FINDS IN THE PAARMA FARM SAUNA IN ALTJA – COULD THEY REALLY BE DRAWINGS BY WIIRALT, SAGRITS AND UUTMAA?

Autor:

Kristiina Ribelus, Maris Allik, Ülle Soosaar

Number:

Anno 2019/2020

Category:

Conservation

Finishing layers of the interior walls in the sauna at Paarma Farm, in Altja, North Estonia were opened in July 2018. The owner wanted the architect of the project, Siiri Nõva, to include a wallpaper conservator in the project to examine the wallpaper layers. So Kristiina Ribelius, who has been studying and restoring historical wallpaper since 2007 was invited. The idea to inspect the wallpaper was born thanks to the local legend about three well-known Estonian artists, who using available means on the cardboard of the sauna chamber, had been expressing their creative ideas when being in the sauna together. The owner expected to find drawings made by Richard Uutmaa, Richard Sagrits and Eduard Wiiralt.

Four layers of wallpaper and plasterboard underneath them were clean of scribbles. However, when sporadic probes were made on the wallpaper layer on the cardboard under the plasterboard many-coloured pencil-drawings appeared.

The repairs had to go on and so the cardboard strips were removed from the walls at the end of the summer. As wallpaper conservation was impossible in situ, the cardboard panels and fragments of the upper wallpaper layers were brought to the Conservation and Digitising Centre Kanut for restoration and conservation, as the owner wished to display them.

Further research and conservation at the Kanut was accomplished by the BA student Ülle Soosaar and supervised by paper conservator Maris Allik. For Soosaar it was also her second-year term paper at the department of heritage protection and conservation of the Estonian Academy of Art.

Paarma Farm in Altja

Fishing village Altja in the Lahemaa National Park was first recorded already in 1465. Today it offers an opportunity to see typical coastal farms dating from the late19th up to the early 20th century. viide1 ⁽¹⁾ [ill 1]

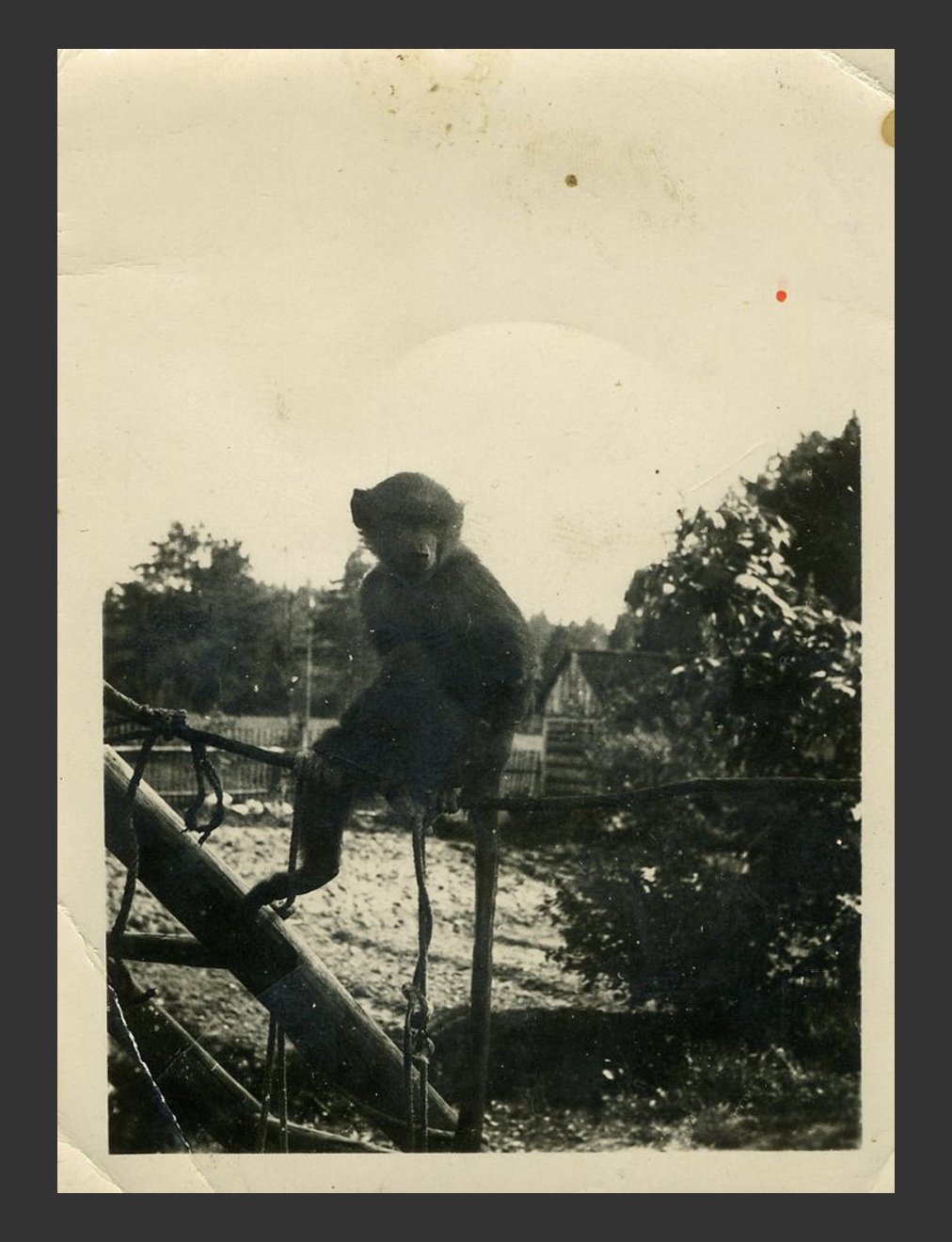

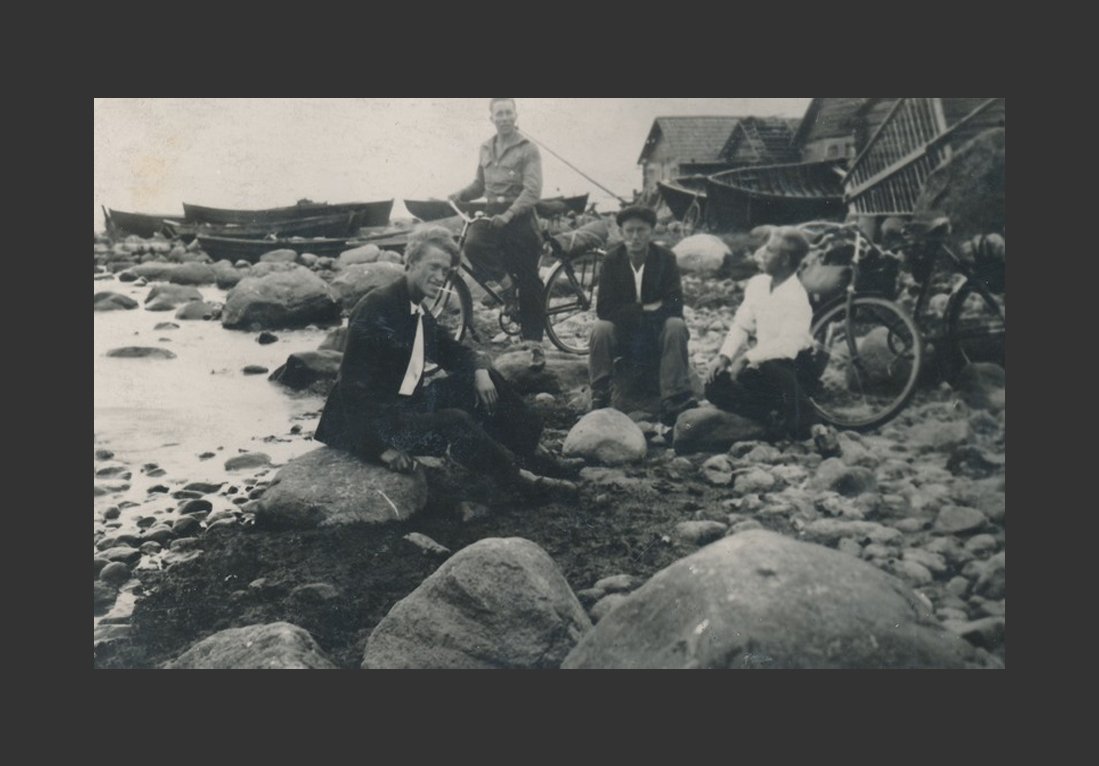

Paarma Farm was situated on the land that belonged to the Sagadi Manor: the owner’s summer-cottage, with wide fields and woods included, were on this land. At the beginning of the 20th century the farm belonged to Magnus Romman (1876-1970), a legendary captain and boat-builder. [ill 2], [ill 3] Romman, locally nicknamed Paarma Vunts (Paarma Whiskers), was an austere and frugal man [ill 4], who had seen many a land and sea in his life. He had been bringing exotic souvenirs from his many travels – once even a monkey, who the mistress of the house banished to live in the sauna. [ill 5]

The captain’s living-house built in 1926 had a large porch and was furnished in an elegant way. The family had many books and even an upright piano in one room. They all were fond of drawing and painting. The core of the farm on the Altja headland possessed several sheds, boat-sheds and a sauna in the vicinity. The small sauna on the bank of the Altja River consisted of an entrance-hall, bathroom (washing room) and a chamber-cum-cloakroom. And this is just the latter with which the legend about the drawings made by well-known painters is connected. viide2 ⁽²⁾[ill 6]

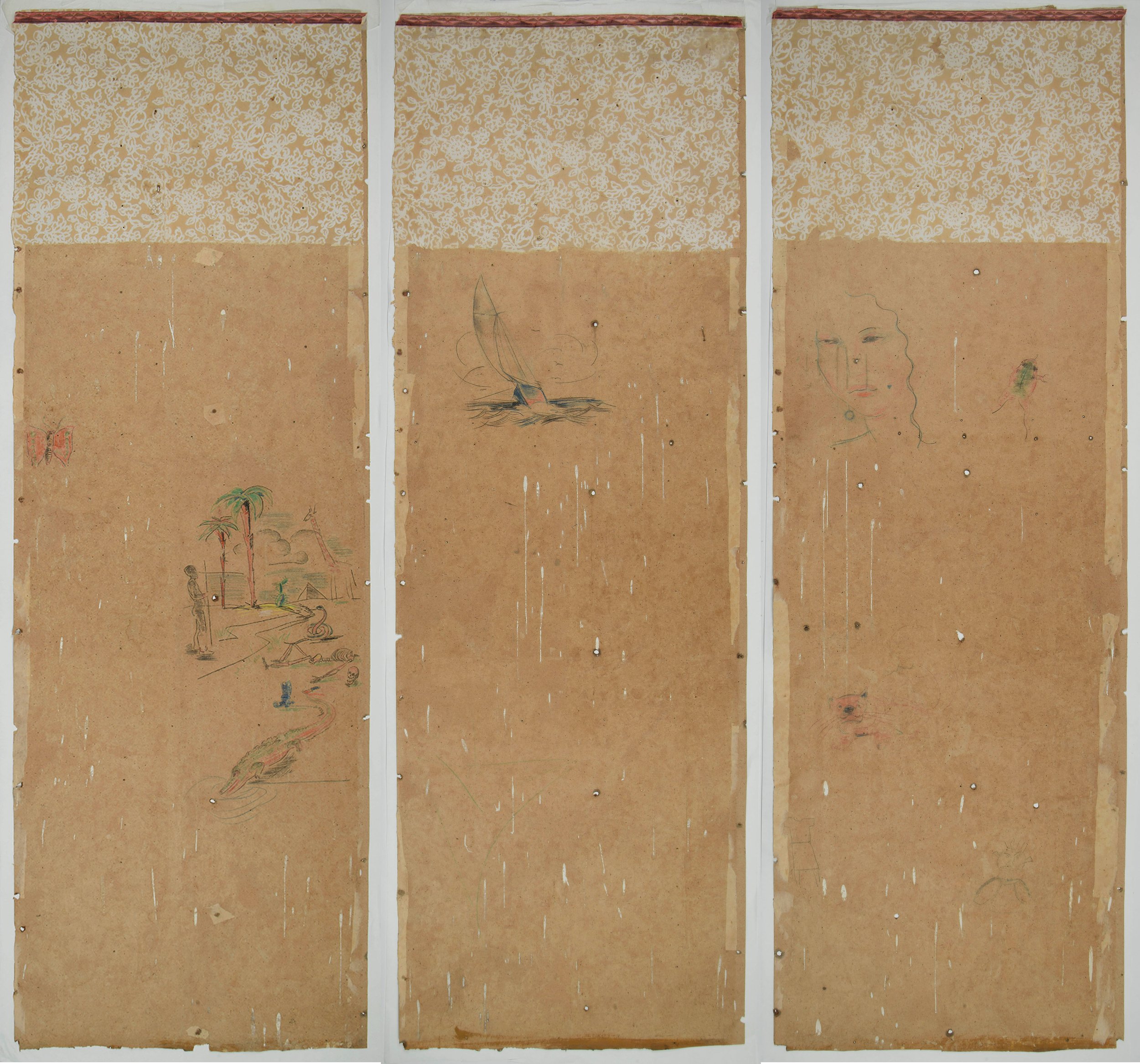

According to the legend the drawings of the three – Richard Sagrits, Richard Uutmaa and Eduard Wiiralt were on the eastern wall of the chamber-cum-cloakroom. It is known that Richard Uutmaa was well acquainted with the family and Richard Sagrits lived in the neighbouring village Karepa. [Ill 7] Eduard Wiiralt, who was acquainted with Uutmaa might have visited Altja with him. The drawings on the sauna wall might have been made in between 1930-1940. Why they were hidden was obviously the result of the captain’s wife Maali Katariina’s opinion that they were not suitable for the eyes of the couple’s young daughters. So, she had the walls covered with wallpaper. Later on some more layers of wallpaper were added. viide3 ⁽³⁾

Opening the paper layers and the first drawings

As already mentioned, the layers of wallpaper on the eastern wall of the Paarma Farm sauna were first studied in July 2018. Architect Siiri Nõva and the owner had started to open the wallpaper layers to find proof to the legend. They had to stop because the wallpaper was easily ripped and only small irregular areas opened up. [Ill 8], [ill 9] It was also thought that the drawings might be hidden in between the wallpaper layers and so specialists’ help might be needed. Thus, Kristiina Ribelus was engaged.

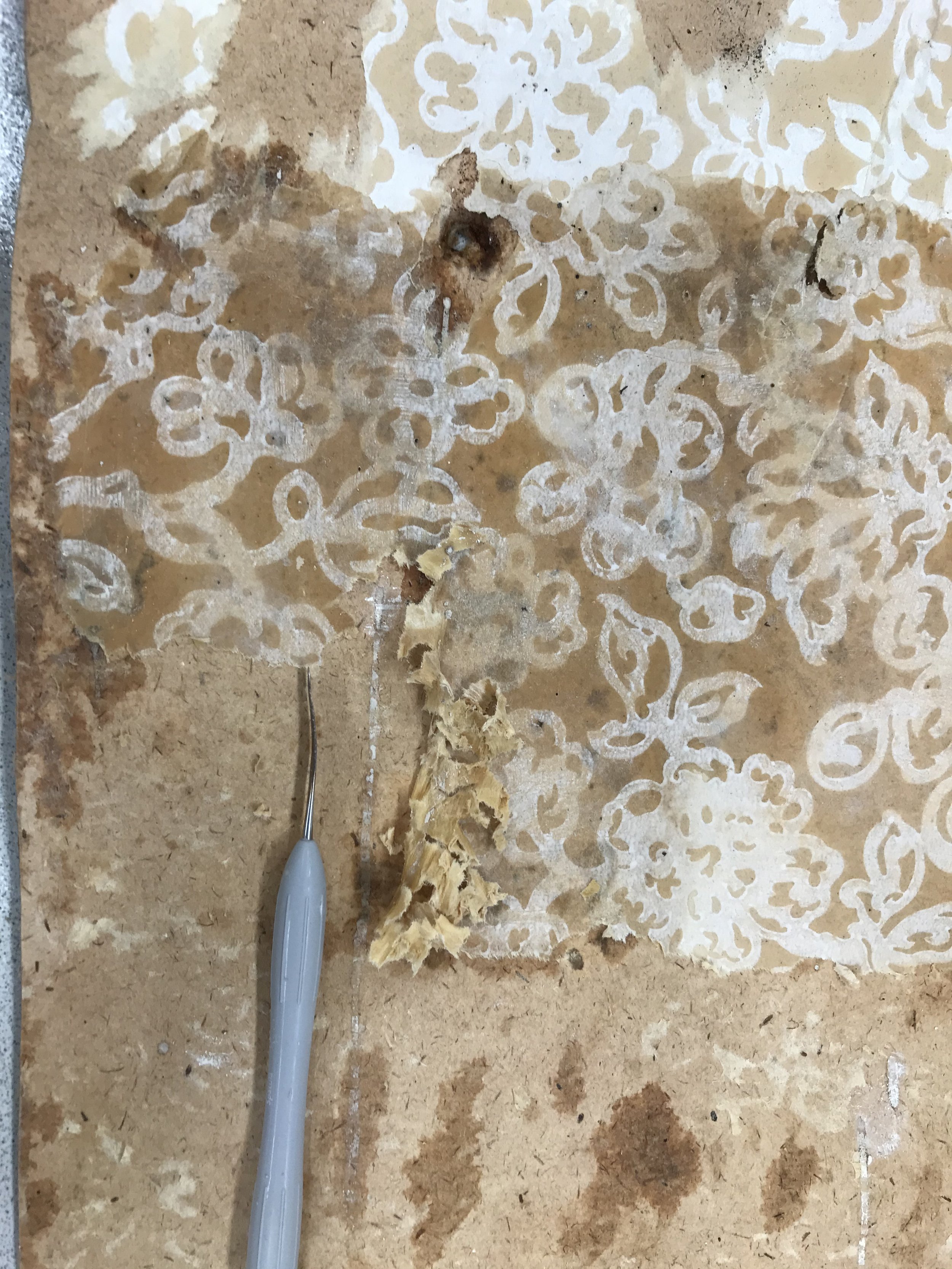

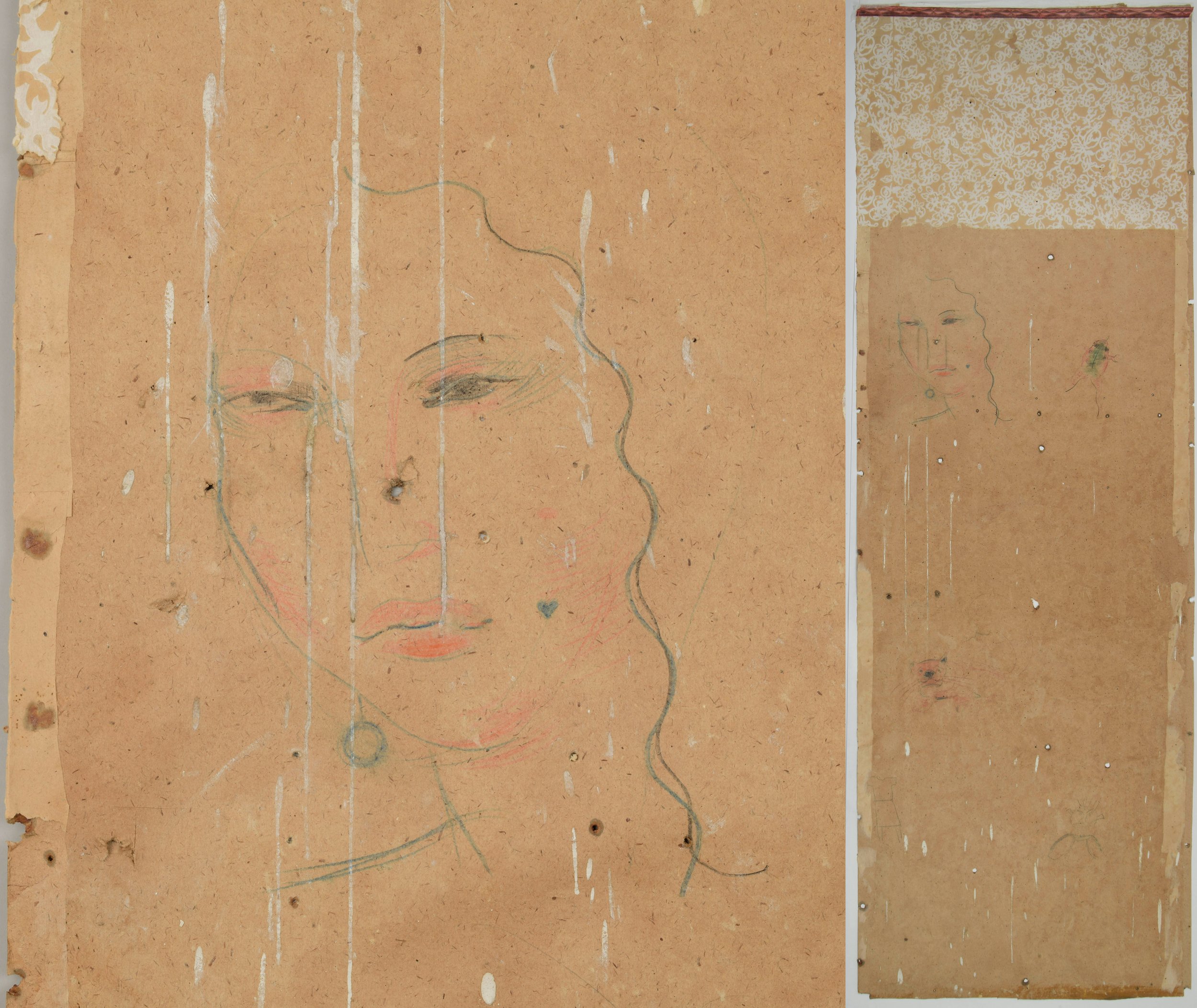

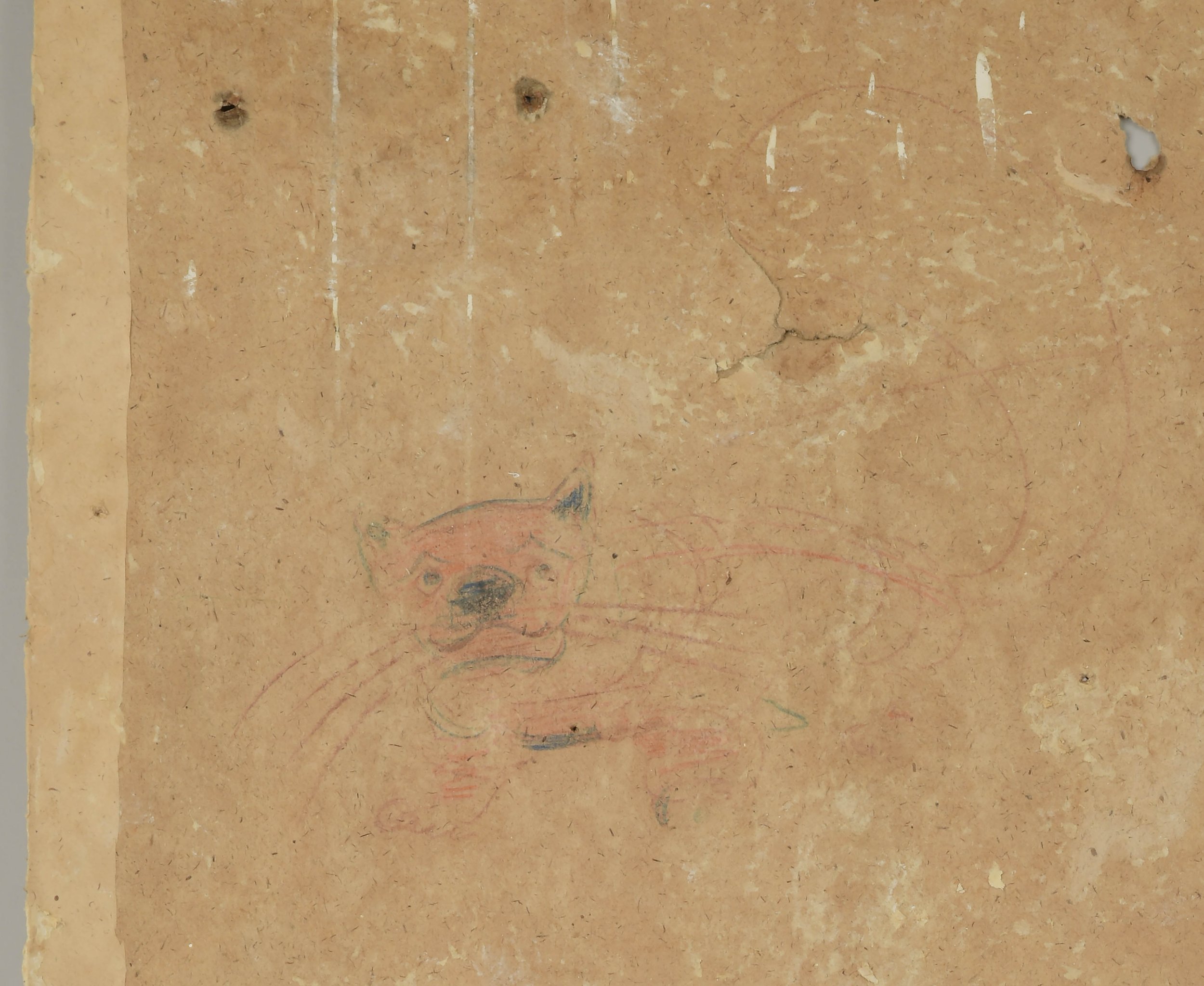

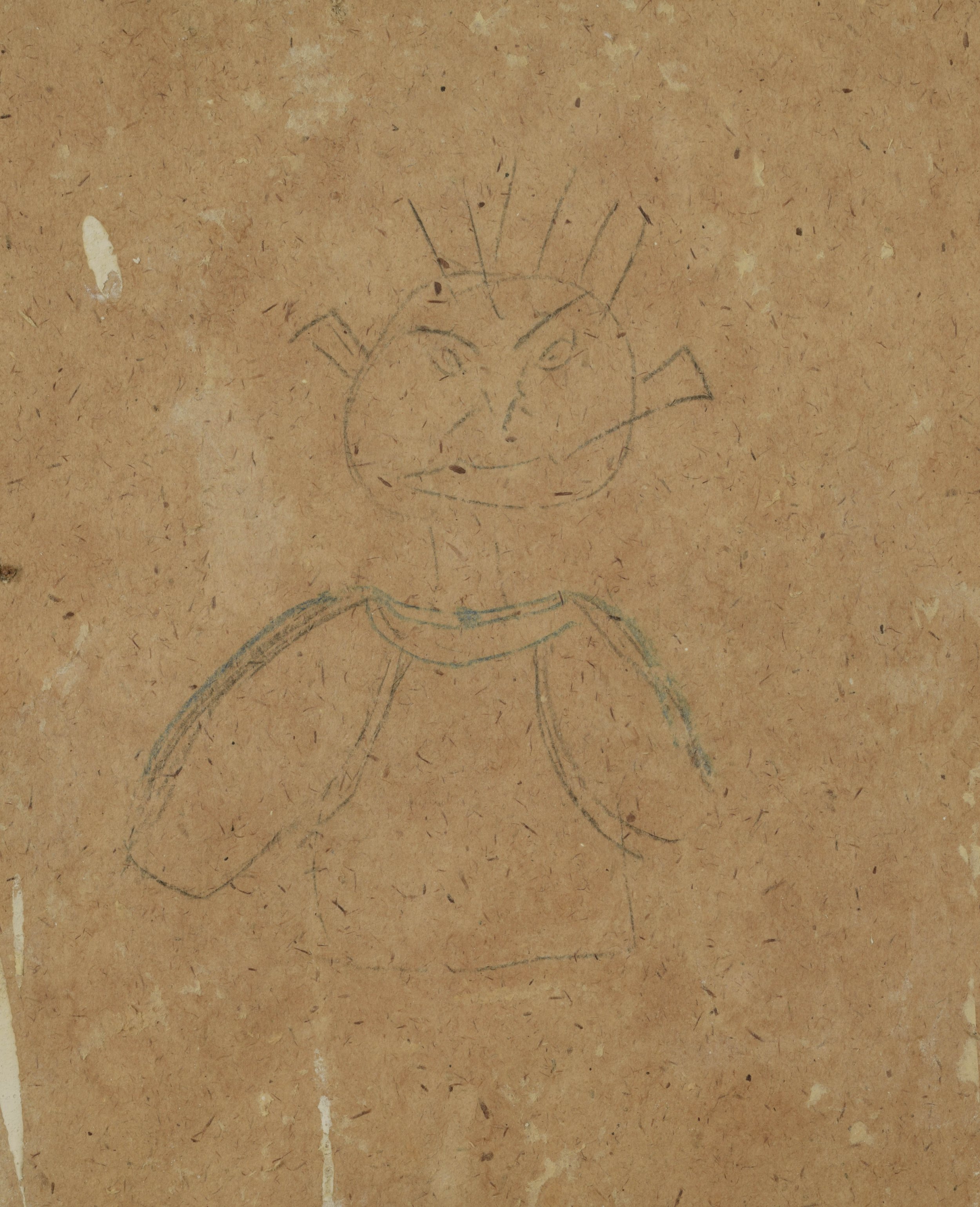

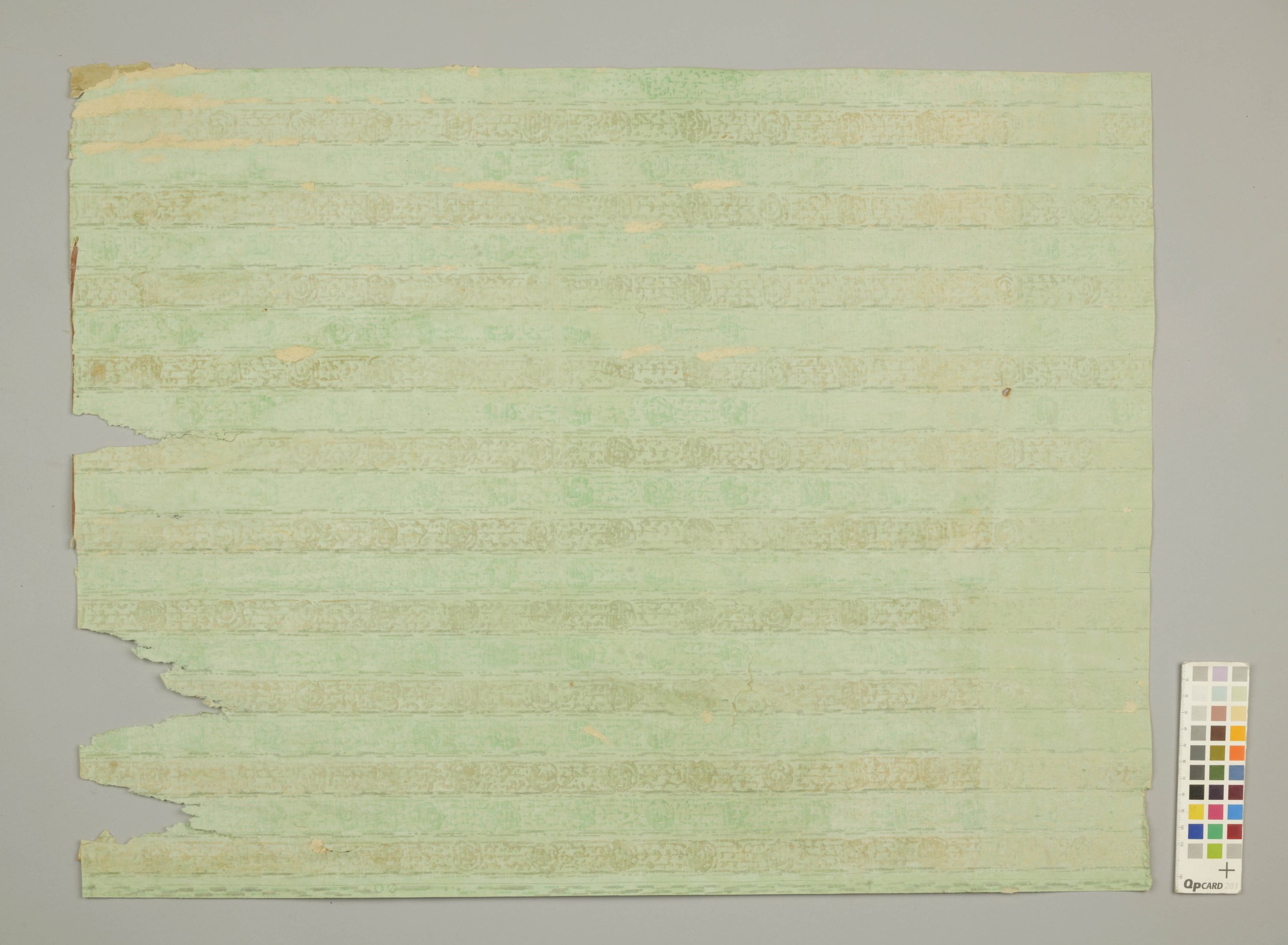

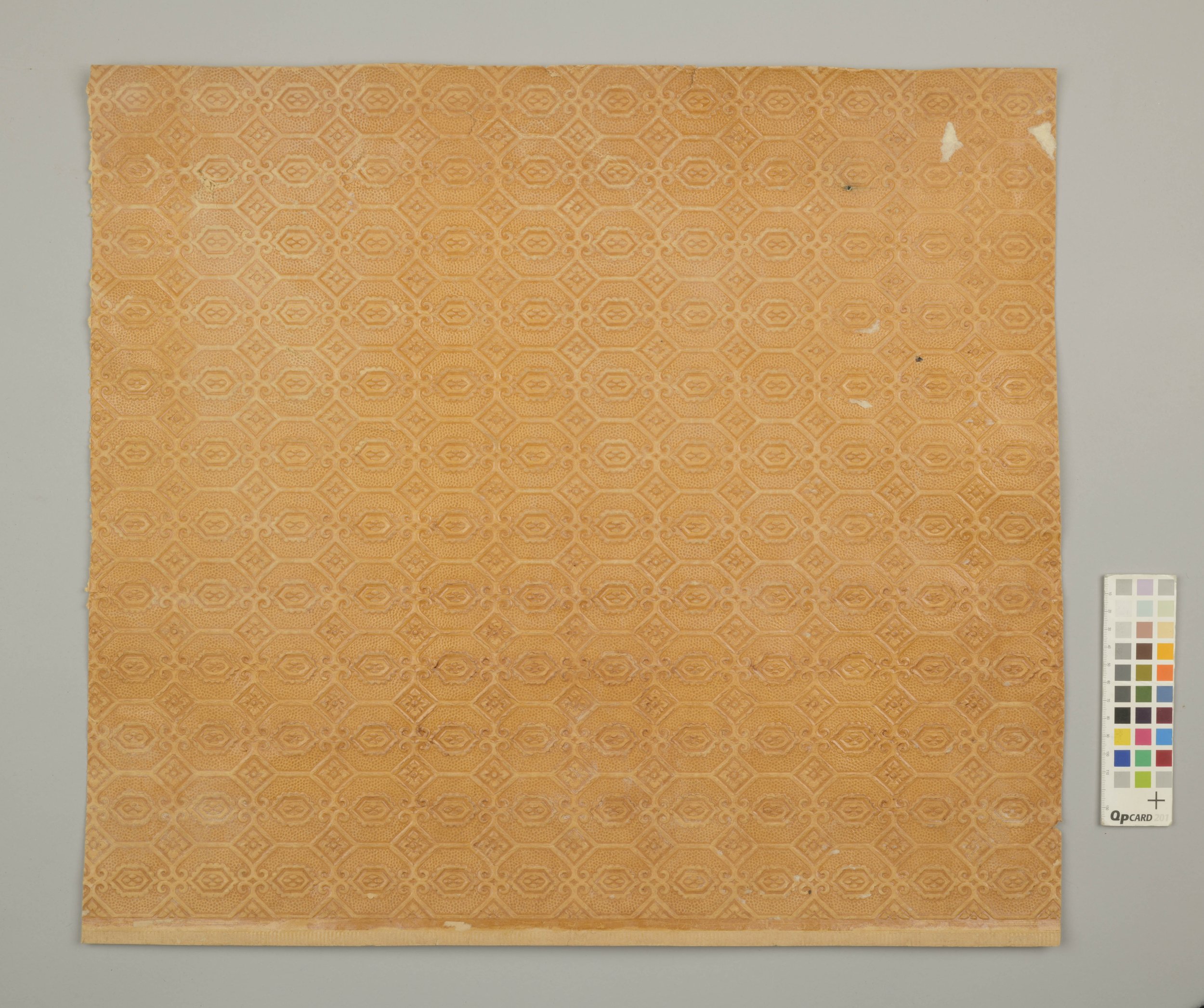

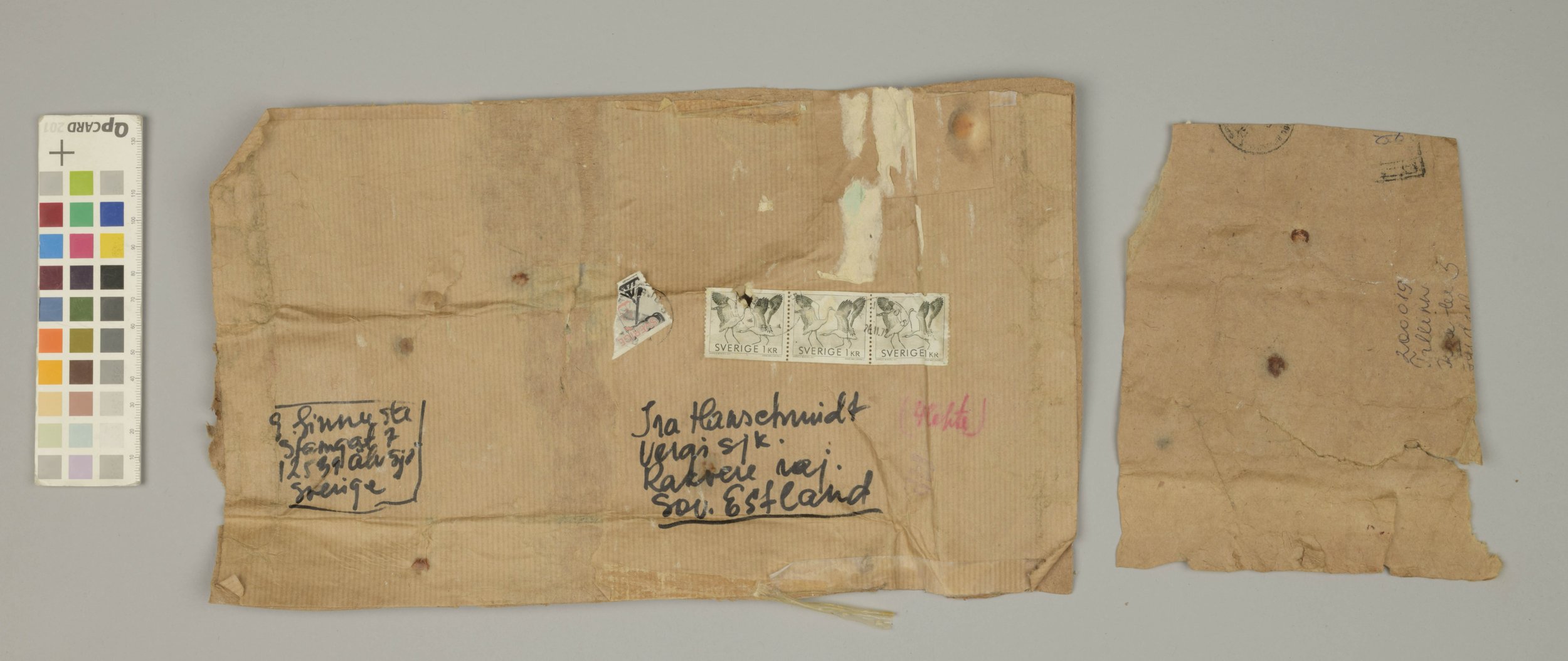

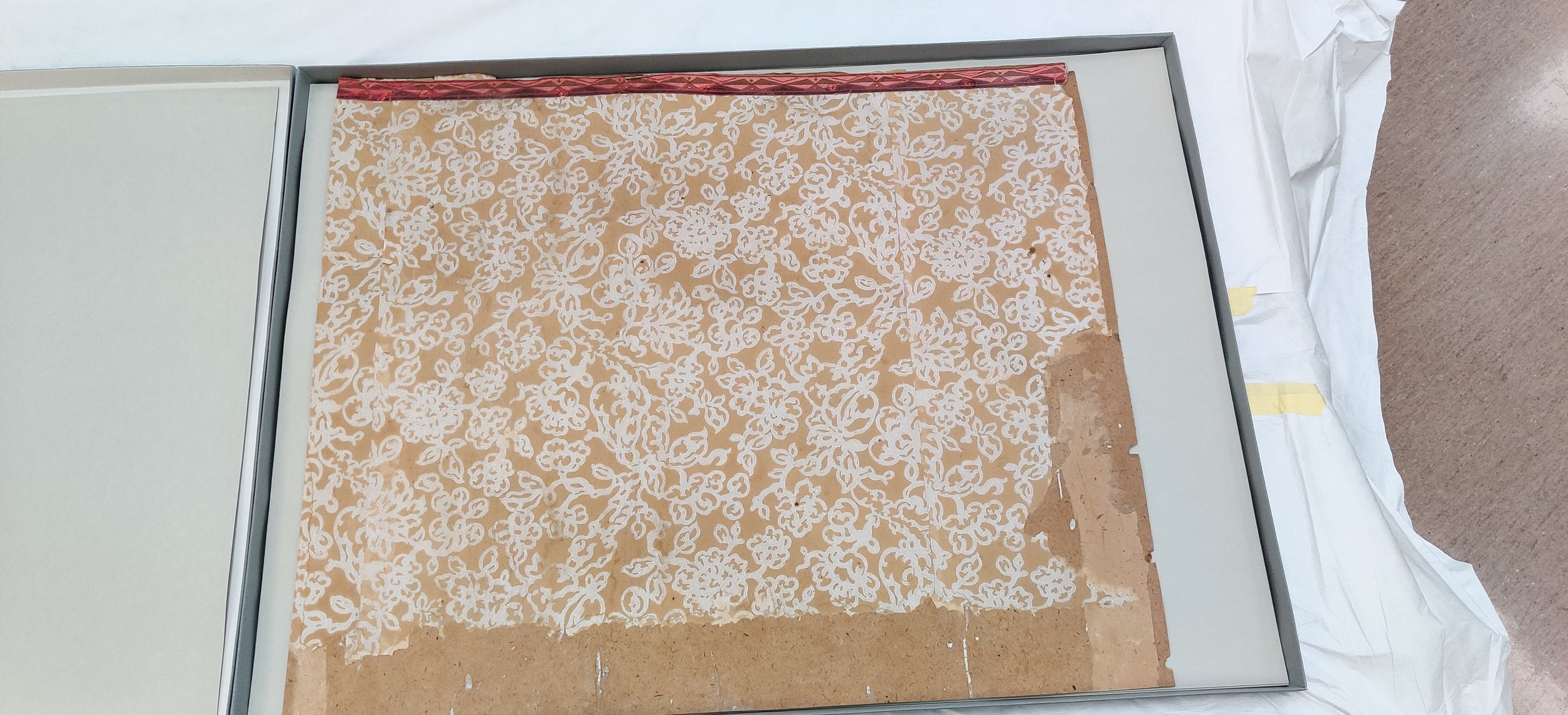

Next, they worked on separating the layers from each other, using Kärcher vapour-washer, local well water and mechanical means like a scalpel and a spatula. Processing the layers with hot vapour helps to separate them from each other more easily, as the paste yields and so bigger pieces of wallpaper can be removed without ripping them. First the upper wallpaper layers were opened and studied. Having ascertained that there were no drawings, the next layers were taken on. From the first four layers several pieces as wide as the strips and with repeated pattern were separated for further saving. [Ill 10] The wallpaper had been pasted on plasterboard dating from the 1970s. It was removed from the wall, as there were no drawings on it either. The envelope preserved for keeping [ill 11] and other bits and pieces of paper that had been used for smoothing the joints of paper strips were found on the plasterboard. Under the plasterboard was white-patterned wallpaper pasted on five panels of cardboard. This wallpaper [ill 12] did not bear any drawings either. Searching traces of drawing the wallpaper was opened piece by piece and some lines did appear. [ill 13] After that the area under drawings was opened to see the whole [ill 14] and, indeed, four separate pictures were discovered. They were a portrait of a woman, a frog and a sailing boat out at the sea and, also, an exotic landscape with a pyramid, giraffe, aborigine, crocodile and skeleton. [ill 15], [ill 16], [ill 17] All the four pictures were at different height that suggested the authors’ standing and sitting positions. [ill 18]

As the vapour-washer broke when working, it became impossible to open more layers and find more drawings. It was also a problem what to do with them. It was rather staggering that the legend seemed to be a true story. The white-patterned wallpaper was considered worth preserving in one pattern mode for the would-be report on the work. Unfortunately, however, it was not possible to remove this wallpaper layer entirely even with the help of hot vapour.

Now the conservation concept had to be seriously contemplated. Should the cardboard with the drawings be preserved where it had been found? Or should it be removed from the wall for conservation and archive storing? Or should the pictures be cut out of cardboard and framed? What was the very best way?

As the choice was complicated, it was decided to consult other conservators and some art historians. Hilkka Hiiop, conservator and tutor at the restoration school of the Estonian Academy of Art, was sure that the drawings had a considerable local significance and they should be preserved, where they were found.

The repairs had to go on and the moisture-damaged pieces of cardboard became a disturbing issue. By the end of the summer the cardboard strips had been removed from the wall. Their succession on the wall was marked on the reverse side from left to right, from one to five and they were packed together with the examples of wallpaper to be sent to the Kanut.

The objective of the conservation and processes accomplished at the Kanut

The primary objective was the conservation of the finishing layers of the interior, preservation of the historical material and restoring its aesthetic appearance. The correct general look is especially important if the drawings might be displayed in the future. The role of conservation appears in preserving the materials as long as possible, so that they could be used for historical research.

Five cardboard strips, three of them with drawings in crayons were brought to the Kanut for research and conservation. In addition, there were four different fragments of wallpaper layers, already separated from each other and a piece of an envelope that had been used as spoilage underneath wallpaper.

All the above-mentioned preserves were in satisfactory condition: the paper had some mechanical damage like rips in the upper and lower parts of the strips, holes from fixing nails and deformations. In order to assess the rise in the paper acidity caused by ageing, the pH-value was tested on several of them. On the surface of the cardboard the pH showed 4.2-4.5 and inside the cardboard 4.0-3.9. In the reverse surface of the white wallpaper the pH was 4.3, on the front side 5.8. The highest indicator (decreasing acidity) on the surface of the wallpaper could be caused by the influence of the printing ink's alkaline reaction on paper. This white-patterned wallpaper had been lighter initially and yellowed when ageing.

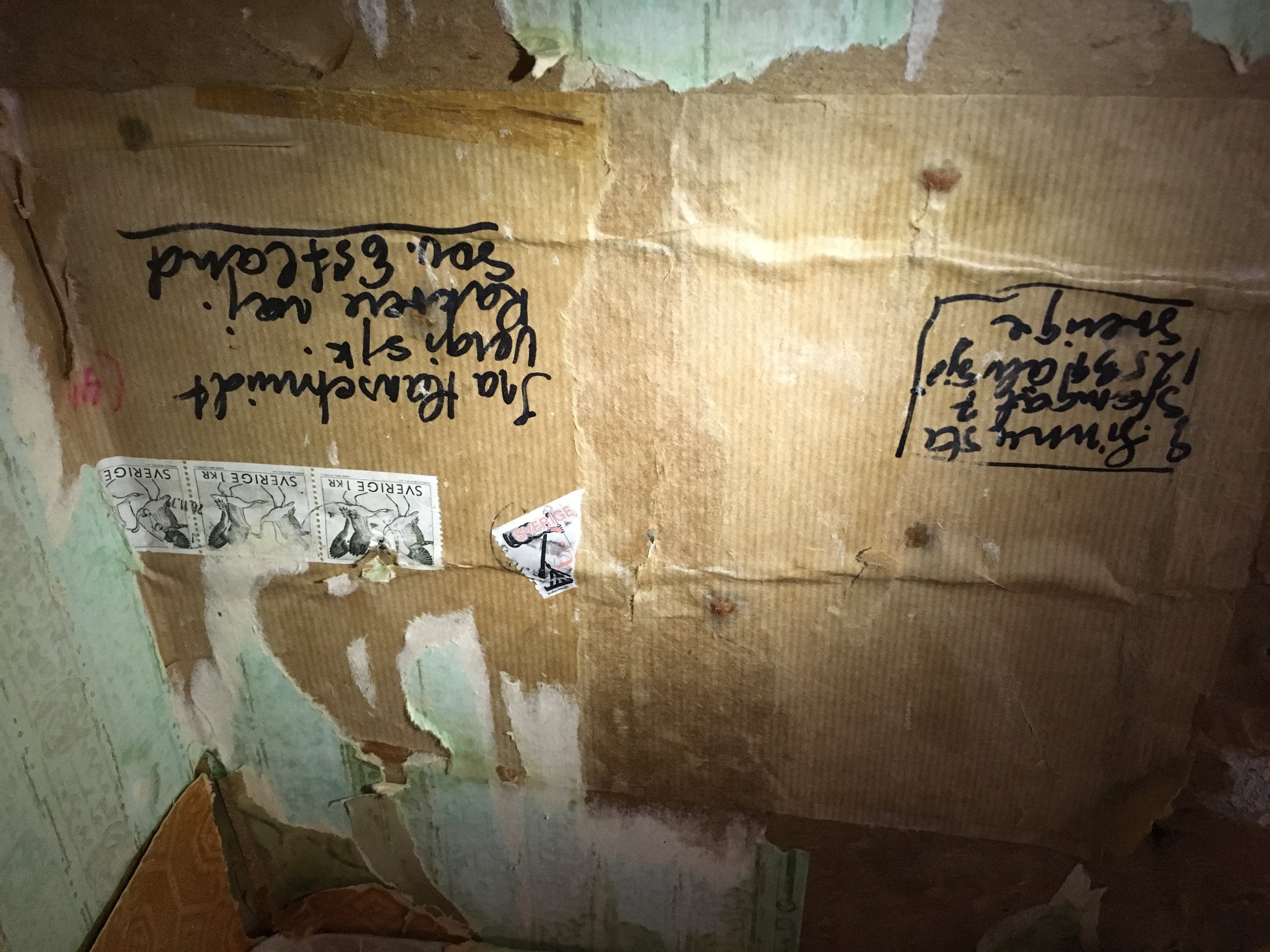

The succession of the wallpaper layers on the wall was not in accordance with the age of wallpaper. The thicker wallpaper has been dated either to the end of the 19th or the beginning of the 20th century, but on the wall it had been used upon the newer wallpaper. They say that these older rolls of wallpaper had been found in the attic of the house and used much later than the wallpaper was produced. The same type of wallpaper although with a different pattern has been used also in papering the walls of one room in the living-house. This kind of wallpaper, the pattern of which imitates woodwork has generally been used for covering the lower wall panels or in rooms like kitchens and bathrooms that require a more resistant wall covering. The later-day wallpaper is soviet-time mass production. Although these later wallpaper strips were pasted so that the edge of the previous one was covered by that of the next, it was not possible to find any information on the producer or time on the borders. It was interesting to discover that the design of all the wallpaper from the sauna is characteristic of its time’s fashion – a more-or-less stylised flower impression. The spoilage used to even up the ground material was also quite noteworthy, especially the envelope that still had the receiver’s and sender’s addresses on it. Studying the genetic data and interviewing the owner, direct contacts were established.

The cardboard had been cleansed of heavier dirt (sand, sawdust and cobwebs) already when it was being removed from the walls. The cardboard strips brought to the Kanut did not need further dry cleaning. The surfaces were wiped with micro-fibre duster and after that it became possible to start searching for the possible drawings underneath the white-patterned wallpaper. As said before, it was difficult to remove the wallpaper without harming the cardboard under it and a new way had to be thought out.

Gentle finger-touches led to spots where wallpaper was already a little loose. A metal spatula was considered suitable to remove the fragile wallpaper. This, however, did not allow observing the entire surface underneath and so it was decided to check all the cardboard strips after wetting them. The wallpaper layer was dampened with 50% ethanol aqueous solution. Dampening made the paper more transparent and – lo and behold, the contours of a drawing had become visible, whereas the red crayon was more clearly seen than the black pencil line. The suspected dark vertical lines, however, were but paint drops that had dripped on the paper when the ceiling was painted.

The wallpaper was separated from the cardboard with drawing with the help of dampening it. The layers can be removed from each other when gluing in between them is weakened. Wheat-meal and starch pastes get softer when dampened but the older and thicker rye-meal paste is more difficult to remove. Fish-glues submit better to warm water. The process is more complicated with synthetic glues, as even using organic solutions might not always give good results. viide4 ⁽⁴⁾, viide5 ⁽⁵⁾

A rather weak dampening was applied for the start, but it did not affect the gluing. A stronger dampening with 50% ethanol aqueous solution was tried in order to make wetting and solution evaporation quicker and avoid tide lines. Unfortunately, this did not give the expected result either. Dampening the surface with methyl cellulose (MC) gel followed, but the glue was still resistant and complicated to remove. Finally, the wetted wallpaper had to be peeled off mechanically. It was tried to soak it in a warm water-bath as well, hoping to discover whether fish-glue might have been used. We cut a piece out of the drawing-free cardboard and used that for testing, but still achieved nothing.

The hindrance at separating the wallpaper layers may have various reasons like, for instance, the cumulative effect on the surface of the used glue and cardboard – tight chemical connection between the two materials that do not yield to the usual wetting process.

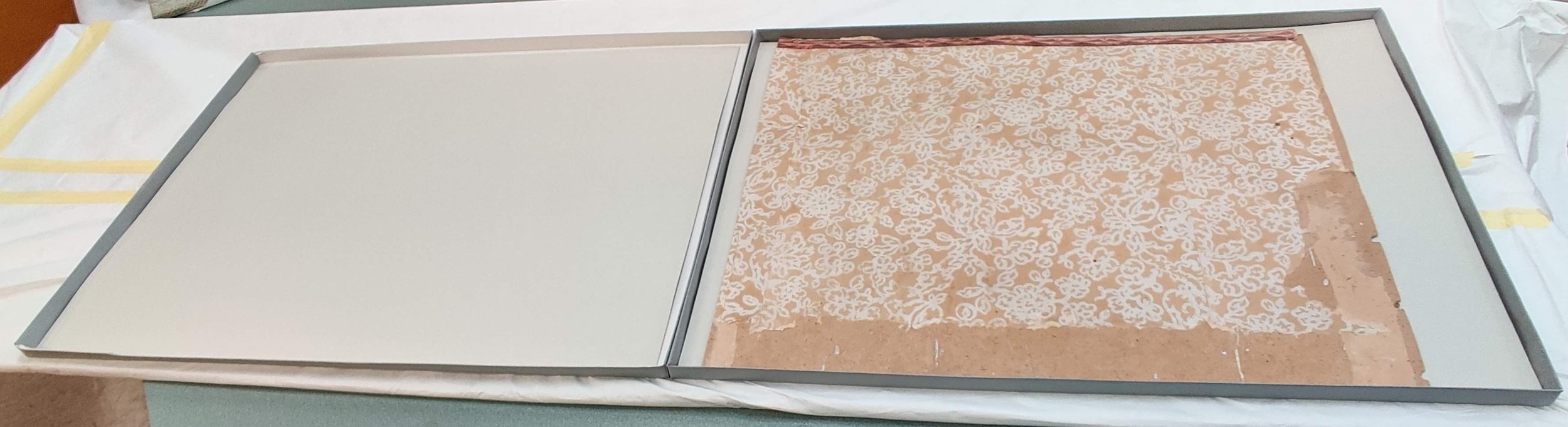

Finally, it was decided to use the Kärcher vapour-washer at the Kanut, too. Vapour emerging at higher temperature and under harder pressure was definitely the best method, as it was fast and allowed quick performance. Hot vapour processing was locally applied: moving from one ca10x20cm area [ill 19] to the next. The wallpaper layer became dampened at once and it was possible to remove it quickly before moisture reached the cardboard surface. [ill 20] The wallpaper layer removed in this way could not be preserved, as it came off the cardboard in a viscous pulp.

Generally, it is not recommended to use temperatures over 45°C when processing paper materials, especially in case of longer processing, as it may accelerate decomposition of cellulose fibres. The accelerating effect of temperature can be used when its influence is weaker than that of alternative methods (like long-time wetting procession, chemical or mechanical interference) and the object requires interference (like disassembling historical wallpaper packets for research purposes). Application of vapour on horizontal surfaces requires concentration to prevent condense water from pooling on the object’s surface. Uneven dampening of damaged and soiled paper may cause tide lines. To avoid tide lines on the processed area, filter paper should be used. The unpleasant rather cutting noise that the working vapour-washer produces requires earmuffs for the operator.

When wallpaper had been removed the remaining paper fragments were cleansed off the cardboard, using cotton swabs dampened in a weak methyl-cellulose (MC) aqueous solution (1-3%) and a metal spatula. The solution simultaneously fixed loose fibres in the surface layer of the cardboard. [ill 21] Rents on the borders were dampened with the same solution and repaired locally with 20g/cm2 Japanese paper, for glue starch paste was used. Lime-paint trickles were preserved as remnants from ‘the object’s history’, but splashes were removed from the drawings with methyl-cellulose solution to retain the visual entity. Still, it was not finished in excessive thoroughness, as the main aim was keeping an historical picture real.

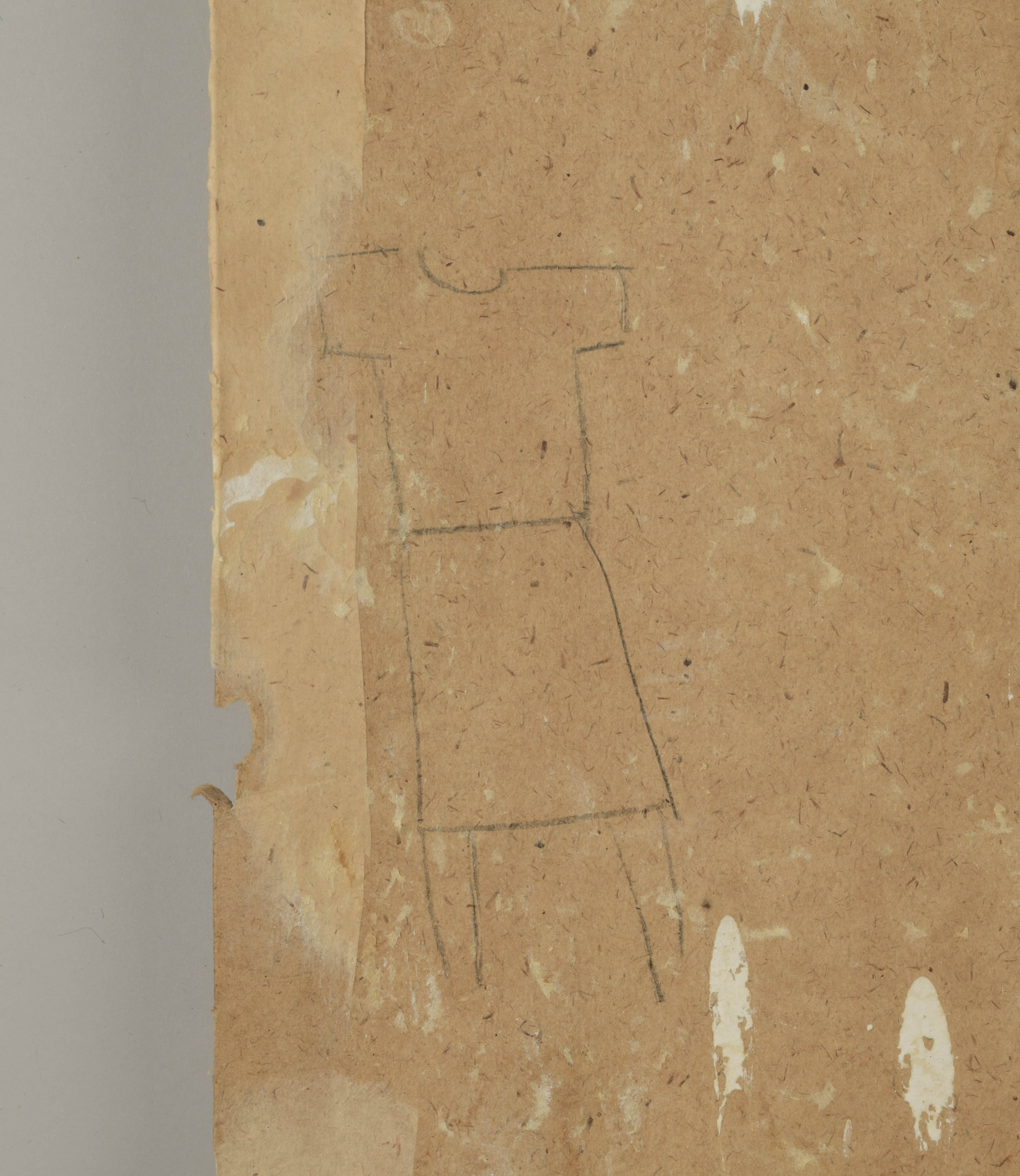

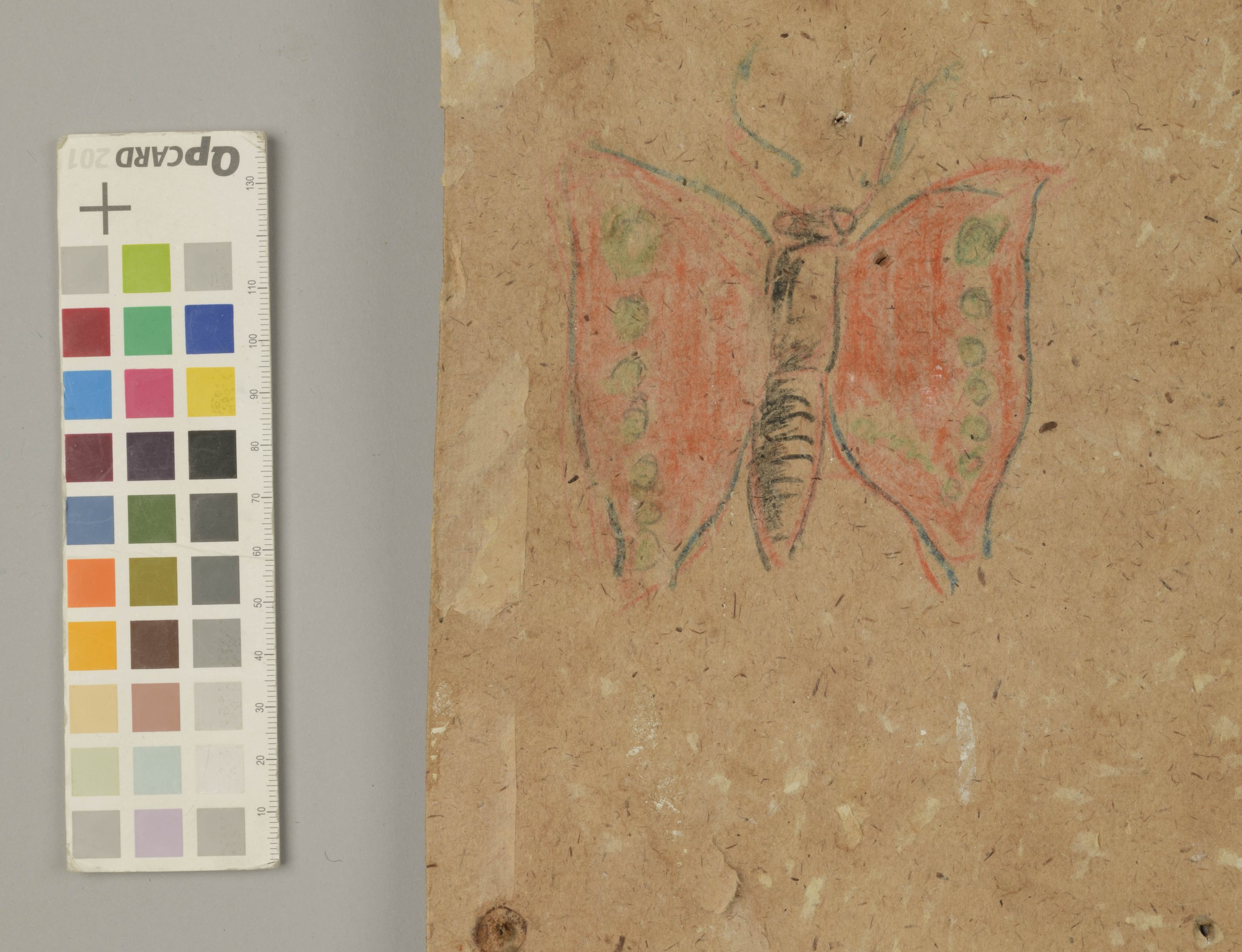

In addition to the earlier discovered drawings, images of an animal and a butterfly were discovered on the strips. On one of them two plain black-lined matchstick figures were found, with a few haphazard pencil-lines in the lower part. It is obviously impossible to ascertain, whether artists or children of the house created these figures. [ill 22], [ill 23], [ill 24], [ill 25], [ill 26], [ill 27],[ill 28] For a better visual impression a 52cm-wide wallpaper piece with its border intact was retained in the upper part.

The pencil drawings under the wallpaper layers had preserved well – the lines were whole and the colours bright. Tiina Abel, an art historian and lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Art was consulted about the authorship of the drawings. She thought the drawings were professional indeed, but was rather sceptical about the participation of Eduard Wiiralt (1898-1954), as he was older than the other two. Besides that, Wiiralt left Estonia first in 1925 and came back only in 1939-1940. Before Wiiralt’s departure Sagrits (1910-1968) and Uutmaa (1905-1977) were professionally too young to be friends with Wiiralt, although dating the drawings to 1930-1940 seems all right.

Summary

As examples all the pieces of wallpaper that covered the plasterboard in the Paarma Farm sauna will be retained. The same goes for the fragment of the white-patterned wallpaper, underneath which the drawings had been. The examples were packed in an archive-lasting cardboard box. [ill 29], [ill 30], [ill 31], [ill 32], [ill 33], [ill 34], [ill 35] Of the five strips of cardboard the three with drawings were conserved. The strips were cleansed off the wallpaper layer covering them and the drawings were cleaned of plaster splashes, whereas the rest of the cardboard surface was only provisionally cleaned of the plaster drops. Deformation was repaired only in the areas with drawings, whereas the nail holes were not touched. A 52cm-wide piece together with border was retained in the upper part of every strip. The cardboard strips were stretched in local press for two-to-three months. [ill 36]

Possible ways for preserving and displaying the drawings

There are several ways to preserve and display the cardboard strips with drawings, beginning with storing them in a museum up to framing them separately. This kind of material with local significance should rather be displayed than stored in a (museum) storage depository. During the discussions between specialists of the Kanut, the interior designer and the owner two main issues seemed to become eminent – the format of the drawings and the possible place of exhibition.

The following was considered:

Single drawings displayed separately in suitable format and framed. Unfortunately, this would destroy the originality of the object.

Displaying the digital copies and storing the originals in wrappers. The advantage of this choice would give a further opportunity to format the drawings in any described way. Architect Siiri Nõva suggested that the original drawings should be conserved and the digital copies framed and displayed on the wall of the sauna chamber, where they had been found. The originals could be stored in the main building of the farm in this case.

Displaying the cardboard strips in their original way as a wall. Cutting the strips up would wreck the story, the entity and the context (the placing of the drawings shows who of the men was sitting and who standing).

Displaying the digital copies of the cardboard strips on heavy-duty material that could last moisture and variegating temperatures in their original place – the sauna.

Displaying them in some memory institution or a near-by community centre, like Richard Sagrits’s house-museum or the Altja Inn. It requires the institution and, naturally, the owner’s consent, and a much more thorough research of the story in context of local history and community. SA Virumaa Muuseumid (the Foundation Virumaa Museums) would be happy to display the drawings in Richard Sagrits’s house-museum.

There might appear a possibility to display the conserved cardboard strips as one entity in their original succession in the dwelling of the farm after the building is reconstructed.

When the format is a compact panel, it is possible to frame it and display it on the wall. It could also be formed as a sliding wall and used as a room-divider. The interior designer and the subscriber considered a sliding wall in some of the buildings would do. In this case the conserved cardboard strips could be backed on a bigger canvas and stretched on a base frame. The wallpaper piece left in the upper part of the cardboard strips would impress as a joining historical element.

In addition to finding the best solution for displaying, it is also essential to create the best possible conditions for storing and constant observation of these conditions stability. The room has to have stabile temperature (between 18-22°C), air humidity (RH 35-45%) and good ventilation. The object needs protection from direct sunlight. The UV-component-free lamps would protect the colours of the drawings from fading.

Further conservation solutions would depend on the owner’s decisions and prospects about storing and displaying the object.

The present article was presented to draw attention at the existence of the drawings and in hope that a would-be researcher on Richard Sagrits, Richard Uutmaa or Eduard Wiiralt’s life and work might also visit the sauna in Altja and confirm the possibility of the drawings as their work. viide6 ⁽⁶⁾

Viited

Tarvel, Enn. Altja. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1981 ↩︎

Conversation with the owner of Paarma farm Külli Kuivaste in Altja, 27.12.2019 ↩︎

The same conversation in Altja on 27.12. 2019 ↩︎

Cardboard and glues from the early 20th century up to the 1950 [https://majatohter.ee/tooted/ehitus/pingupapp/pingupapp/(https://majatohter.ee/tooted/ehitus/pingupapp/pingupapp/) ↩︎

Tamm, Kadri. Käsitsi trükitud tapeedid (Handprinted wallpaper) – Äripäev, no38. Sisustaja, November 2012. (the article contains an interview with Kristiina Ribelus about her work at the Käsmu Church. https://static-pdf.aripaev.ee/pmv2159u2h6gPg44Dmtyr-oG2hc.pdf ↩︎

Ribelus, Kristiina. Altja saunamaja viimistluskihtidest (About the finishing wallpaper layers on the walls of Altja sauna). 01.10.2019. Report on the conservation. (Author’s property) ↩︎