PEEPING AT THE DAWN OF ESTONIAN PHOTOGRAPHY. MAPPING ESTONIAN DAGUERREOTYPES

Autor:

Kadi Sikka

Year:

Anno 2015

Category:

Research

The first more widely spread photographic procedure – the daguerreotype – was introduced to the public in Paris in 1839. The present article deals with one of the most revolutionary events in the photographic history and, in addition, employing the method in Estonia, including the project of mapping the daguerreotypes in Estonia in 2015.

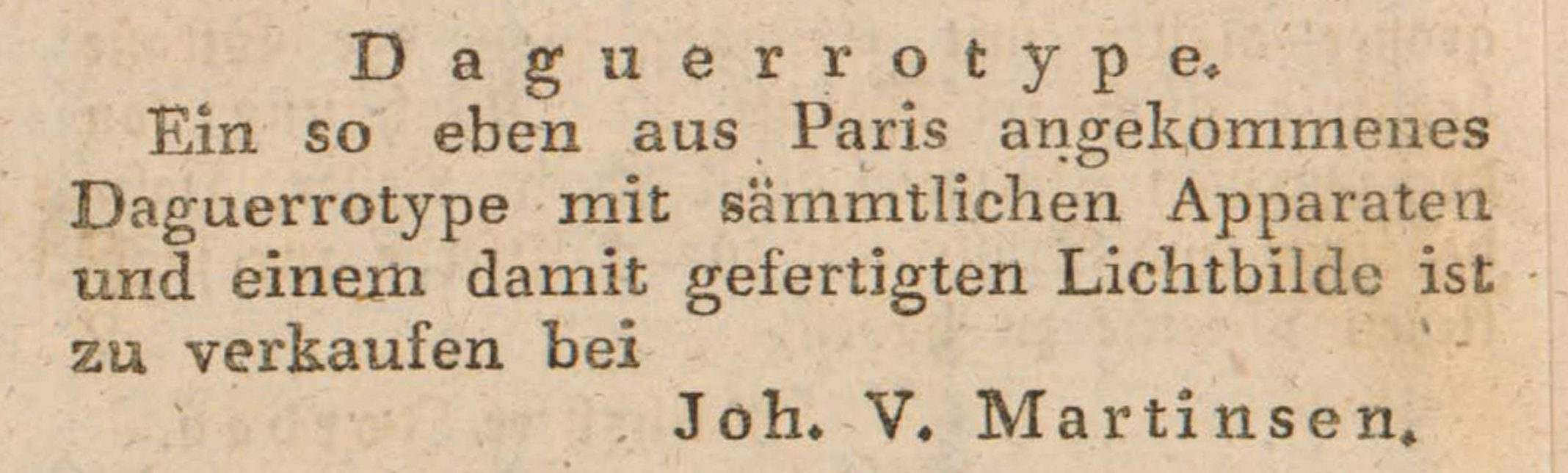

The news about the invention of daguerreotypy reached the countries around the Baltic Sea surprisingly fast. The press of the western provinces in the Russian Empire published information about the new photography method in 1839 and European newspapers brought the news to Estonia at the beginning of the same year. The first advertisement connecting Estonia with the new invention was published in the newspaper Revalsche wöchentliche Nachrichten on the occasion of merchant Johann Martinsen of Tallinn selling a daguerreotype camera in August 1840. The first confirmed records on travelling photographers date back to 21 June 1843, when Benno Lipschütz and Babtista Tensi who had come from St Petersburg, announced that they were making daguerreotype portraits in Tallinn. In the 1840s to ‘50s photographing became quite common in Estonia and every year some travelling photographers visited Tallinn and Tartu. In these towns about twenty photographers worked at the height of daguerreotypy-period between 1840-1854. In addition to Lipschütz and Tensi, Carl Borchardt, Theodor Gerwien, Georg Kleinschneck, Carl Neupert, Wilhelm Schönfeldt and some others advertised in local newspapers.

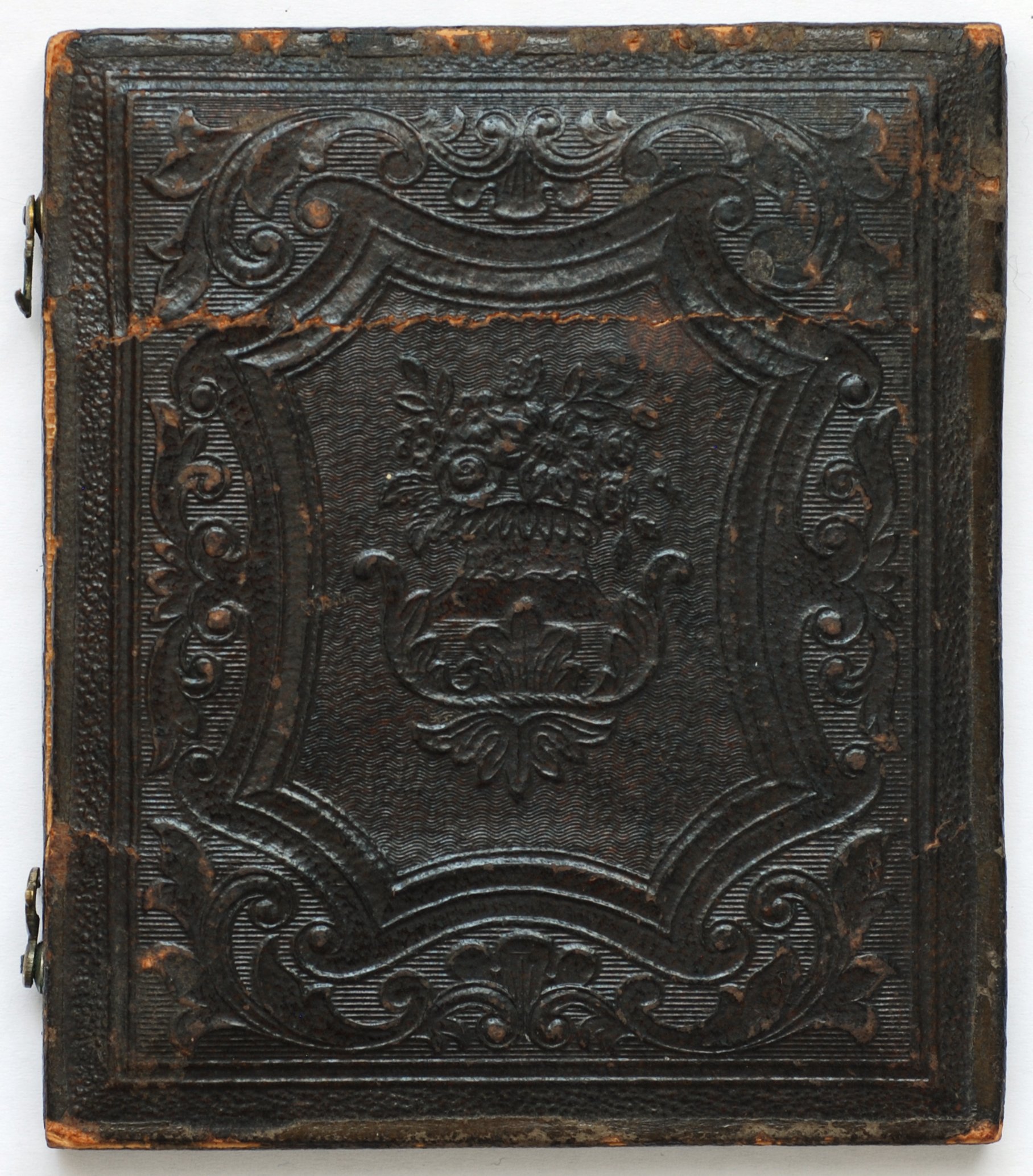

However, despite the active photographing work of travelling photographers, only 22 daguerreotypes have preserved in Estonian collections. As the majority of the travelling photographers’ clients were Baltic Germans, most of the daguerreotypes made in Estonia must either have perished or taken abroad.

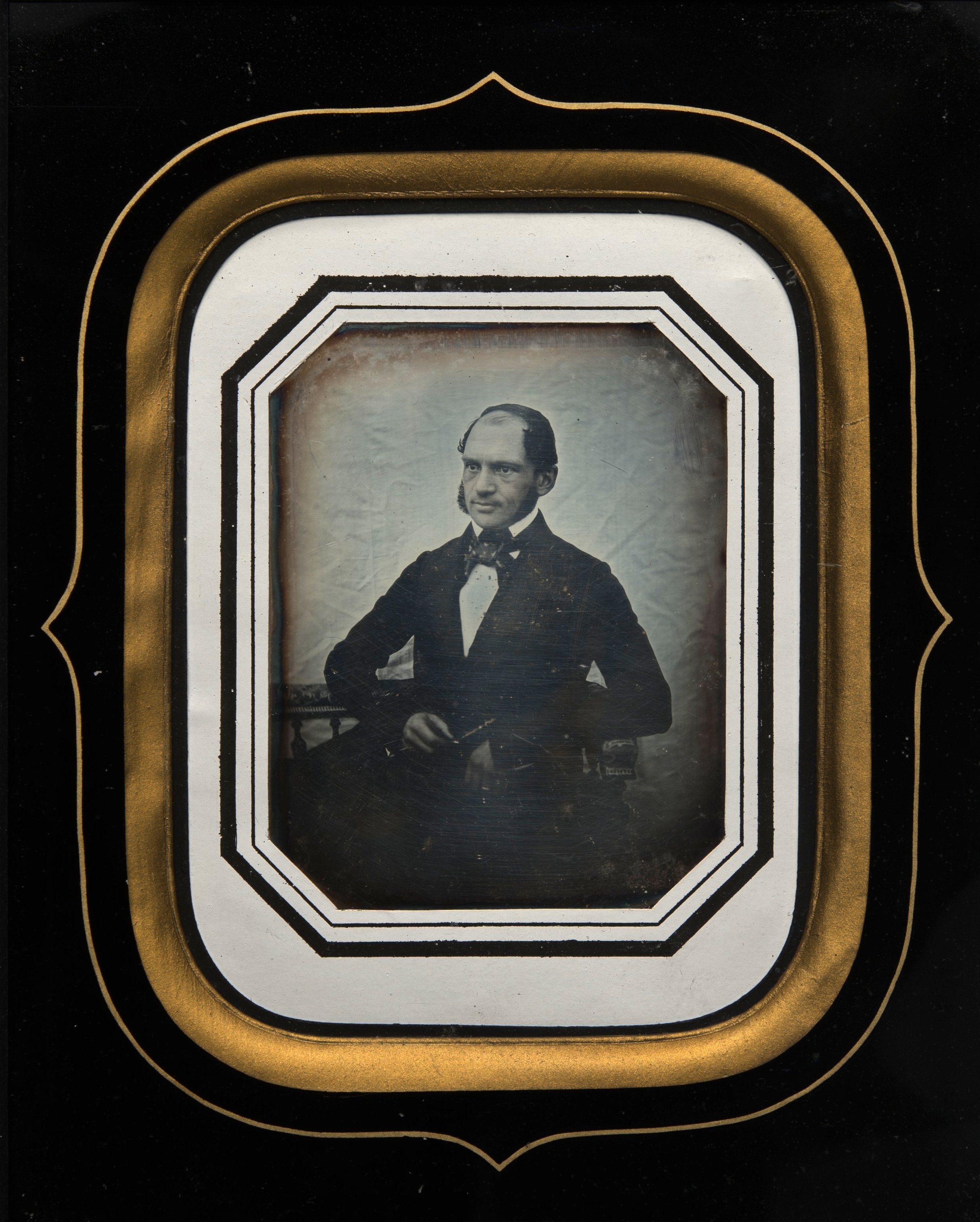

Nevertheless, these few we have offer ample material for research. The biggest collections consisting of five items each belong to the Estonian History Museum, the library of the University of Tartu and the Literary Museum. Most of the daguerreotypes, either donations or purchases, came to the collections only in the 20th century. In most cases it is impossible to say who made them and when they were made. In many portraits, the sitters cannot be ascertained. A pleasant exception is the collection of the Literary Museum, in which all the portrayed people have been recorded. It is known that in addition to portraits several landscapes and examples of architecture were photographed in Estonia, but the collections do not contain any of them.

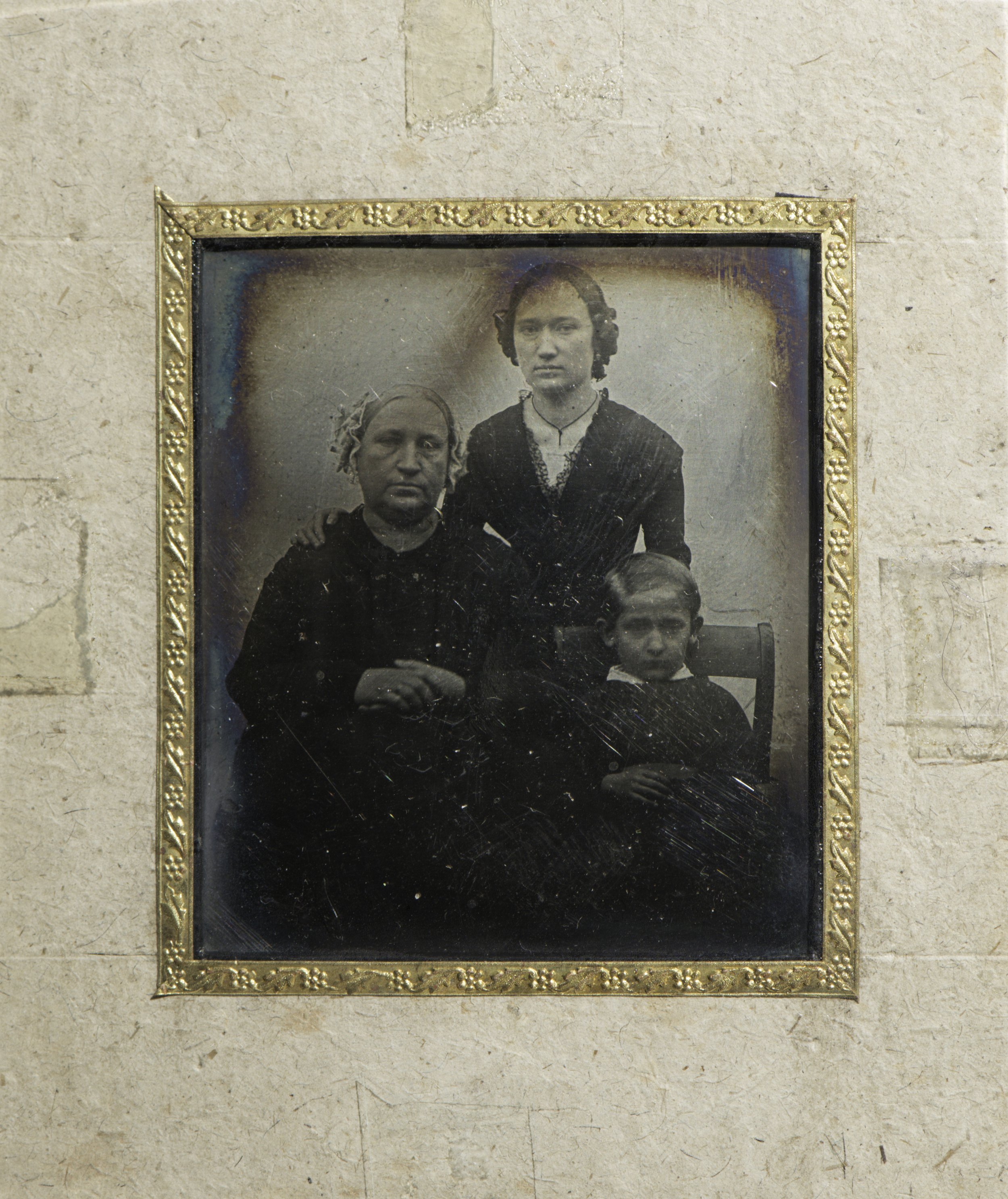

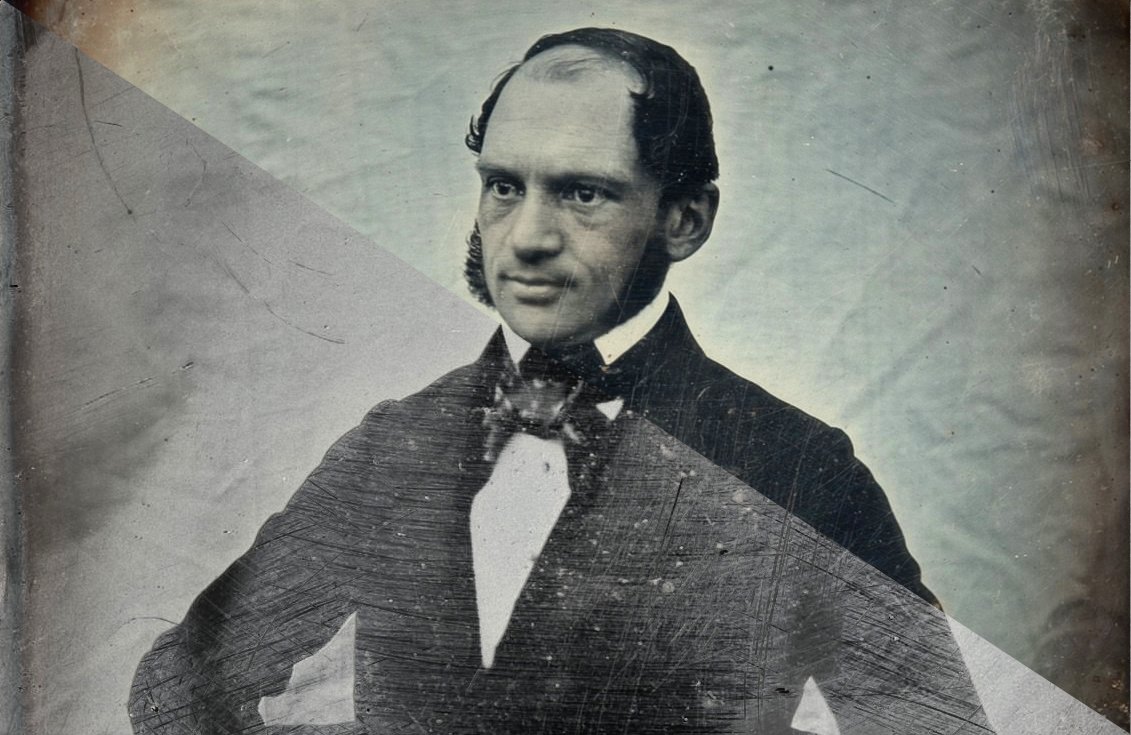

The oldest preserved daguerreotype in Estonia dates from 1844 and was made in St Petersburg. The oldest daguerreotype made in Estonia about 1850 is in the collection of the Järvamaa Local History Museum. Probably made by Carl Borchardt it portrays Tallinn town councillor Alexander Hoeppner. The very last daguerreotype in Estonian collections was made in Narva in 1862. The portrait of writer Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald with his wife, son and daughter was made by Robert Borchardt about 1853.

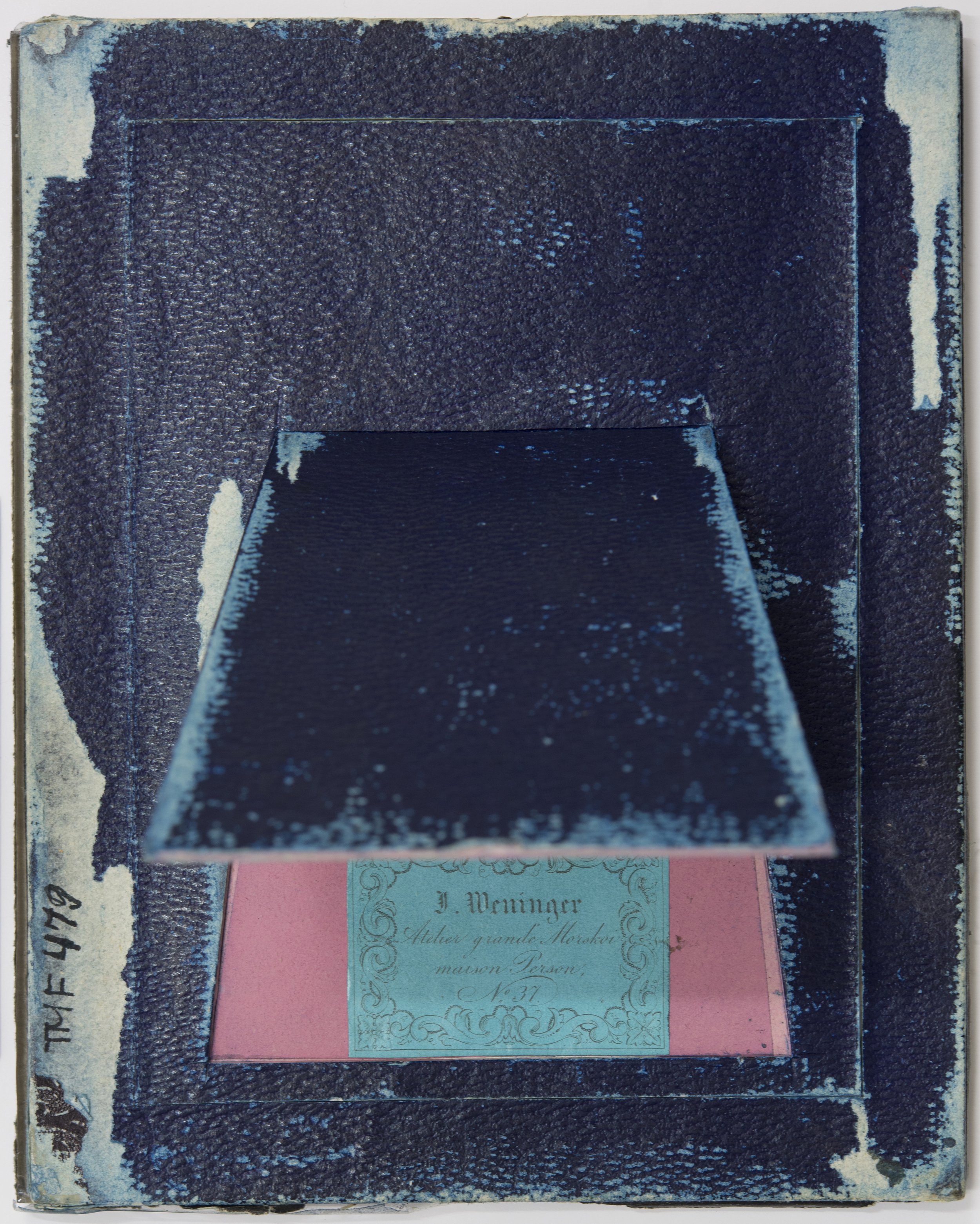

Obviously the daguerreotypes that have preserved in Estonia came from studios in Central Europe or Russia. The only signatures ascertained are those of Joseph Weninger from St Petersburg and R. Borchardt and C. Neuper who worked in Estonia.

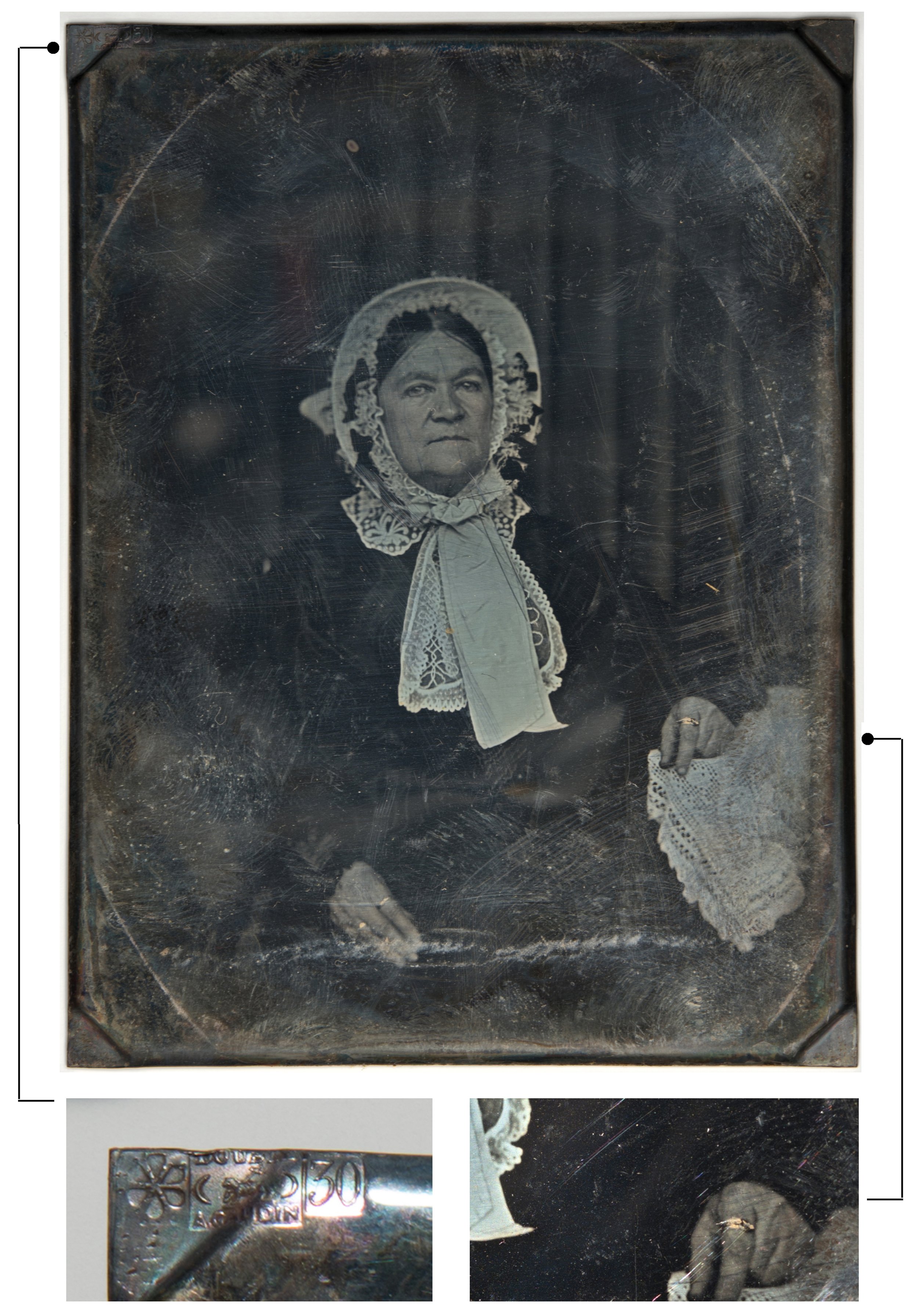

The oldest daguerreotype camera in Estonia can be seen in the museum of the University of Tartu. It was bought for the physics cabinet in 1852. In addition to the camera the museum collection contains two boxes of daguerreotype plate shapes – 0.5 mm thick unexposed silvered copper plates. The standard forms for daguerreotypes used in Estonia were quarter plates (8.1 x 10.8 cm or 3.25 x 4.25 in) and sixth plates (7.2 x 8.1 cm or 2.75 x 3.25 in). The largest daguerreotype in the collection (16.2 x 12.1 cm) was evidently made in St Petersburg.

As the daguerreotypists were active in several countries, the extensive research today needs the availability of various collections. Owing to the initiative of the non-profit association MTÜ Eesti Fotopärand and the support of the Estonian Ministry of Culture daguerreotypes in the Estonian memory establishments’ collections were mapped in 2015 and also entered into the database Daguerreobase. The latter assembles information about the first better-known photographic method from all over Europe with the purpose to make it easier for the researchers of earlier photographic history, promote international co(-)operation and offer the interested people a better idea of the visual culture in the mid-19th century.

When the project was in midstream the PLC Archaeovision digitised the daguerreotypes in Estonia for the first time using the RTI photography. The RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) is a method of serial photography that allows recording the specificity of daguerreotypy, characteristic details (including the hallmark, lines of polishing) of production and also damages of the photos that are barely visible to the naked eye. An interactive digital photo allows studying daguerreotypes in various ways while avoiding damages to the original.

The period of daguerreotypes was rather short. It could not develop further as it was not possible to copy the image. That is why the daguerreotype was ousted in the late 1850s by new negative-positive practices that made it possible to reproduce limitless copies.

Daguerreotypes are valuable, though, as they open up the path of development in photographic techniques and, of course, they represent the earliest portraying of the contemporary people.

Video: https://vimeo.com/121620837

REFERENCES:

Daguerreotype. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daguerreotype

Standardsuuruseid nimetati plaadi mõõtmete järgi: täisplaat 16,2 × 21,6 cm (ingl k whole plate, 6,5 × 8,5 tolli), poolplaat 10,8 × 16,2 cm, kolmandik-plaat 7,2 × 16,2 cm, neljandik-plaat 8,1 × 10,8 cm jne (Daguerreotypes 2014:26). http://issuu.com/daguerreobase/docs/booklet_eng_def?e=11855314/7742785)

Alates 1841. aastast suurendati plaatide valgustundlikkust lisaks joodile ka kloori- ja/või broomiaurudes (Daguerreotypes 2014:21)

Daguerreotypes 2014: 37- 43

Osterman 2007: 28

1840. aastal L. A. H. Fizeau’ poolt leiutatud viimistlusmeetod, mis seisnes kujutise töötlemises kuldkloriidi lahusega, aitas vähendada hõbeda oksüdeerumist ja parandas tunduvalt dagerrotüüpide säilivust. (Daguerreotype FoMu : 4)

Tooming 1990:11, 60-61; Daguerreotype FoMu: 3-4

1850. aastal võeti plaatide hõbetamiseks kasutusele galvaaniline meetod, mis andis kvaliteetsema lõpptulemuse ja vähendas dagerrotüüpide lõpphinda. Daguerreotype FoMu: 4

Tooming 1990: 11, 60-61; Daguerreotype FoMu: 3-4

Osterman 2007: 28

Valverde 2005: 6. https://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/webfm_send/302

Revalsche wöchentliche Nachrichten (edaspidi RwN), 19.06.1850, lk 750–751 (Teder 1972: 23)

Sallas 2015: 32

Gruber, Ha 2005: 237

Liibek 2010: 71; Sallas 2015: 26-27; vt ka http://daguerreotypearchive.org/

Rigasche Zeitung (RZ), 10.08.1839, 24.08.1839, 26.08.1839 (Liibek 2010: 71).

RwN, 05.08.1840, lk 876.

Liibek 2010: 74, 78

Samas, lk 78, 82–83.

RwN, 01.05.1844, lk 479

Liibek 2010: 158

Dörptsche Zeitung, 14.07.1844; 28.07.1844 (Liibek 2010: 76)

Liibek 2010: 165, 168

Liibek 2010: 76-77

RwN, 24.04.1850, lk 450–451 (Liibek 2010: 76-78)

RwN, 16.06.1852, lk 844 (Liibek 2010: 79)

10 hõberubla maksis nt aurulaeva kajutipilet Tallinnast Peterburi või kolmetoalise korteri kuuüür Tallinna vanalinnas. (Liibek 2010: 75-76)

Samas, lk 79, 81, 90, 155–156

Tooming 1977; Tooming 1982. Fotosaated: Hõbedane ime“, rež Peeter Tooming, 1995, https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/fotosaated-hobedane-ime

Vt Daguerreobase: http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/

Teder 1972: 25

AM 8832 F 5801, AM F 20114:1, AM F 20114:2, AM F 20114:3, AM F 31759

TÜ Raamatukogu fotokogu, F 169, s 1–5.

EKLA A-37:1254, EKLA B-37:1478, EKLA reg. 1940/28, EKLA A-12:2, EKLA B-85:112

SA Ajakeskus Wittenstein/Järvamaa Muuseum, PM F 22, PM F 23

TLM 4929 KA 672, TLM F 9701

HM 1491 Ff

TM F 479

EAA f 1862 n 2 s 472, foto 3

Asmer 2015: 8-13

Tooming 1990: 12-13

Liibek 2010: 232

Samas, lk 229

SA Ajakeskus Wittenstein/Järvamaa Muuseum, PM F 22

SA Haapsalu ja Läänemaa muuseumid, HM 1491 Ff

Eesti Kirjandusmuuseum, EKLA A-12:2. (Liibek 2010: 80, 165)

Vt Daguerreobase: http://daguerreobase.org/en/browse/

Kaamera: ÜAM 45:53 / Aj; Karbid ja plaadid: ÜAM 21:1-13 / AjKF 12:1-13, ÜAM 1112:16 / AjKF (Meilivestlus Tullio Ilometsaga, juuni 2015)

Eesti Kirjandusmuuseum, EKLA reg. 1940/28

Stereofotosid valmistati spetsiaalse stereokaameraga, mille kahe objektiivi optiliste telgede vahekaugus oli sarnane inimese silmade vahelise kaugusega. Kahe sarnase kujutise vaatlemisel läbi spetsiaalse seadeldise – stereoskoobi – moodustus üks ruumiline kujutis. Vt Ilomets 1977; Ilomets 1989.

Nt 20, 30 või 40. Number viitab hõbeda ja vase koguse suhtele: „40“ tähendab, et ühe osa hõbeda kohta sisaldab dagerrotüüp-plaat 39 osa vaske. Daguerreotypes. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/dag/glossary.html

Digiteerimistööd viis läbi Archaeovision OÜ, vt http://archaeovision.eu/et/

Vt pildistusmeetodite võrdlust: Wachowiak, Webb

1. osa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzolOGIMS18

54. Pagi, Miles, Uueni 2015: 14-21

Asmer, Vilve. Daguerreotypes in the photographic collection of the Estonian Literary Museum. – Daguerreotype Journal, nr 2/2015. Toim Sandra M. Petrillo. European Daguerreotype Association, 2015, lk 8–13.

Daguerreobase. Kättesaadav: http://daguerreobase.org/

Daguerreotype. FoMu – Restoration & Conservation. Koost Ann Deckers, Herman Maes. Antwerpen: FotoMuseum Provincie Antwerpen (Fomu).

Daguerreotypes. Europe's earliest photographic records. Daguerreobase Consortium, 2014, http://issuu.com/daguerreobase/docs/booklet_eng_def?e=11855314/7742785

Daguerreotypes. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/dag/glossary.html

Fotosaated „Hõbedane ime“, rež Peeter Tooming, 1995, https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/fotosaated-hobedane-ime

Gruber, Andreas; Ha, Taiyoung. A History of Zapon Lacquer Coating and Its Use on the Daguerreotypes in the Albertina Photograph Collection. – Coatings on Photographs: Materials, Techniques and Conservation. Koost McCabe, Constance. Washington D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Photographic Materials Group, 2005, lk 236–253.

Ilomets, Tullio. Haruldane fotokogu Toomel. – Edasi, 18.09.1977.

Ilomets, Tullio. Unikaalne leid Tartu Ülikoolis päevapildi juubeli aastal. – Edasi, 17.12.1989.

Liibek, Tõnis. Fotograafiakultuur Eestis 1839–1895. Doktoritöö. Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikool, Kunstide Instituut, 2010.

Osterman, Mark. Introduction to Photographic Equipment, Processes, and Definitions of the 19th Century. – The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography. Amsterdam [jt]: Focal Press, 2007, lk 36–123.

Pagi, Hembo; Miles, James; Uueni, Andres. Re-illuminating the past: Introduction to Reflectance Transformation Imaging. – Daguerreotype Journal, nr 2/2015. Toim Sandra M. Petrillo. European Daguerreotype Association, 2015, lk 14–21.

Revalsche wöchentliche Nachrichten (RwN), 05.08.1840.

Revalsche wöchentliche Nachrichten, 01.05.1844.

Sallas, Laura. A silver window on history: Daguerreotypes in Finland in the 19th century. – Daguerreotype Journal, nr 2/2015. Toim Sandra M. Petrillo. European Daguerreotype Association, 2015, lk 24–37.

Teder, Kaljula. Eesti fotograafia teerajajaid. Sada aastat (1840–1940) arenguteed. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1972.

Tooming, Peeter. Eesti fotograafia ajaloost I. Fotoharuldused. – Sirp ja Vasar, 02.09.1977. Tooming, Peeter. Eesti fotograafia ajaloost 9. Ikka rariteetidest. – Sirp ja Vasar, 18.06.1982.

Tooming, Peeter. Hõbedane teekond. Tallinn: Valgus, 1990.

Tooming, Peeter. Kas nüüd siis kõige vanem dagerrotüüp? – Päevaleht, 05.03.1993.

Valverde, Maria Fernanda. Photographic Negatives: Nature and Evolution of Processes. Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation. Rochester: George Eastman House, Image Permanence Institute, 2005. Kättesaadav: www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/webfm_send/302

Wachowiak, Mel; Webb, Keats. Updated Methods for Digitization of Daguerreotypes (Part 1–3). Ettekanne konverentsil „Daguerreian Society Symposium”, 2012 (Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute).

1. osa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzolOGIMS18;