12].

All the connecting seams and the whole edge of the cap have been decorated with narrow bobbin lace that is fixed with a few stitches at every 1-2cm. The nape of the neck had been decorated with a tassel or tuft, combined of tiny laces of the cap’s fabric. [fig.16]. A few of the narrow laces had become loose and I guess they might have formed another tassel on the crown, as there are still some particles of thread there [fig.17].

The lining made of thin, white-and-blue-chequered cotton fabric followed the cut of the gores, while every lining gore was stitched separately with overcast stitch [fig.18]. A thin layer of cotton wool had been set between the upper gores and the lining gores (the seams still showed some fibres of it and it could also be felt when touching).

Conservation

Cap 1

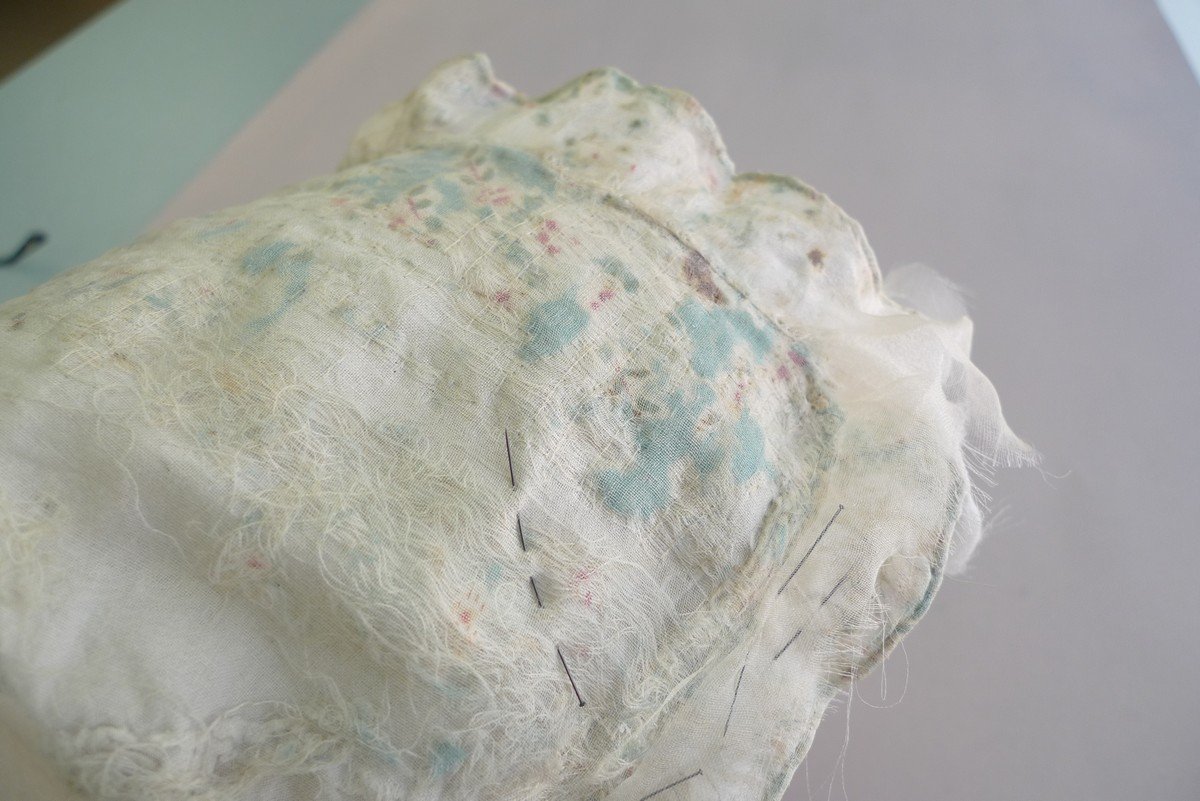

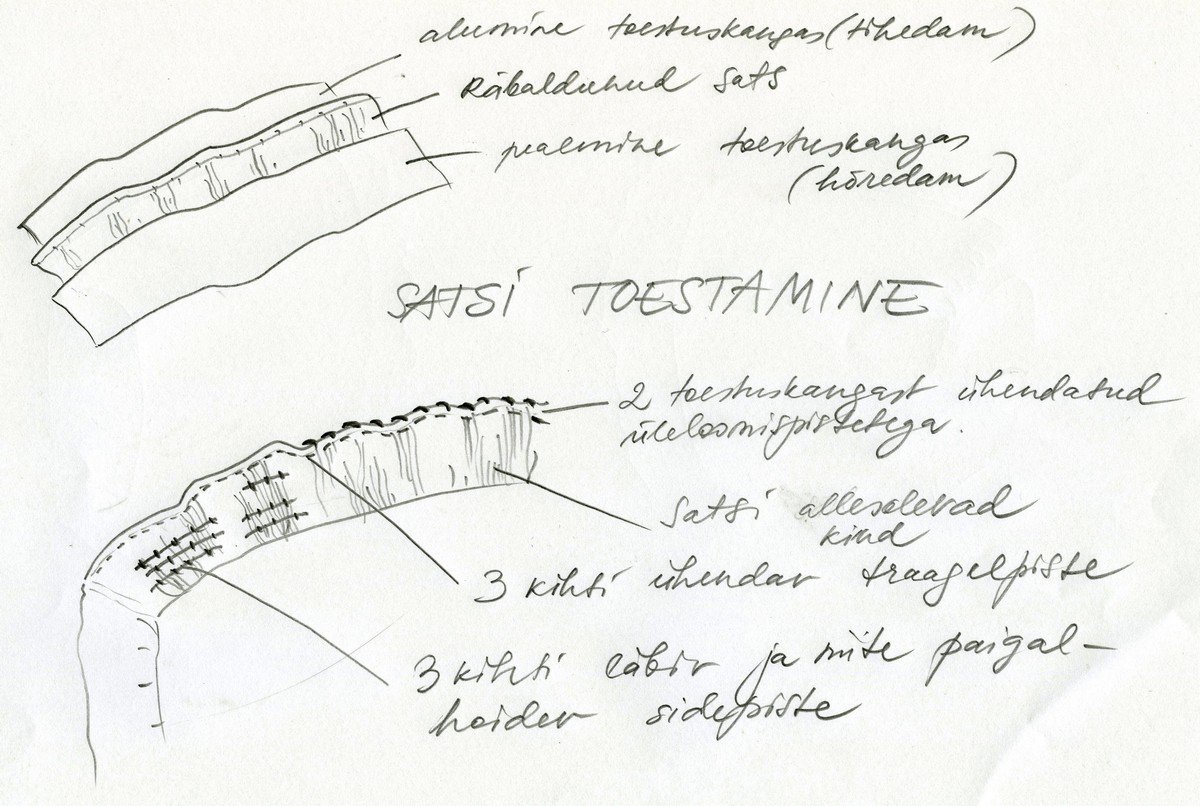

It was creased and dusty, it had lost a part of its weft and become brittle, obviously due to the damages of light. The right side bore bigger damages, having loose soiled thread-blobs all over. The same can be said about the ruffled edge that was kept together only by a rolled welt. Despite its wretched condition it was still decided to give it a wash, that way making it possible to give it a better shape and stretch the surviving threads.9. For drying and stretching a head-size shape was made of soft cotton fabric [fig.27]. The shape was used for both caps throughout the conservation process for shaping and supporting the fabric losses. The crown of the cap was covered with new fabric only on the surface of the original material [fig.28], the flounce, however, was covered on both sides. The preserved loose parts and threads were fixed with couching in between the two supporting layers [fig.29], [fig.30], [fig.31]. Natural silk veil10. was used for the supporting material [fig.32]. Threads for darning and fixing were unravelled from the same material. The tying ribbons were removed temporarily to support the otherwise inaccessible spots.

Cap 2

The textile fabrics of this cap were in a better condition compared to the first one but its ornamenting details seemed even worse. First of all dry cleaning with a vacuum cleaner with its smallest brush end piece was used. After that the surface was worked for shaping with damp cotton wool. Most attention was paid to the ornamenting details that were cleaned, stretched and shaped (i.e. the lace was set in flat folds) one by one. For the lace made of silk threads tiny filter-paper rolls helped the process along [fig.33], [fig.34]. Having stretched the lace, I fixed it on the cap in the same way as it had been done in the second half of the 19th century, i.e. in flat folds [fig.44]. The brittle lace was braced with 2% Klycel G-ethanol solution that provided it some surface (mechanical) firmness. The tassel on the nape and the ribbons that had formed the tassel on the crown were dampened and stretched. The ribbons were modelled into a tassel after the preserved tassel and the new one was attached on the crown of the cap [fig.46]. The tying ribbon that had several fabric losses was placed on a suitably-shaded silk fabric, fixed with couch stitch and folded in the way the original ribbon had been before it was attached to the cap [fig.35], [fig.36].

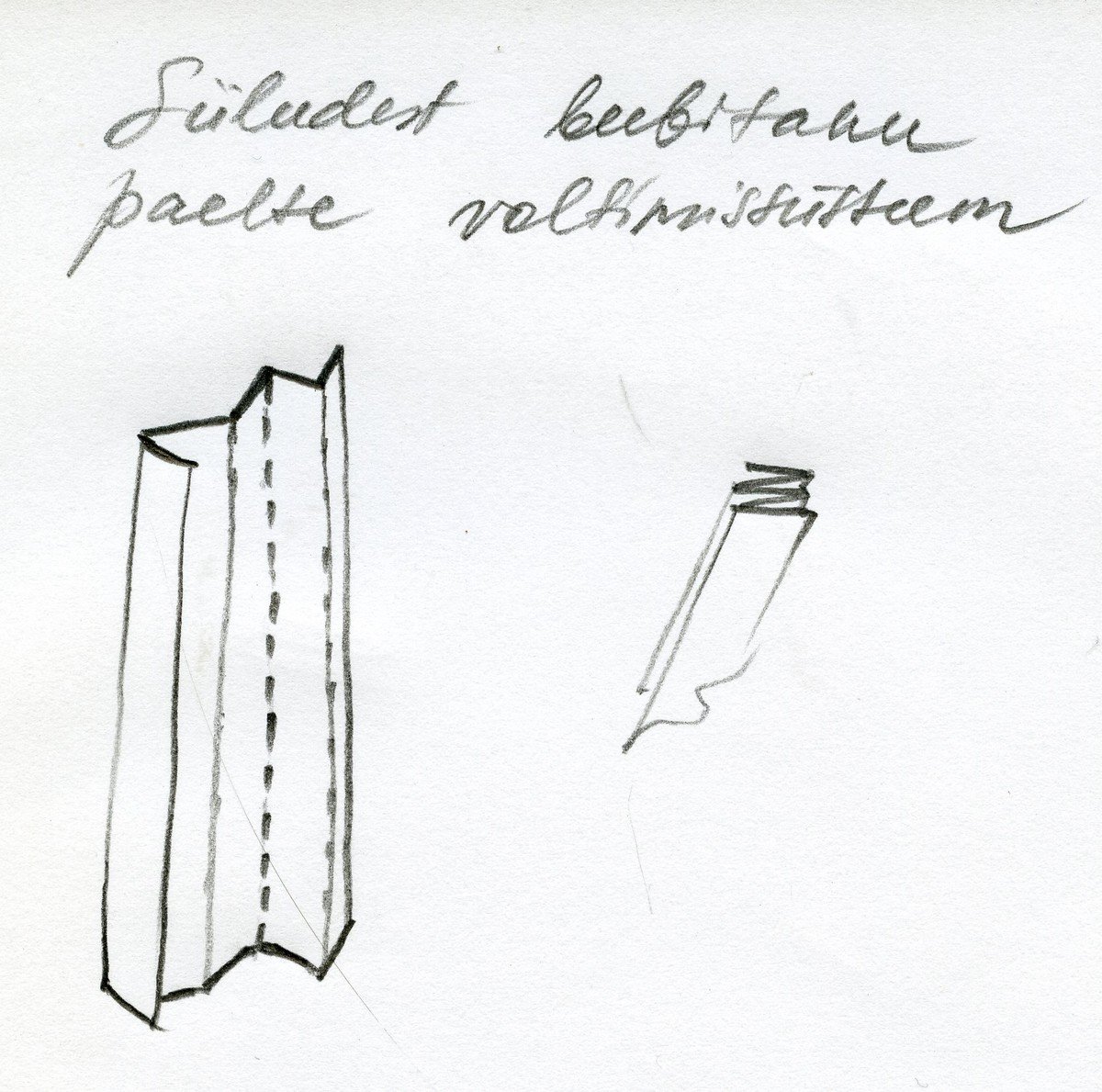

Finishing touches for storing

While working on the caps it became clear to me that they could not be stored folded in small boxes any longer. After some discussion with colleagues it was decided to make two fitting-sized shapes of papier-mâché [fig.36] for support.11. The head-shaped casts were covered with sheet wadding and cotton stocking fabric and fixed on round cardboard sheets with the numbers of the objects [fig.38], [fig. 43]. The supporting shapes will grant safer handling of the objects in the future and prevent them from being deformed. In this way they can also be displayed to be visible from each side [fig.38], [fig.39], [fig.40], [fig.41], [fig.43], [fig.44], [fig.45], [fig.46].

The museum was suggested to obtain storing boxes in a fitting size for further storing 12. [fig.45], [fig.46].

Some ideas that occurred in the course of work

The dissimilar cutting of the two baby-bonnets made me think that the mother had been preparing for one baby, either a boy or a girl. But in this case twin boys were born and so both bonnets were taken into use.

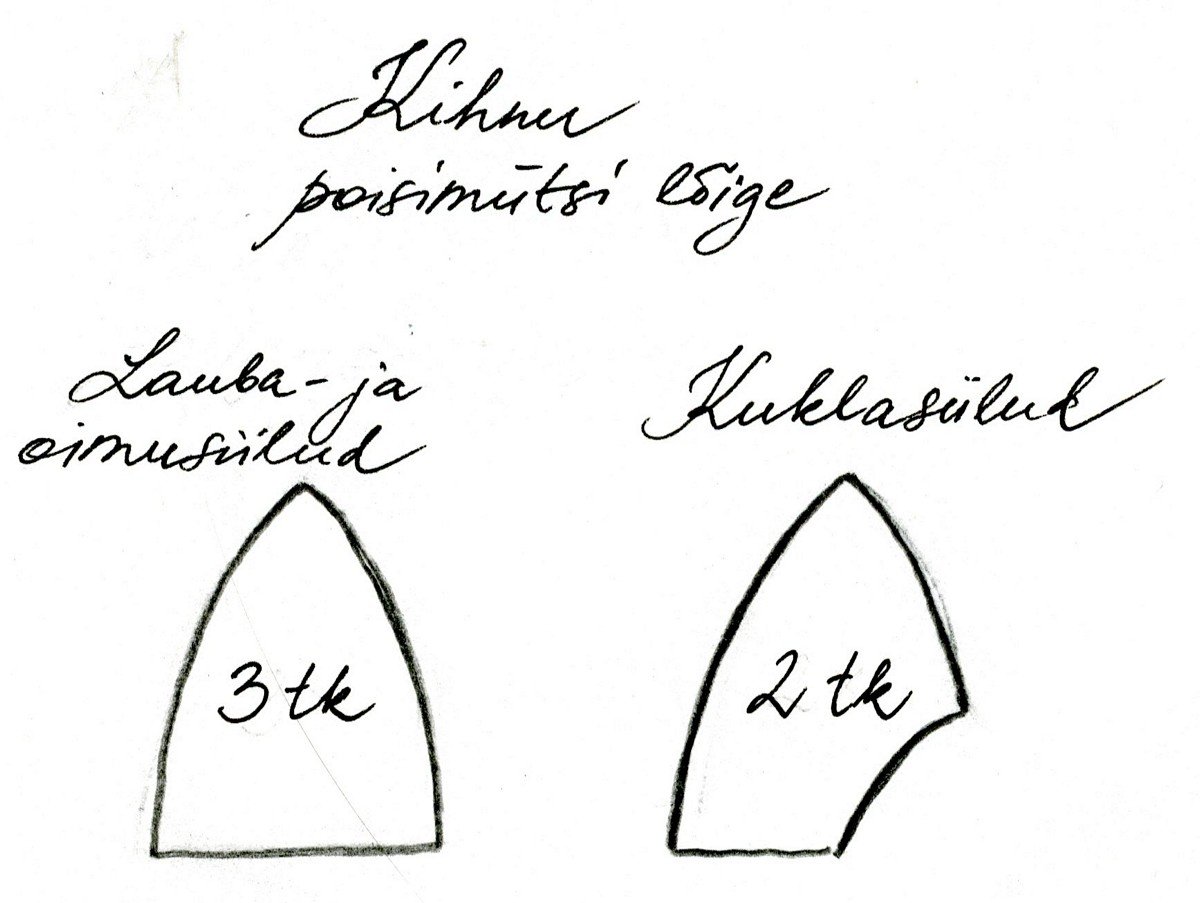

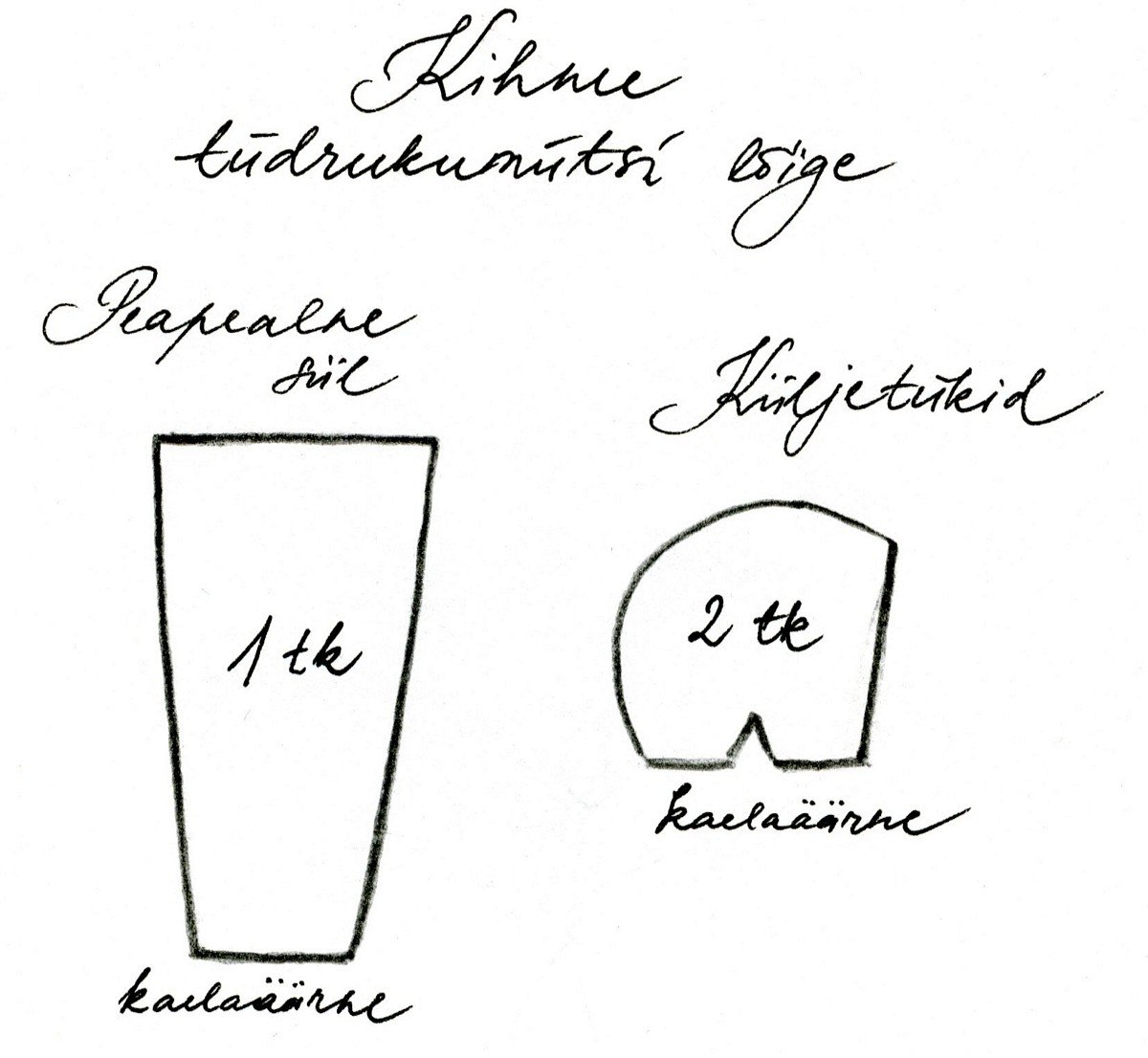

The idea about both sexes of the caps came to me when I learned about the still-existing Kihnu Island custom to make different caps for baby-boys and baby-girls [fig.48], [fig.51]. The Kihnu cap for boys always consists of five bordered gores and there must always be a tuft or a button in the centre of the crown. 13.

The same kind of information comes from the island of Muhu – before the baby was born the mother (or the would-be godmother) made two caps – one for a boy, the other for a girl. They say that bonnets for boys were more beautiful, sewn of gores and with tufts on the crown [fig.53], [fig.54]. Bonnets for baby-girls had a simpler cut. The colours were certainly the bright ones, typical of Muhu – mostly coral and orange, some yellow and white included, decorated with lace, zigzagging cord, piiprelles14. and spangles and buttons 15..

As the bonnets come from North Estonia, I considered it sensible to seek for corresponding material on the southern coast of Finland as well. The connections between the two countries are centuries long. Baptismal bonnets in Finland, depending on the sex of the baby, were also dissimilar. The cap for boys was made of six gores, the one for girls of an oblong piece for the crown and nape and two rounded sides. The material for older baptismal caps was in-woven patterned silk and the caps were bordered with silver or gold lace. The collections of the Finnish National Museum contain examples from the 17th century even. The baptismal cap was essential, as the baby’s head was to be covered. The cap was removed only for the brief christening process during which a godparent was holding it and then put it quickly back on the baby. The meaning of the baptismal cap began to disappear in the second half of the 19th century. 16.

The same difference in bonnets – i.e. dissimilar ones due to the sex of the baby – were know also in Sweden. “ The best way to make a difference between a baby boy and a girl baby was to look at their bonnets. The ones for the girls always had two sides, joined by a wide central piece, the boys’ caps consisted of several strips that were brought together at the crown. An expecting mother usually had two different caps ready, so that the baby would get the right one from the beginning.” 17. [fig.55].

Cap 2 made of gores on the working table was quite similar to the Kihnu boy’s cap – their three frontal gores are longer and the two nape ones shorter and following the nape line [fig.48] and [fig.50]. The Kihnu cap also has a border and a tuft. The tufts of the conserved cap 2 differ from the ones of the Kihnu cap, as the latter’s tuft has been formed of rounds, cut out from different fabrics and laid upon each other decreasingly [fig.49]. Cap 1 does not exactly resemble the Kihnu girl’s bonnet [fig.51], [fig.52] but it might be modelled after women’s everyday bonnets from central Europe and Scandinavia

[fig.56], might be even according to the more pompous night-caps, known also to our noble families [fig.57]. It seems that just these caps with rounded nape pieces have been the forerunners of our cap 1 and many other similar ones. They had spread all over Europe and those worn in the Victorian times in England are still called Victorian bonnets. This type became the widest-spread model for baptismal caps in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [fig.48], [fig.50].

Could the model for a boy’s cap, made of gores be the men’s skullcap?

According to Ilmari Manninen, men in Estonia used to wear a murumüts i.e. a sort of skullcap in summer [fig.62]. Not everybody in Estonia, for instance people in South Estonia and in coastal areas of Lake Peipsi, knew it but where it was worn (e.g. in North and West Estonia) it was combined of blue-red or red-black gores. This cap obviously comes from Scandinavia, most certainly of all from Norway [fig.63].

“…In Norway it has been worn since ‘such old times as it has been possible to observe the folk costumes’ up to the first half of the 19th century. In Finland the skullcaps were also spread all over the country.” 18.

The men’s cap made of six gores, closely following the shape of the head has also been known since the Middle Ages. The seams were usually covered with a cord or a narrow ribbon. The cap made of four gores (korsmyssa) was worn underneath the helmet in the 16th century. Hatters in towns made these caps, often using gores cut off from worn clothes. Caps of gores have also been used as death-wear with a better urban suit. A cap made of four blue gores (patalakki), decorated with a button or tuft on the crown [fig.64] was worn yet even in the middle of the 19th century. After that it slowly began to disappear. 19.

Manninen writes the following about the Estonian men’s summer caps made of wedge-like gores, “Although only old crones and no men wore these caps in Mihkli, they were still called ‘men’s wear’. At some places only herders wore these caps finally. In Simuna they used to say that only herders and dimwits wore them. At several places the cap was given to children when the grown-ups did not like it any more. Then these were mainly boys, seldom girls, who wore them. So, for example, in Kihnu they do not remember any adult wearing the cap, but boys wearing them are remembered.” 20.

This sort of a cap sewn of gores definitely was an example to a baby-bonnet for boys – the similarities are so obvious. The baptismal caps were more decorated, the ones for everyday wear were simpler.21.

Summing up

Although our expert on folk costumes, Reet Piiri thinks that no difference was made in baby bonnets for boys and girls in the continental part of Estonia 22. we may conclude on the basis of the two conserved bonnets that it sometimes still happened. The custom started to disappear towards the end of the 19th century or at the beginning of the 20th century. Then similar, much-ornamented caps for both sexes became popular. Lace and ribbons, at some places also embroidery were widely used – the more the better was the idea. The babies looked like cream-cakes in their baptismal caps and robes [fig.65]. Sometimes difference was made in colours – pink or light blue ribbons or embroidery – but the cut of the caps was the same [fig.58], [fig.59], [fig.60]. More often than not, the linen and woollen fabrics were replaced with silk, tulle and very thin batiste as well as various ribbons and lace obtained either from the peddlers at fairs or from the town shops. The new urban fashions ousted most of the old ones. Still, a few old ways survived longer, as shown in a lace bonnet of gores from Varbla, where the skullcap had been widely worn [fig.61].

Owing to the source material used in the work, comparisons and analysis of the bonnets, I became convinced that the caps from the collection of the Art Museum do have gender. The assumption that these two might have been baptismal bonnets seemed to be corroborated. The twins’ mother had been using her fabrics and colours discreetly and it is difficult to say whether the cap was meant for a boy or a girl. The gender differences were revealed only when analysing the cuts and comparing them with baby caps of the neighbouring countries.

The conservator’s work is time-consuming indeed, as the materials and structure of the objects are closely observed and studied. So, finally, they seemed to talk to me and make me feel the atmosphere of their time and in this case also the warmth of a mother working on the bonnet of the expected baby. I somehow seemed to feel that there was a mysterious energy in these caps that urged me on when I was writing this article.

MATERIALS:

22.20.19.18.6.

REFERENCES:

1. The Kristjan Raud House-Museum was opened as a branch-museum of the Estonian Art Museum in Nõmme, Tallinn in 1984. The artist had been living in this house from 1929 until his death on 19 May 1943. His daughter Helge Pihelga had actively participated in the creation of the museum and had donated most of the items for the display. When the house-museum closed its doors in 2008, the collection passed over to the Estonian Art Museum.

https://kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee/kunstikogud7kristjan-raua.majamuuseumi-kogu/

2. The twins’ father Jaan Raud made a not in the family bible, “/…. / Kristjan was born on 9 October at five o’clock in the night. Paul was born on 10 October at one o’clock in the night.” The time of the night are given at the Old Style that was in force in 1865. Lehti Viiroja. Kristjan Raud 1865-1943. Looming ja mõtteavaldused. Tallinn 1981, pp 11-14.

3. Lehti Viiroja. Kristjan Raud 1865-1943. Looming ja mõtteavaldused. Tallinn 1981, p 10-13.

4. Lehti Viiroja. Kristjan Raud 1865-1943. Looming ja mõtteavaldused. Tallinn 1981, p 12.

5. Gustav Teichmüller (1832-1888) was a German philosopher and historian of philosophy, working in Tartu, Estonia. https://et.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustav_Teichm%C3%BCller

The works of J. Klever and O. Hoffmann in G.Teichmüller’s collection had had an especially ‘awakening’ impression on both brothers. – Lehti Viiroja. Kristjan Raud 1865-1943. Looming ja mõtteavaldused. Tallinn 1981, p 11-14.

6. Eesti Entsüklopeedia 8. Tallinn 1995, p 47; https://et.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kristjan_Raud

7. Eesti Entsüklopeedia 8. Tallinn 1995, p 48; https://et.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Raud

8. Examination of the material was completed at the Kanut laboratory. The digital table-microscope Dino-Lite (digital microscope Dino-Lite Pro/Pro2 AM 4000/AD 4000 www.dino-lite.eu), stereomicroscope (Zeiss) with max enlargement 50x and for fibre analysis stereomicroscope Examet (Japan) with enlargement 50x-400x were used.

9. 0.5% liquor of the neutral wool detergent Hõbelõng (OÜ Flora, Estonia) was used for washing. This detergent preserves the original softness of the item even after several times of washing.

10. 100% natural silk crepeline (France)

11. The shapes of papier-mâché were made of pieces of paper and PVA-glue after bases had been made of sheet wadding (100% polyester) that was covered with plastic (polythene) to provide a smooth surface. The shapes were covered with six layers of paper mass that was removed from the base when it had dried and the shapes were given finishing touches to fit the objects. The shapes were covered with sheet wadding and stocking fabric.

12. The storing boxes were made of archive-preserving cardboard in the company OÜMaksing (Paberipood Zelluloos, at 38, Narva mnt (Road), Tallinn).

13. Talking to Viive Lehola, my kindred member who lives in Kihnu on 3 April 2018, I heard that the tradition was safe and sound today. It happened that at that time she was making a baby-girl bonnet for her granddaughter. It was, actually, already the third cap, the baby had grown out of the first ones. As there have been no boys in the family for several generations, she has not made any baby-boy’s cap. Besides, there is no need to sew caps for both sexes just in case, as the sex of the unborn baby is no secret today. But she could confirm that the cutting was dissimilar indeed.

14. Piiprell is a colourful tubal glass bead.

15. The colours of the bonnets were obviously not so bright in olden times but we do not have much information about it. The girl-baby bonnets on the island of Muhu were sewn of an oblong piece of fabric that reached from the forehead to the nape and two round-ended sides. Despite the dissimilar cut both bonnets are called baby-caps. Based on the talk with Mai Meriste, the curator of the Muhu Local History Museum in March and April 2018.

16. Ildiko Lehtinen, Pirkko Sihvo. Rahwaan puku. Museovirasto, Helsinki 2005, pp 102-103.

A rare piece of information that the burial cap followed the cut of the baptismal one also comes from Finland.

17. Ingrid Bergman (text), Anja Notini (photos). Rahvarõivad Rootsis. Rootsi Instituut. (Folk Costumes in Sweden. Swedish Institute), Helsing- borg 2002.

18. Ilmari Manninen. Eesti rahvariiete ajalugu. Eesti Rahva Muuseum, Tartu 2017, pp 11, 113-114.

It is interesting to note that in Norway the men’s cap has mostly been of red gores and bordered with blue or black edges. They were made of woollen fabric mostly.

19. Ildiko Lehtinen, Pirko Sihvo. Rahwaan puku. Museovirasto, Helsinki 2005, pp 207-208.

20. Ilmari Mannninen. Eesti rahvariiete ajalugu. Eesti Rahva Muuseum, Tartu, 2017, p 114.

21. Some of the decorations like tufts or buttons on the nape must have been quite uncomfortable for the baby to lie on. This supports the theory that certain decorations were used only in the bonnets for the rare festive occasions.

22. Reet Piiri. Suur mütsiraamat. Eesti kihelkondade peakatted. Tallinn 2017, p 11