CONSERVING THE TREASURE BINDING OF THE OLD BELIEVERS GOSPEL FROM THE ISLAND OF PIIRISSAAR

Autor:

Grete Ots, Tulvi-Hanneli Turo, Ruth Paas

Number:

Anno 2019/2020

Category:

Conservation

In the night of May 16, 2016 an unexpected and sad event happened to Peipsiveere Old Believers, known best for their onions, samovar-made tea and boiled candy. Three homes were burnt down and the chapel [ill 1] suffered as well. Only a few of the congregation’s valuable collection of icons and heritage books kept in the chapel were rescued. (1), [ill 2]

Specialists of Estonian National Archives department in Tartu were the first to evaluate the damages and carry out the initial drying of the bindings on the spot. Later on conservators from the Tallinn City Archives, corresponding departments of the National Archives of Estonia in Tartu and Tallinn, the Estonian National Museum, the University of Tartu Library and the National Library of Estonia joined in. (2),(3),(4)

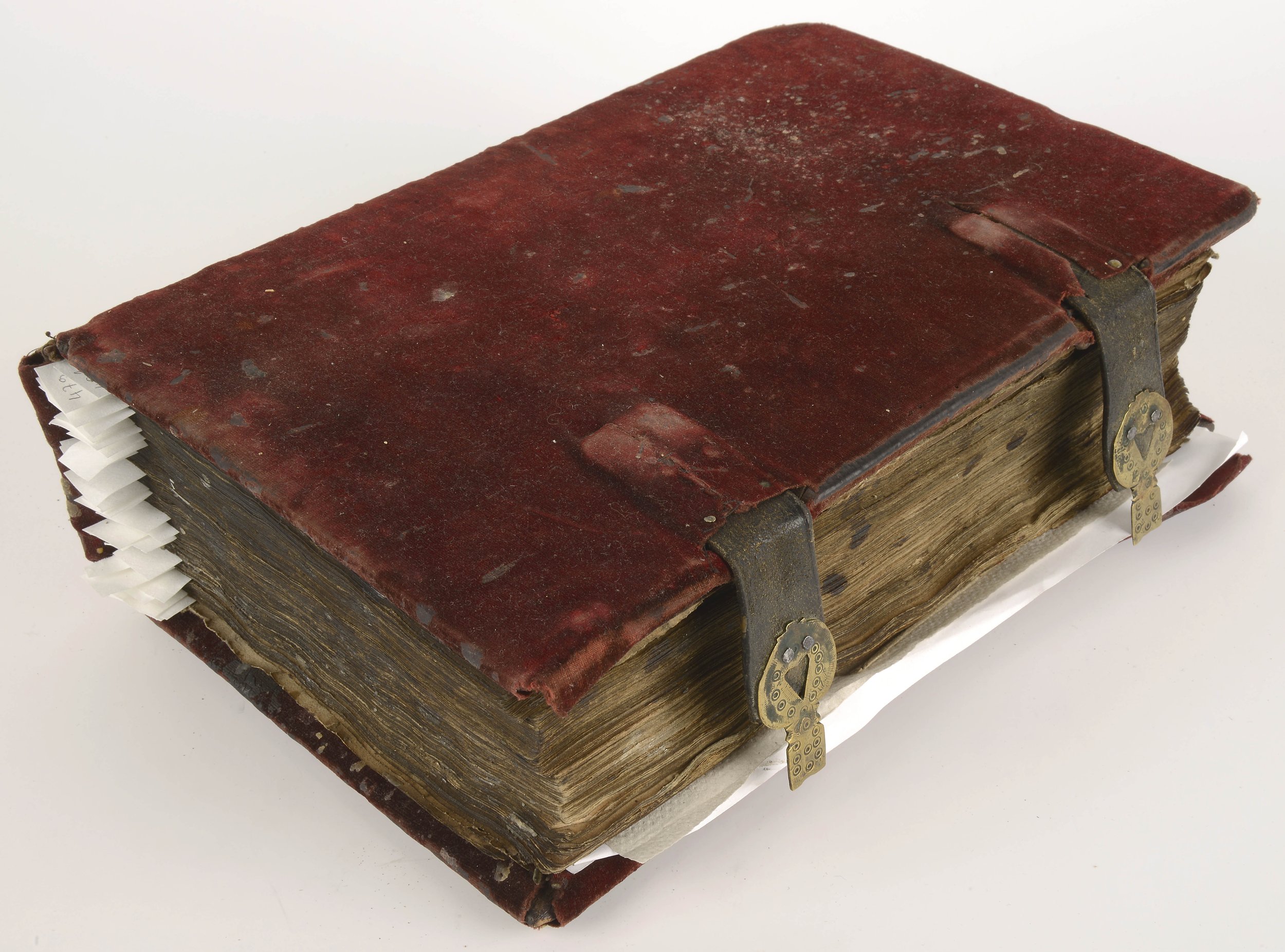

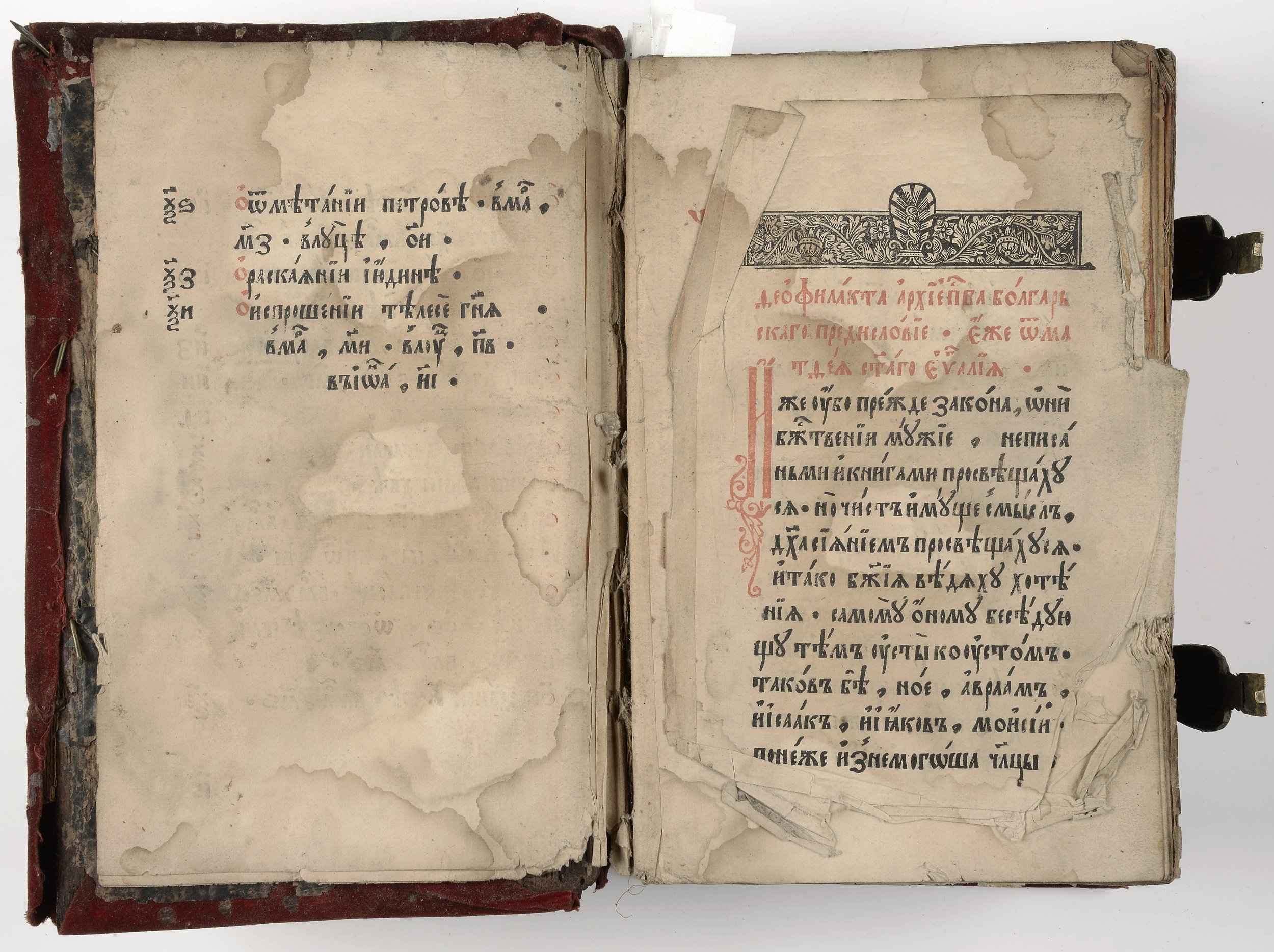

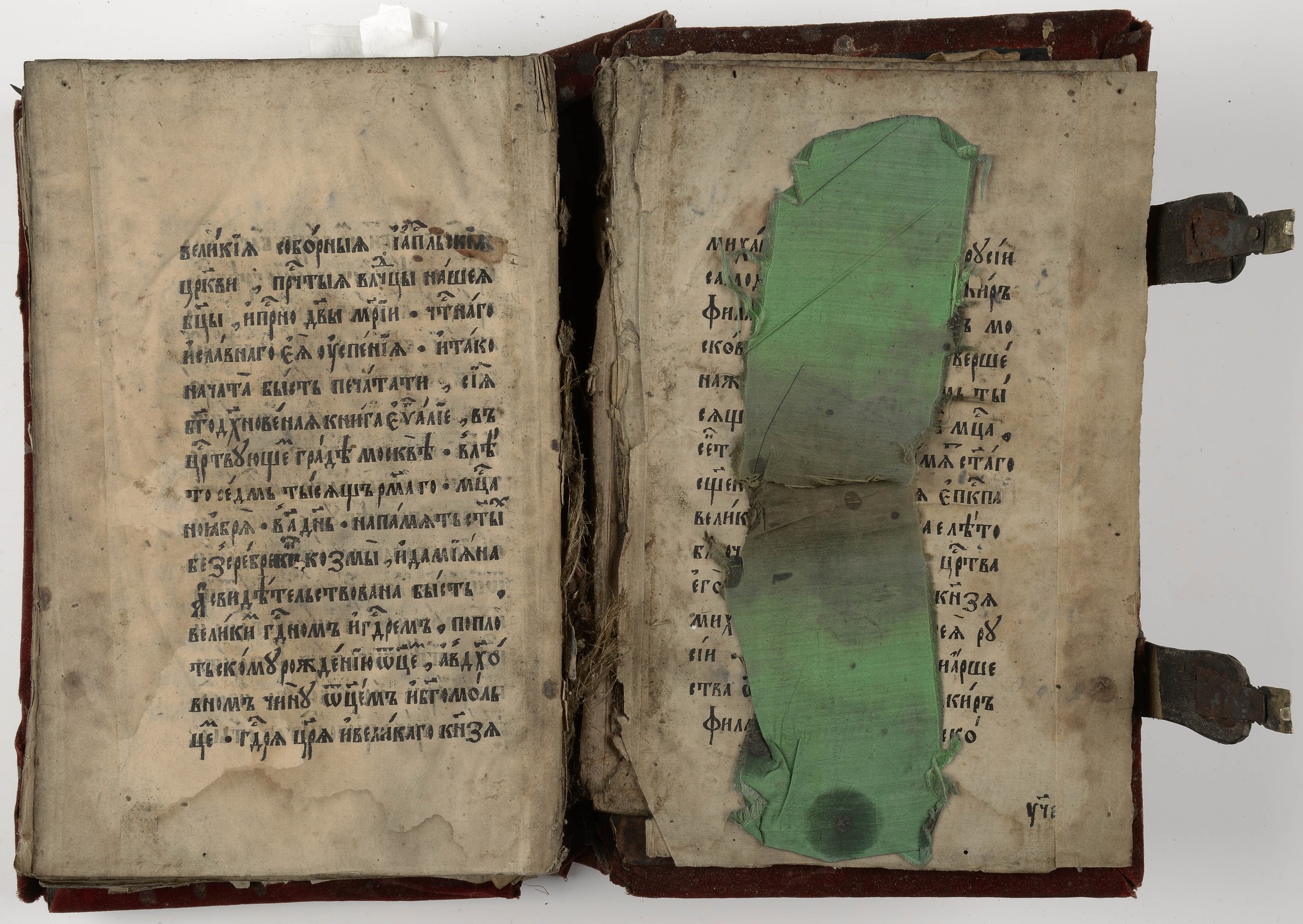

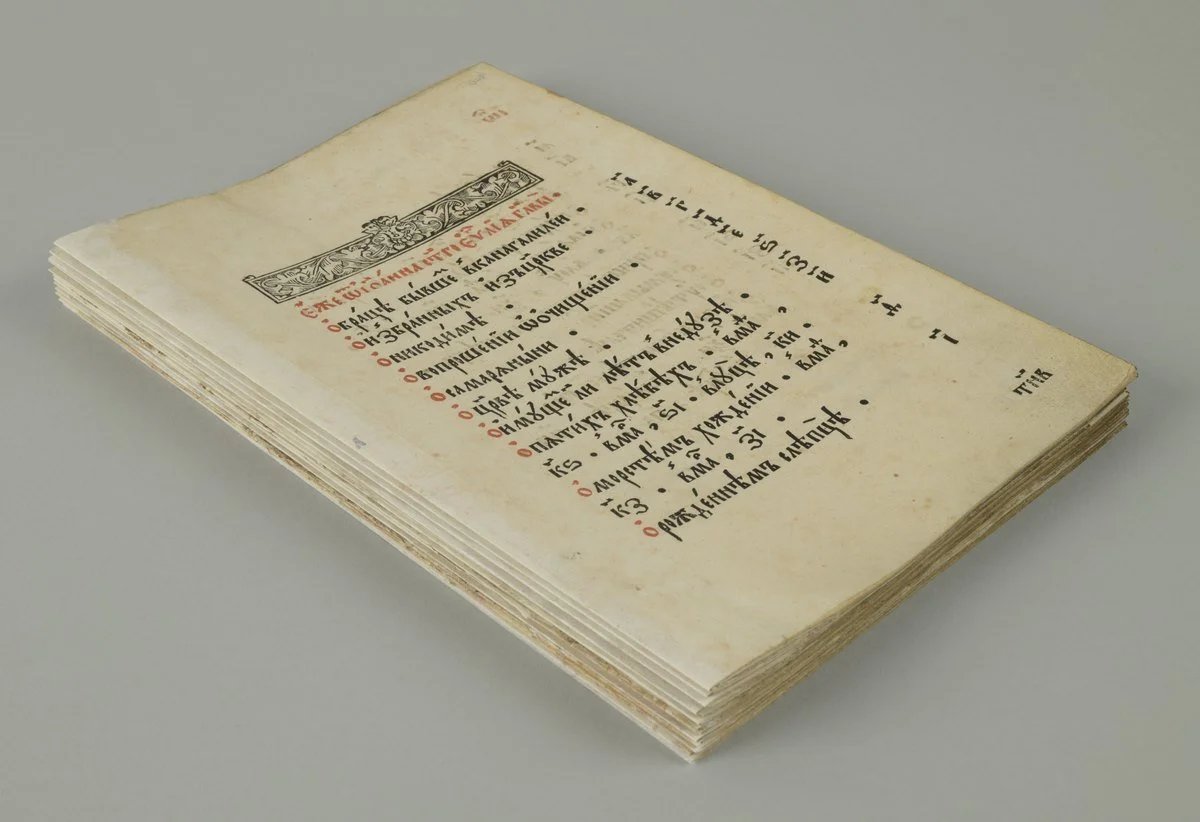

One of the rare books rescued from the fire is the Gospel, published in Moscow in 1633. The present article focuses on the conservation of just this binding at the Conservation Centre Kanut.(5), (6)

Sacred books have a special place in the Old Believers’ tradition, the schism within the Russian Orthodox Church started just about the same time as the reforms of liturgical literature. The Gospel under discussion was published before the reforms started in 1653 and thus it belongs to the gold reserve of the old books, being one of the 145 publications, printed in between 1631 and 1650 by the Moscow Printing House. (7), (8)

Drying up the Gospel

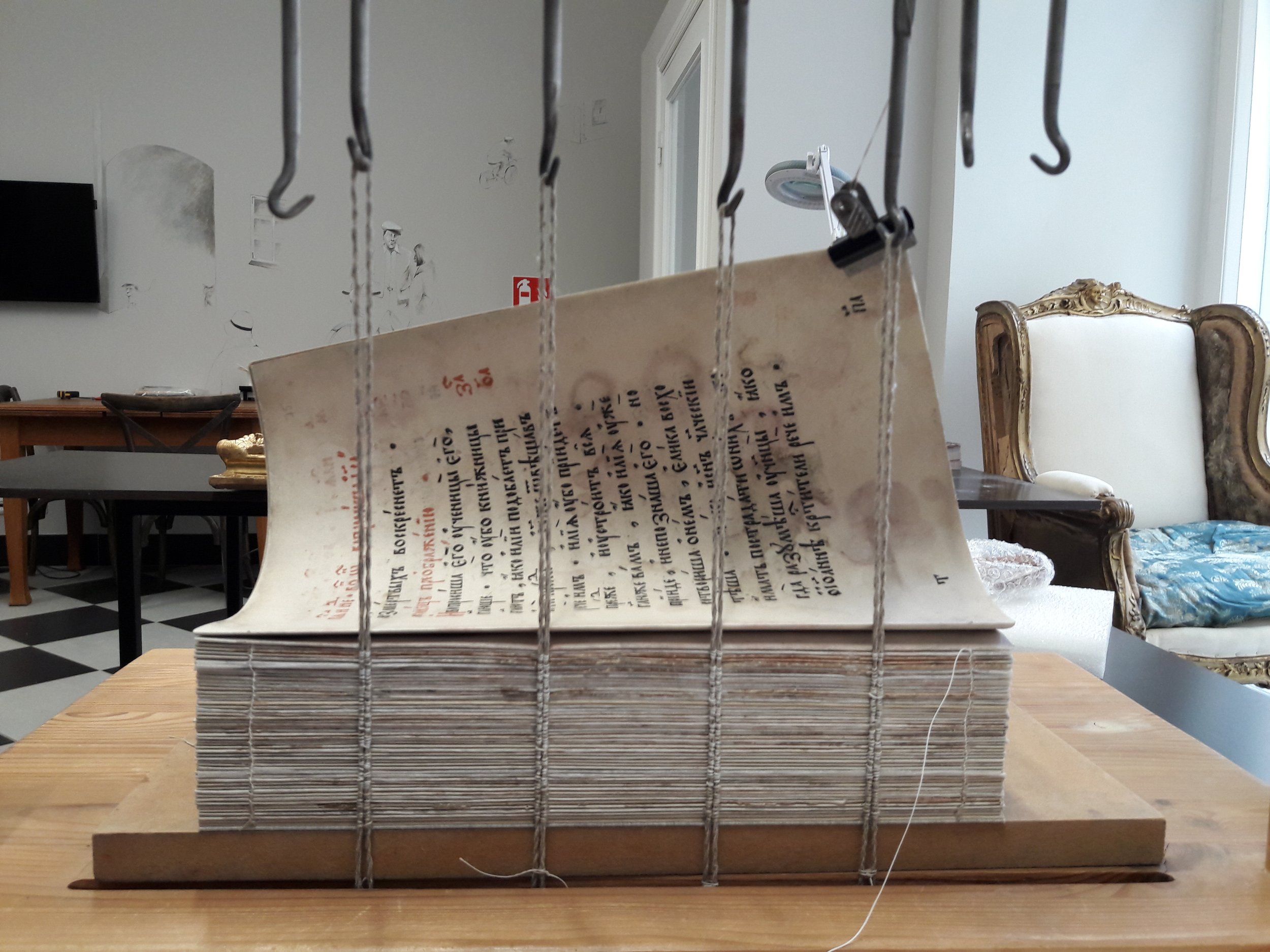

To prevent deformation and mold damage, the 500-page binding with its soaked-through covers had to be dried quickly. (9)The Gospel was brought away from the island and taken for lyophilization to Tallinn University Institute of History, Archaeology and Art History already on May 17. [ill 3]

The Gospel was dried for 36 hours in the freezer Sublimator 700 at the conservation laboratory. First of all, pre-freezing down to -20° was accomplished. Various warming up cycles by infrared radiation followed. After every warming-up cycle freezing was repeated. (10) Tarvi Toome, conservator of the archaeology research centre at Tallinn University was responsible for the processing. Deformation of the damaged binding was minimal after the drying process and it was possible to close it again in the original manner. [ill 4], [ill 5]

Description of the Gospel

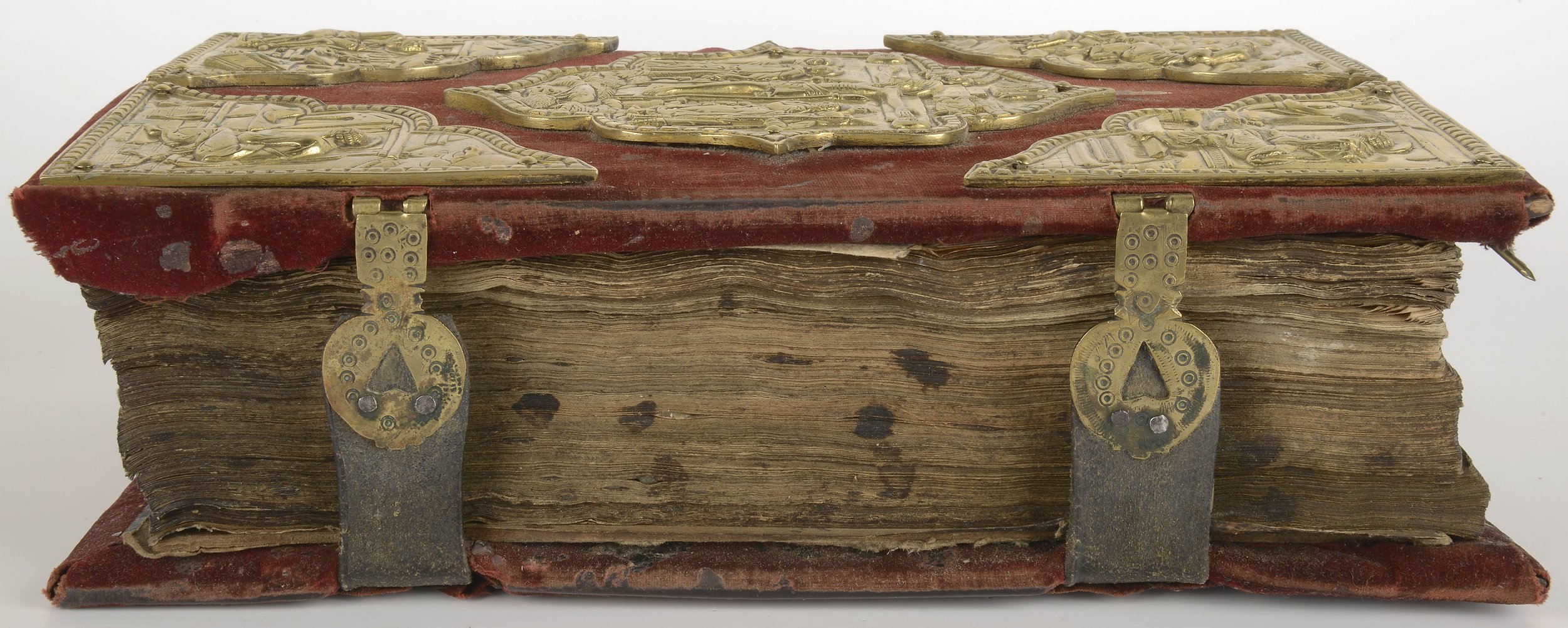

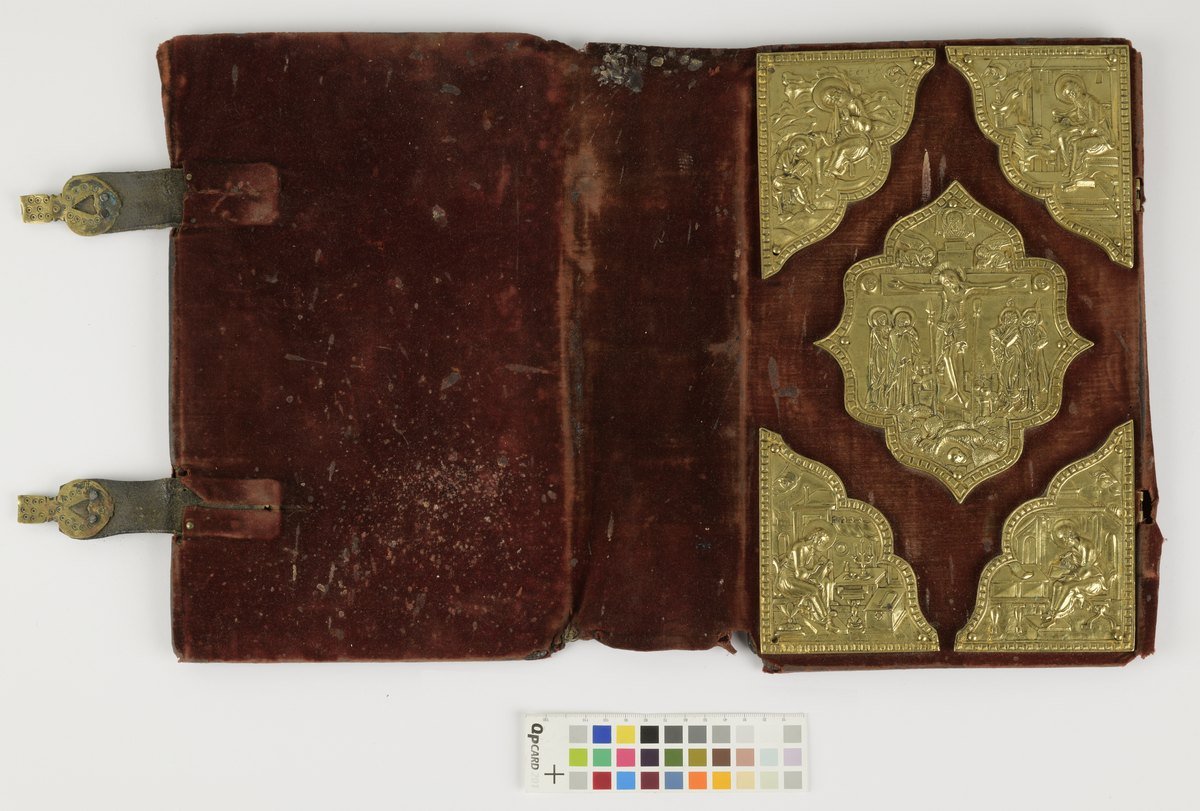

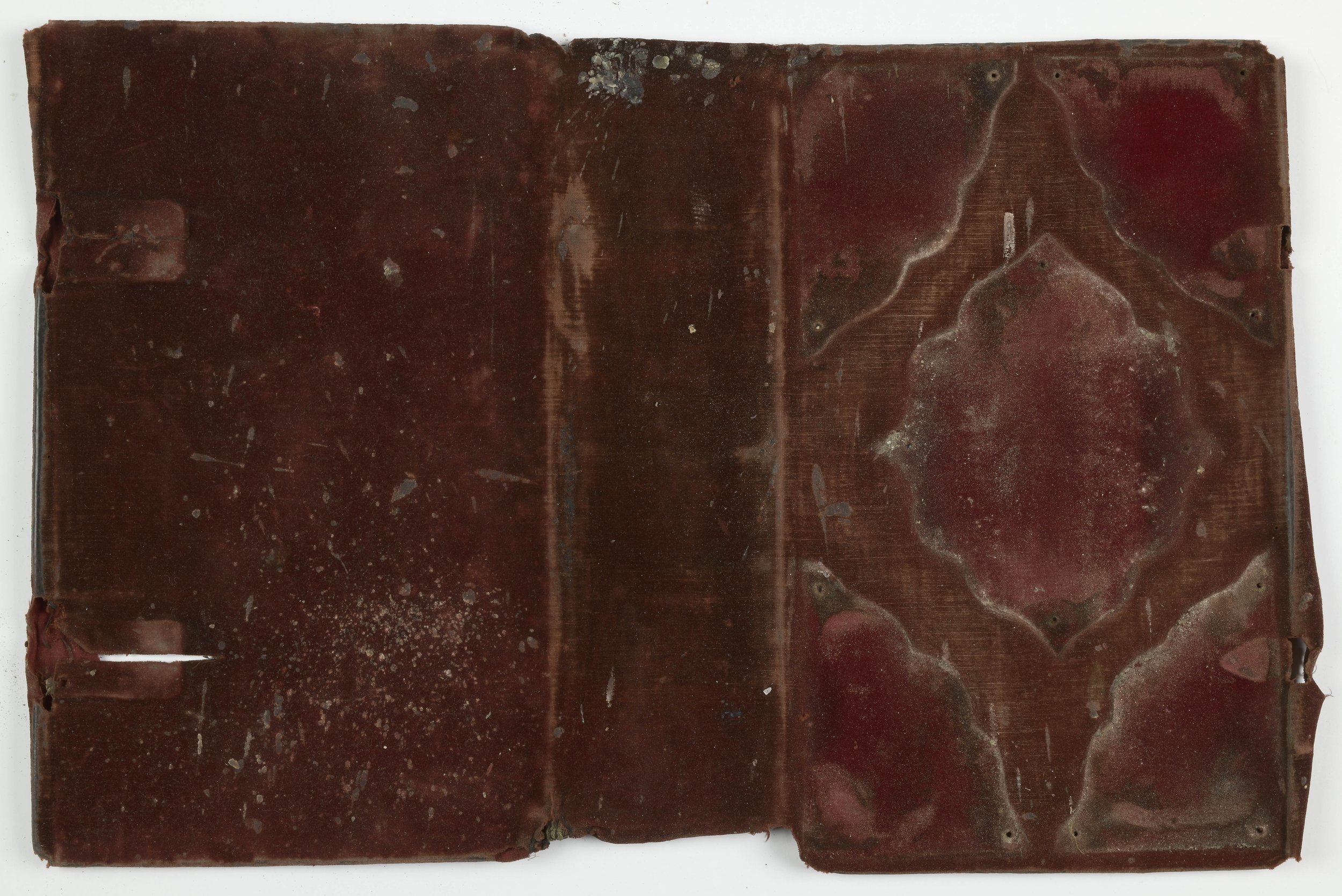

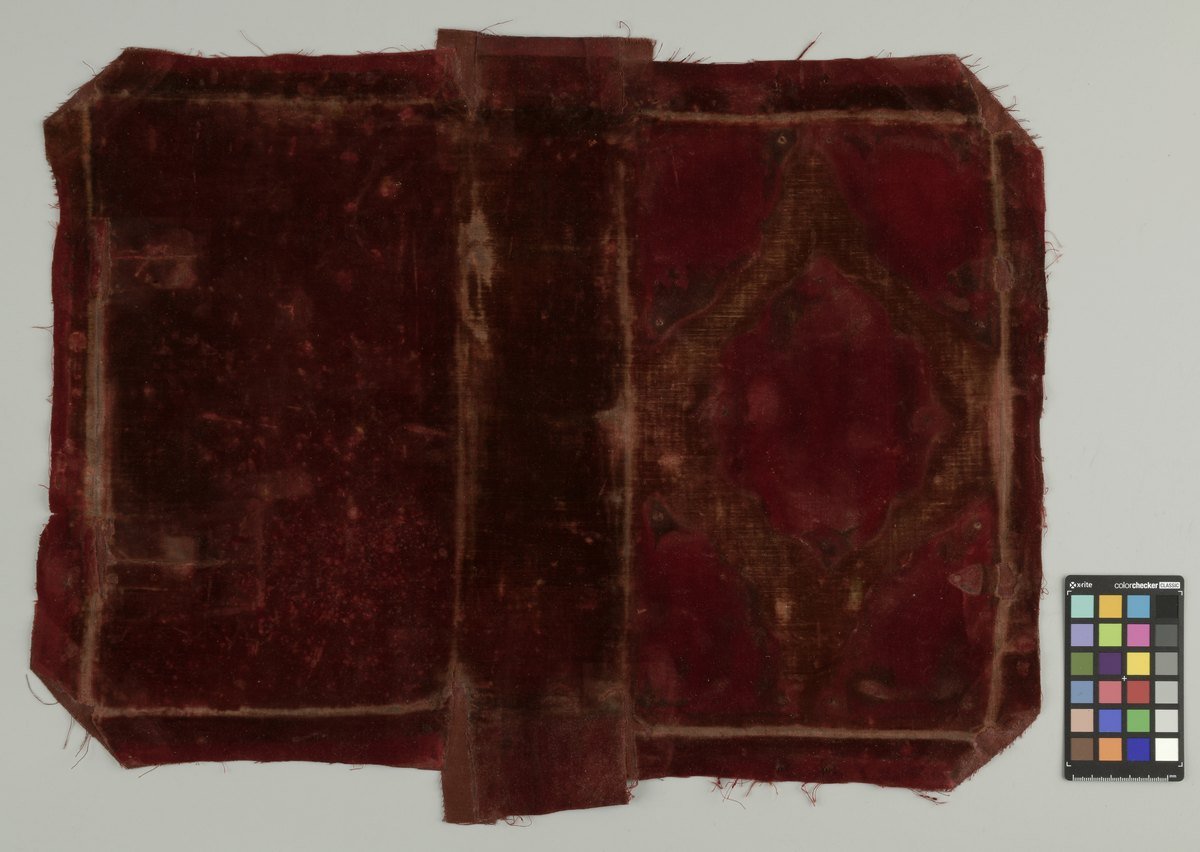

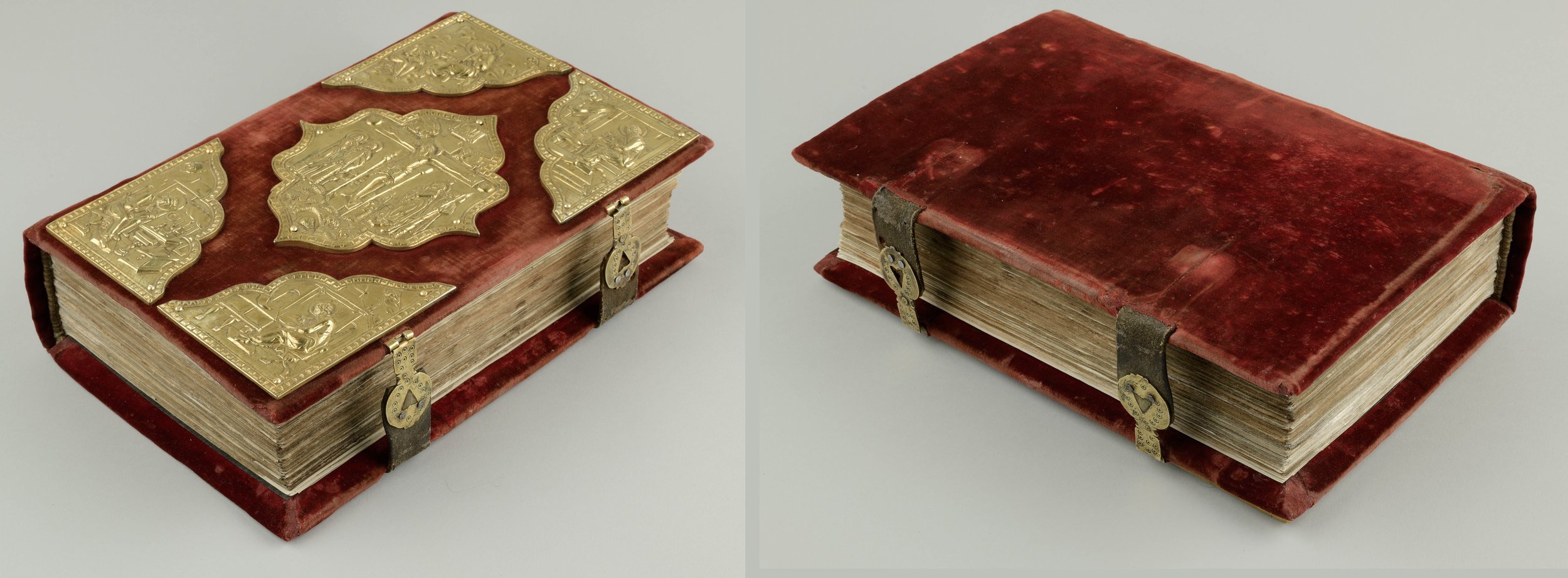

The oak boards of the binding are covered with red silk velvet. The front cover is decorated with five bronze plaques – four in the corners are depicting the evangelists and the central one carries the image of crucified Christ. [ill 6]

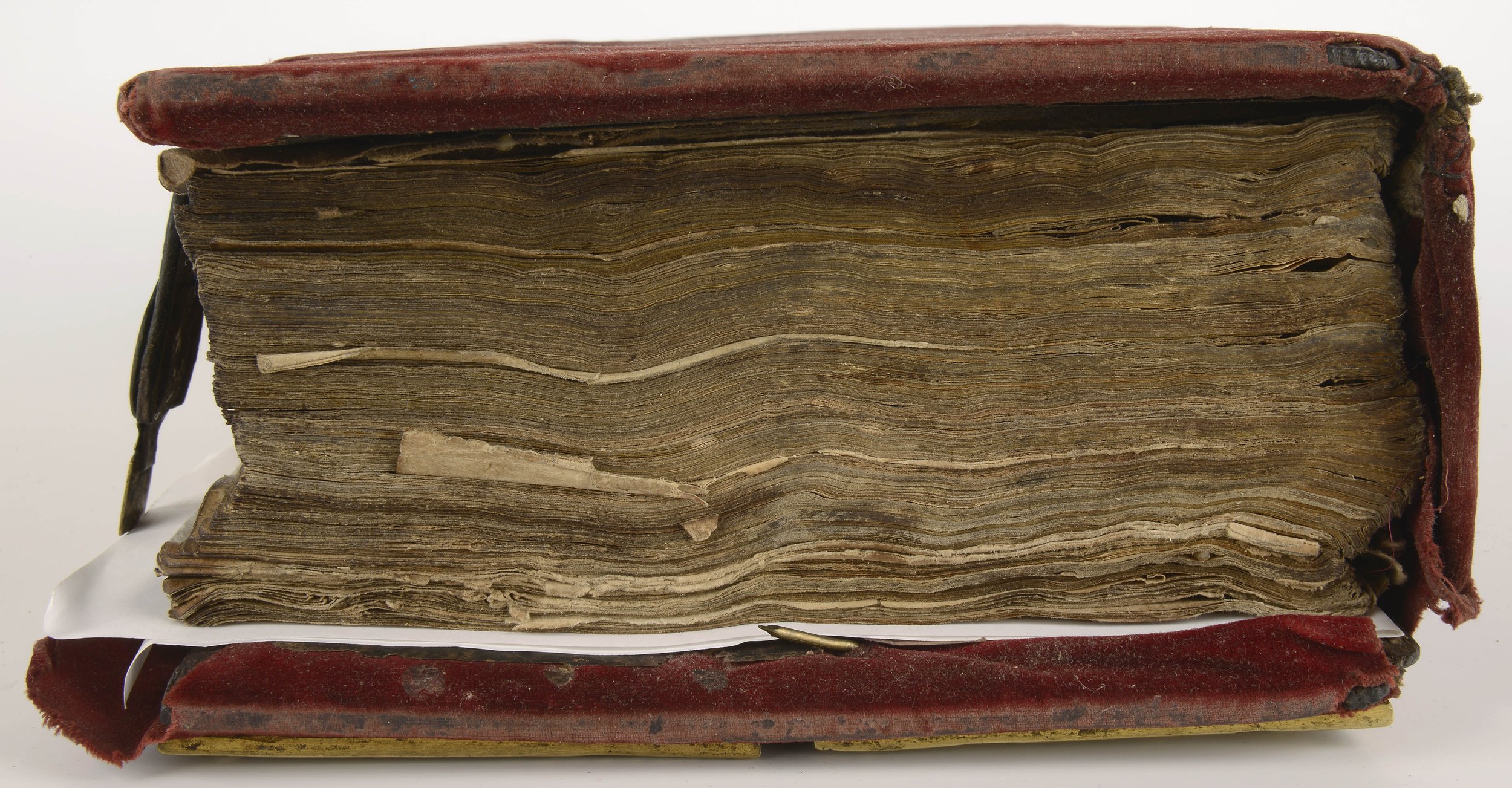

The edges of the boards have been rounded on the outside and inner sides of the edges have been also rounded for about 10-15mm. Decorative plaques have been fixed with long nails, ends bent back on the inner side of the board. The binding has been locked with decorated clasps. In the centre of the hasp is a heart-shaped hole. [ill 7], [ill 8] The catcher plates of the hasps have been fixed on the outer edge of the front board with nails driven into the velvet covered surface. The hasps are on leather straps fixed on the back board. Velvet textile has been slit for the straps that are fixed with nails in the wood under the fabric. The straps are fastened on the hasps with two nails and a riveted metal tablet. (11) Handsewn headbands on the edge of the fabric on the block’s spine have survived.

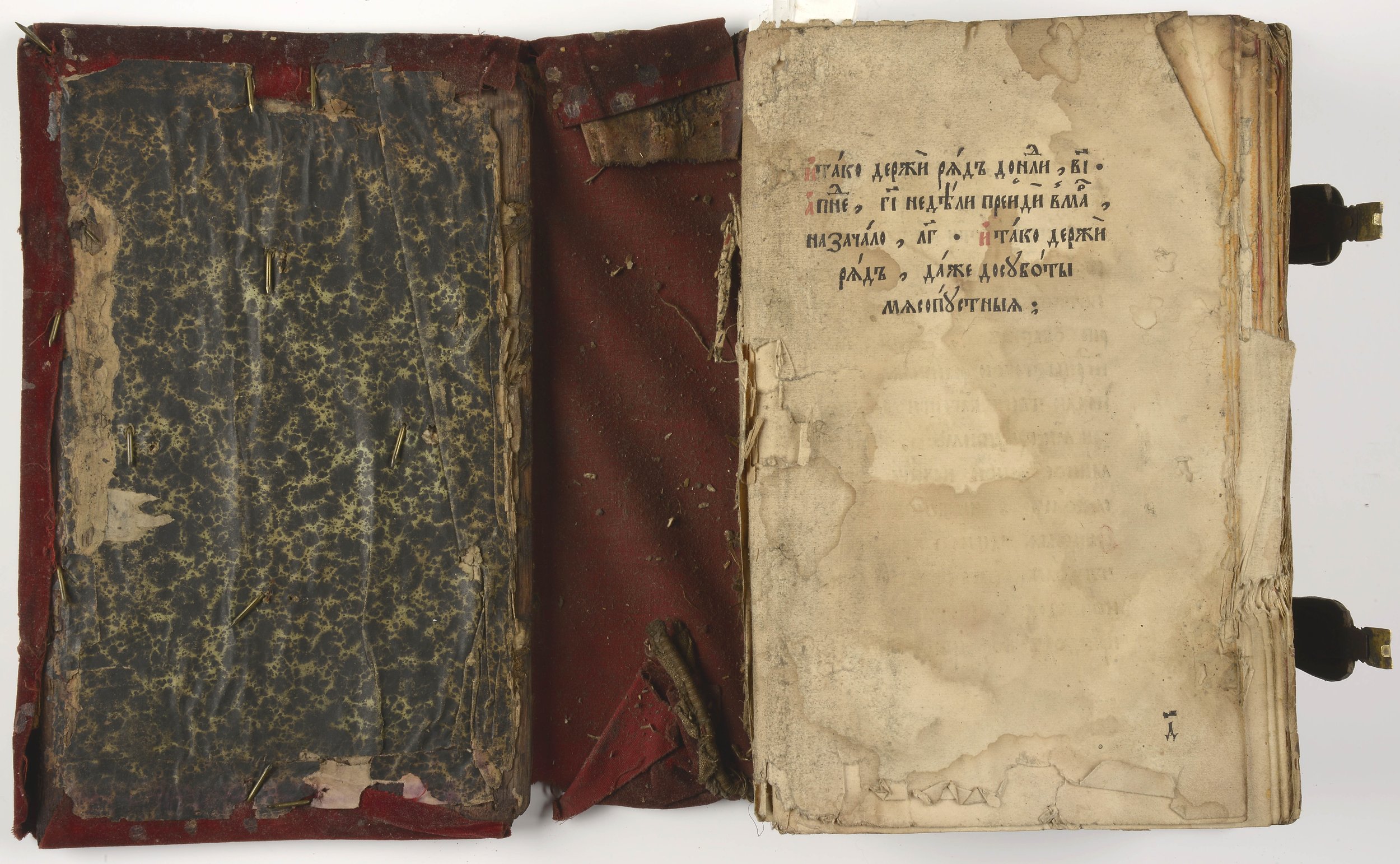

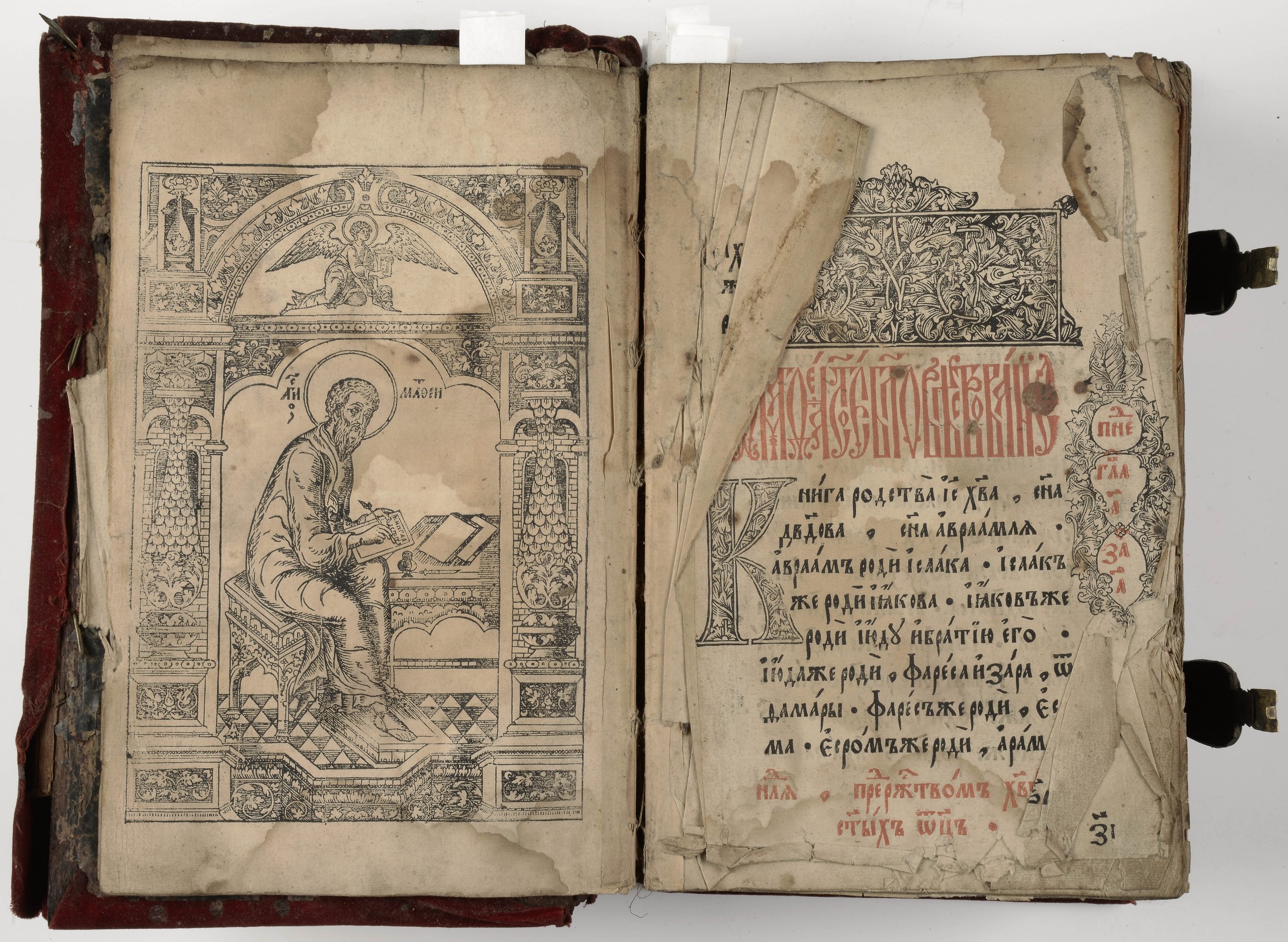

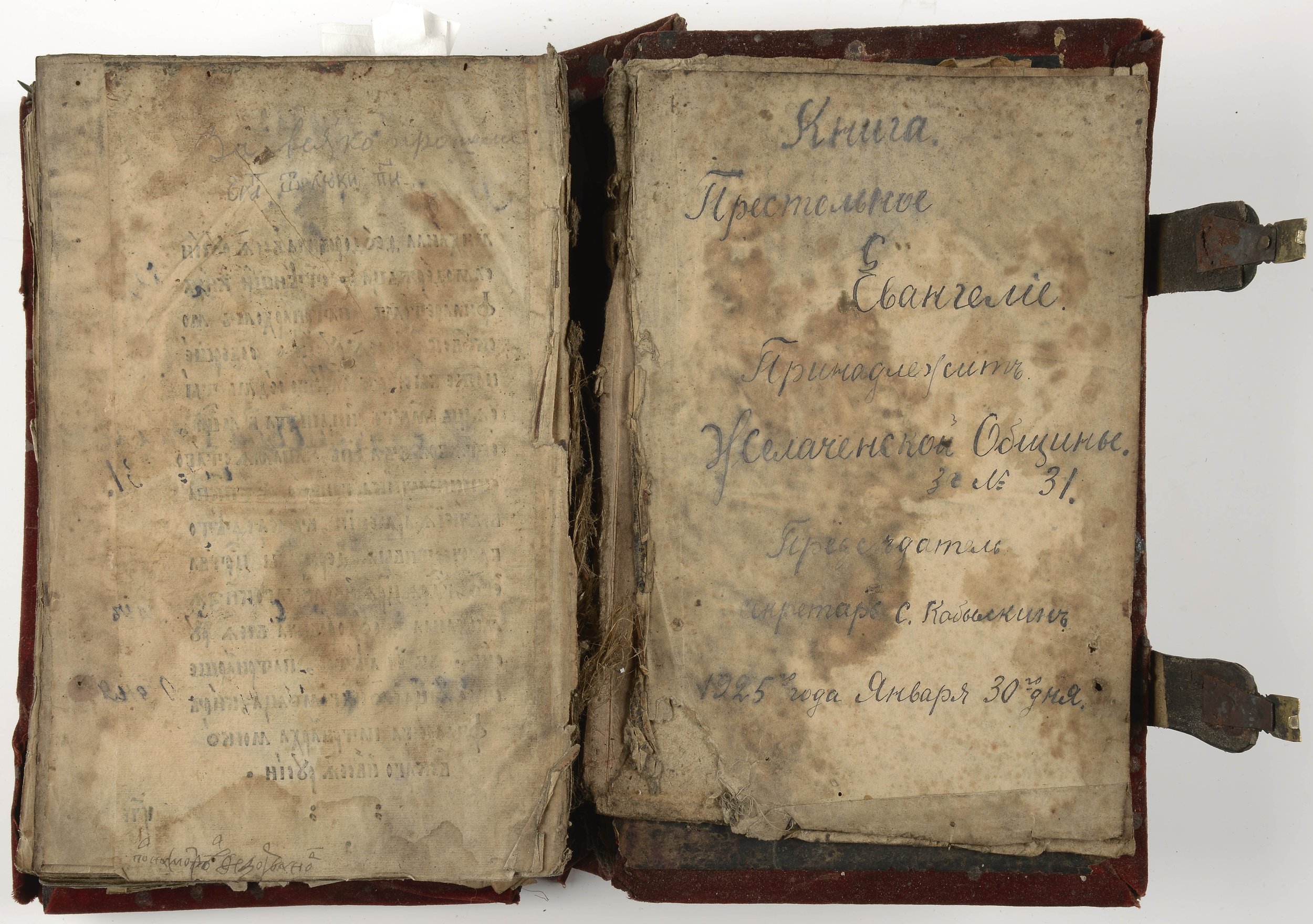

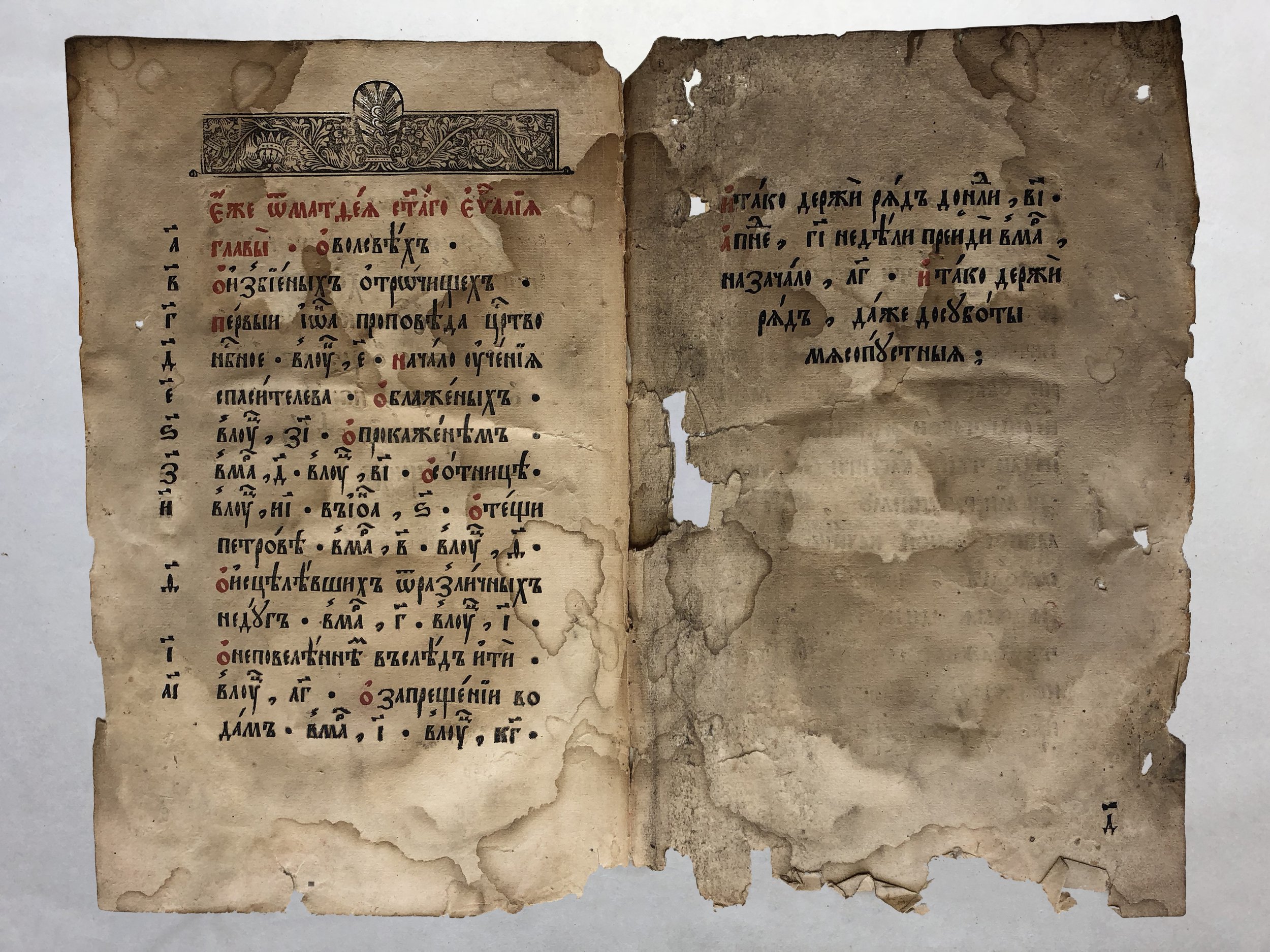

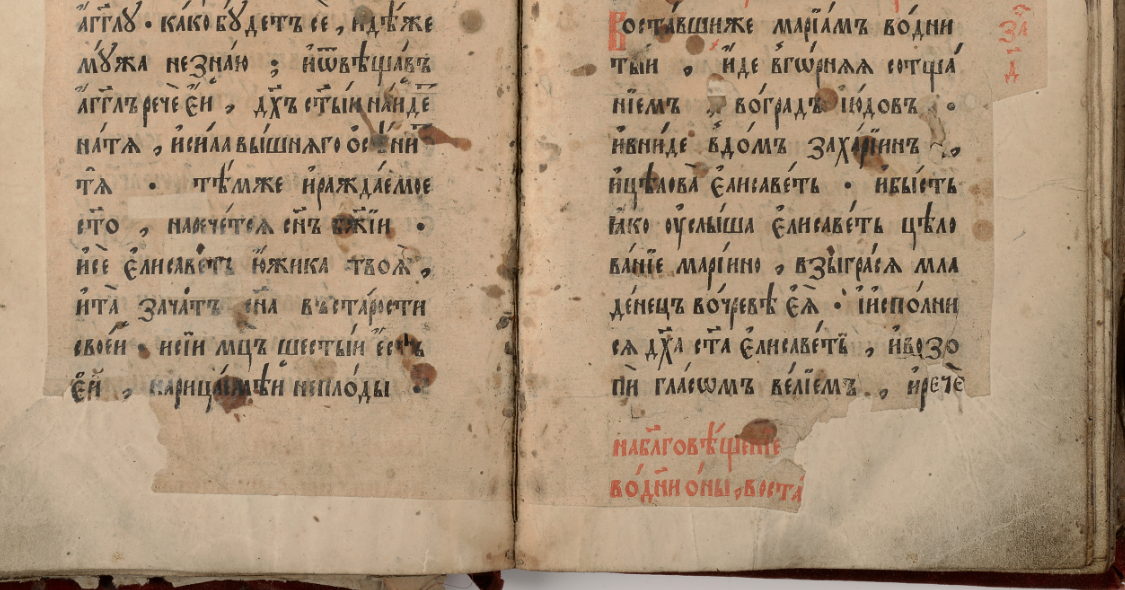

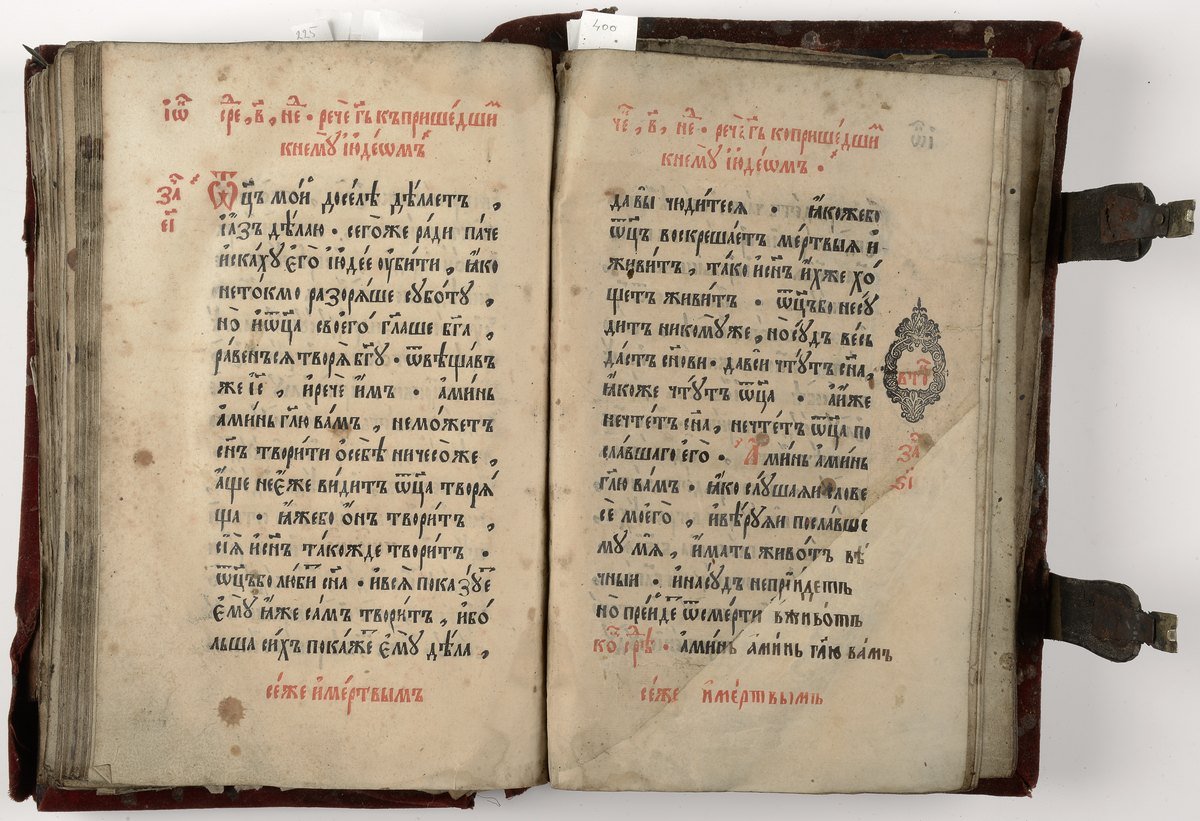

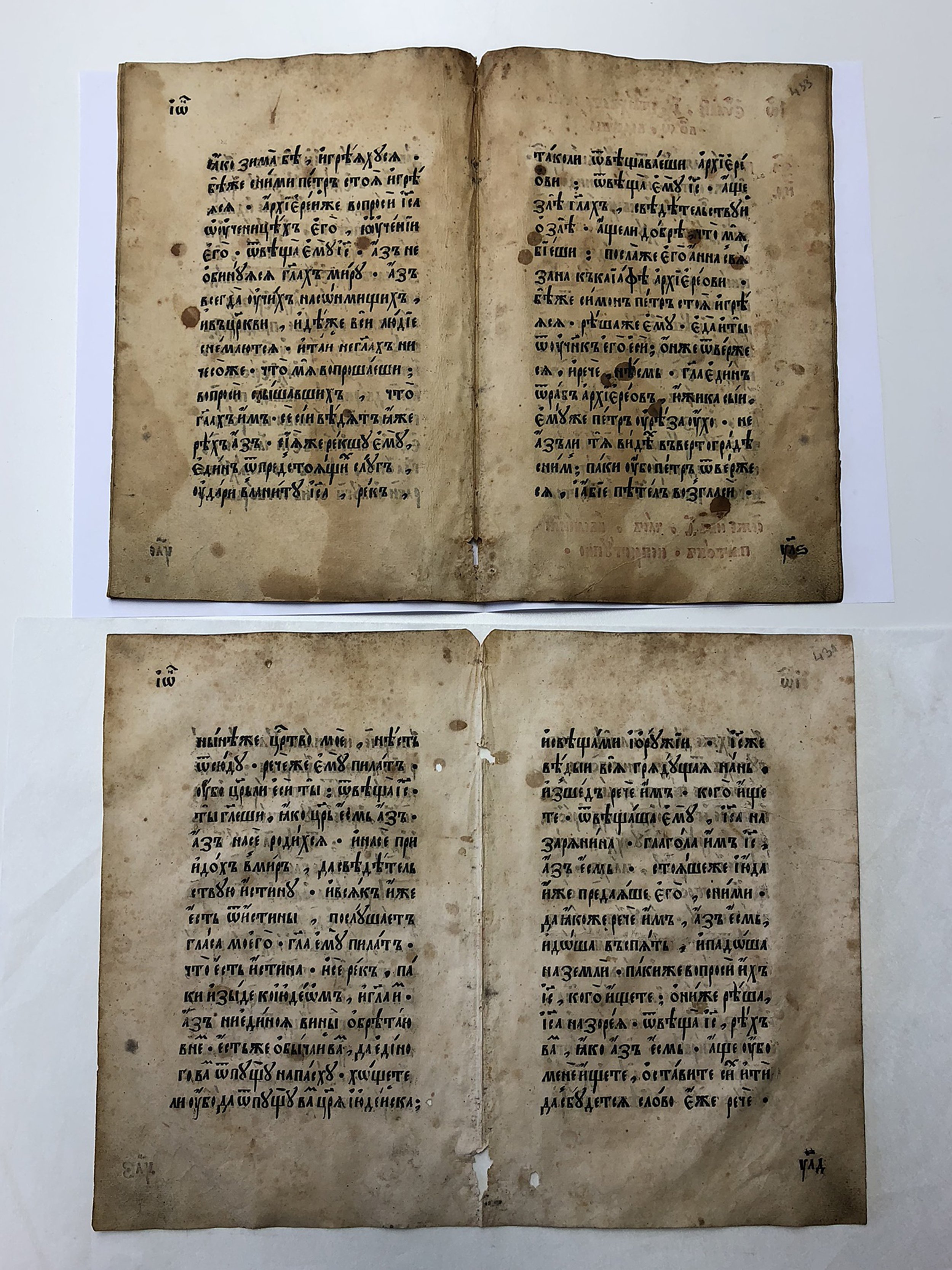

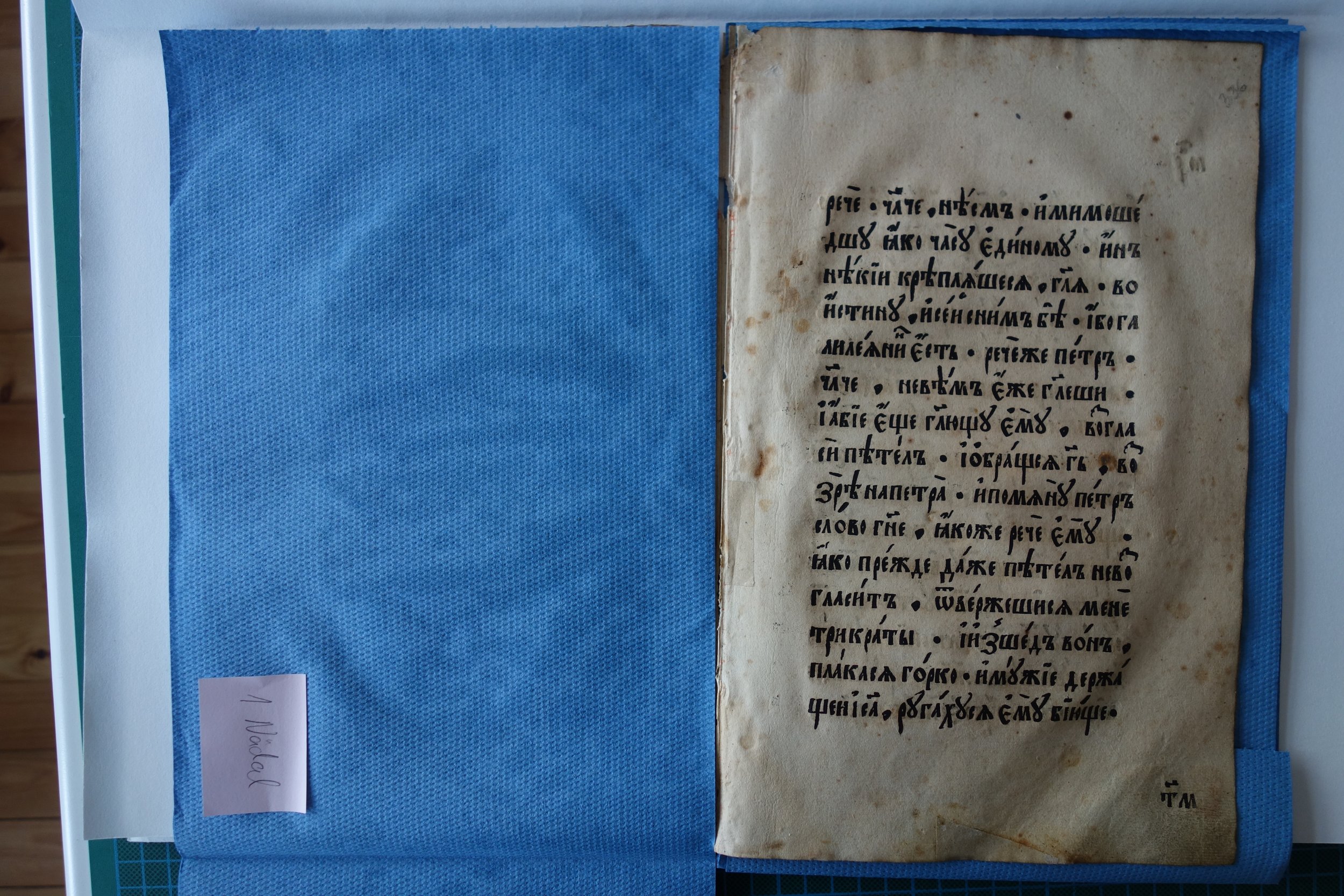

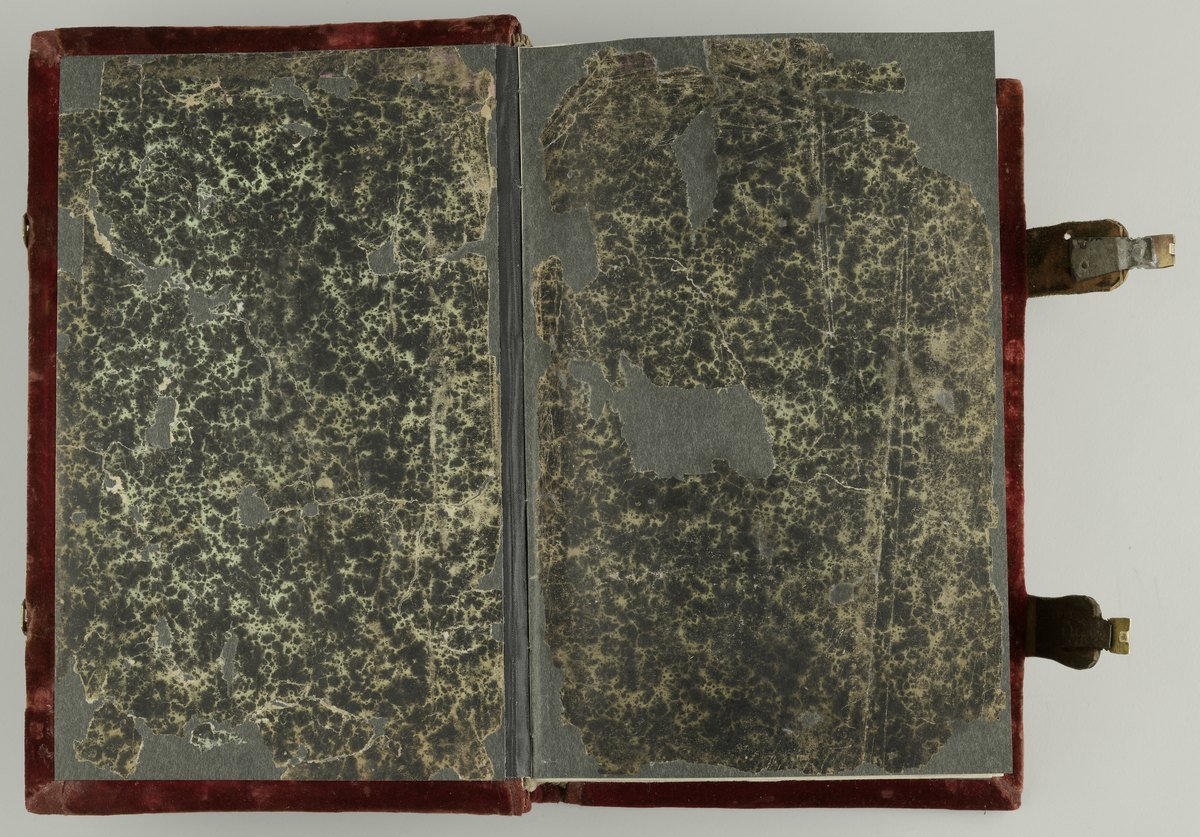

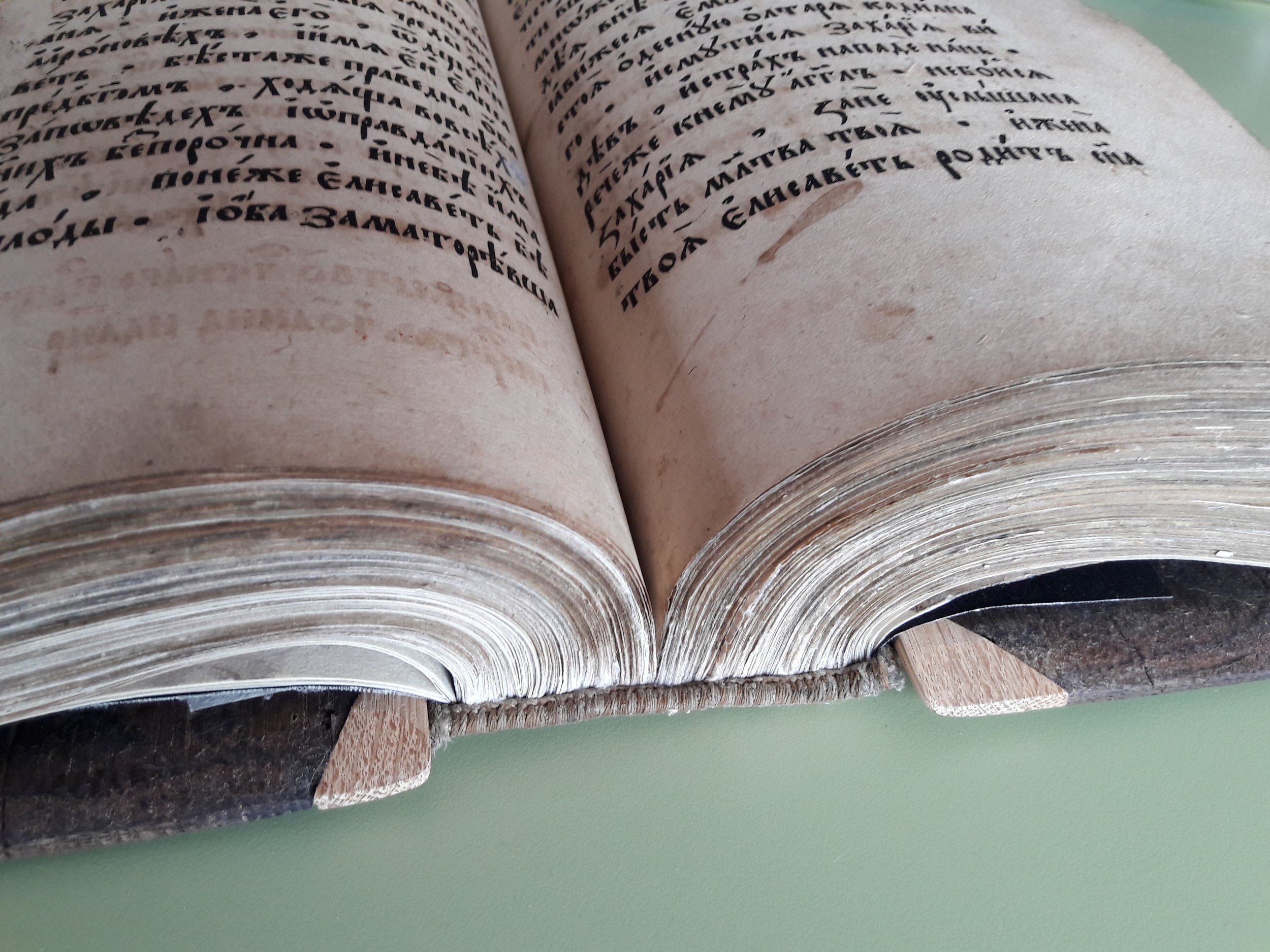

The endpapers of the binding are of greenish and black marbled paper, whose edges have been folded around the first sheet. The joints are not strengthened. [ill 9] The sections, most of which consist of four folios, have been sewn on five linen cords. Initially, the sections had been sewn on four binding cords fixed on the board with a wooden dowel. The text block has been made of rag-paper with varied thickness. The text in Cyrillic is printed in red and black ink. [ill 10] The sequence of the pages is seen on the recto side. Pages with illustrations and blank pages are not numbered. The colophon of the Gospel contains data on the time and place of printing and the last page has an inscription: Kniga Prestolnoe Evangelie…[ill 11]

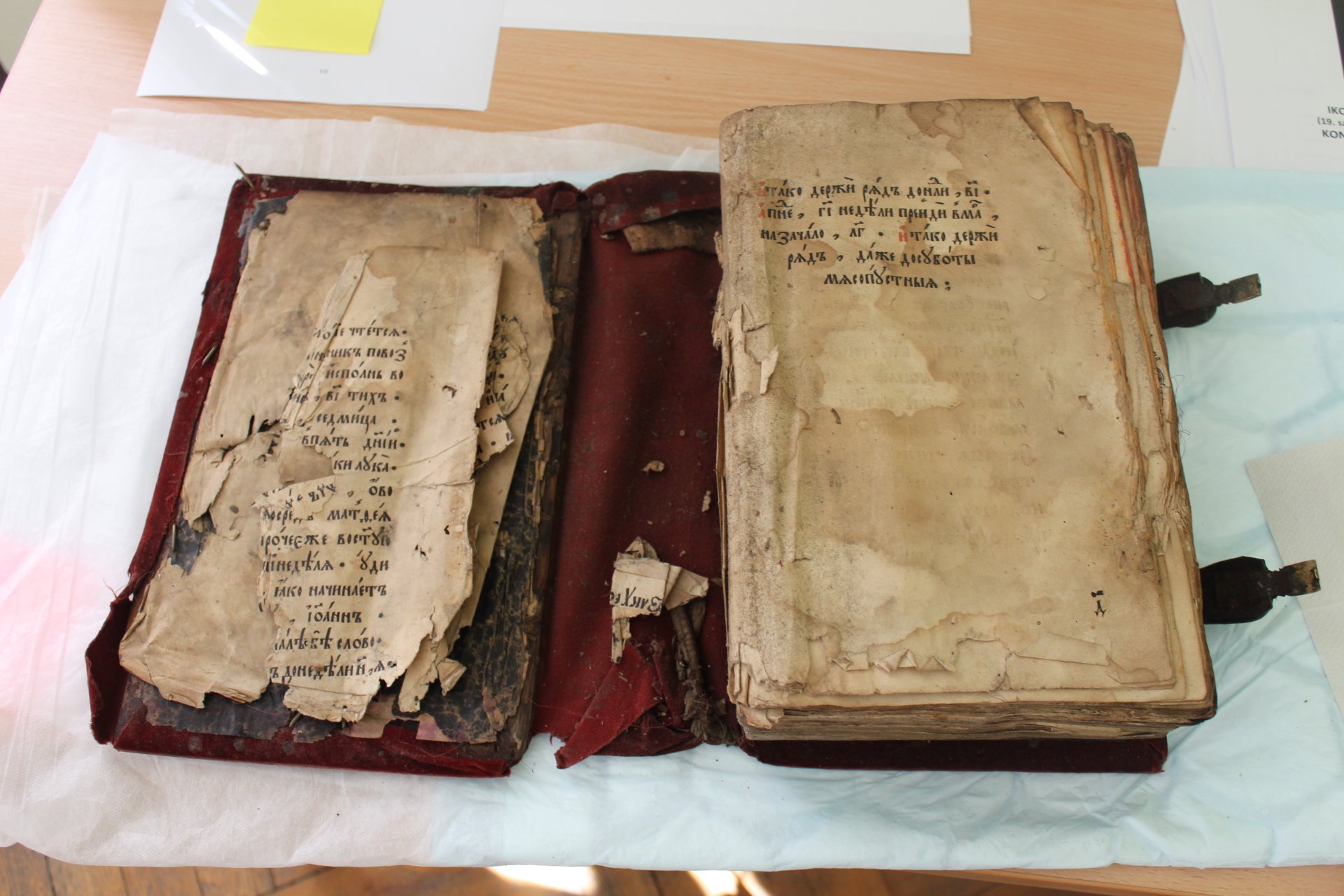

Condition of the Gospel before conservation

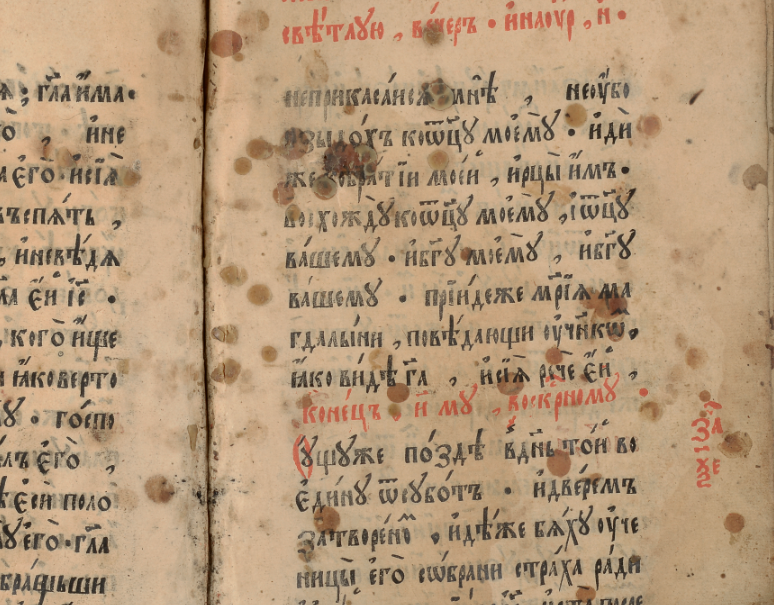

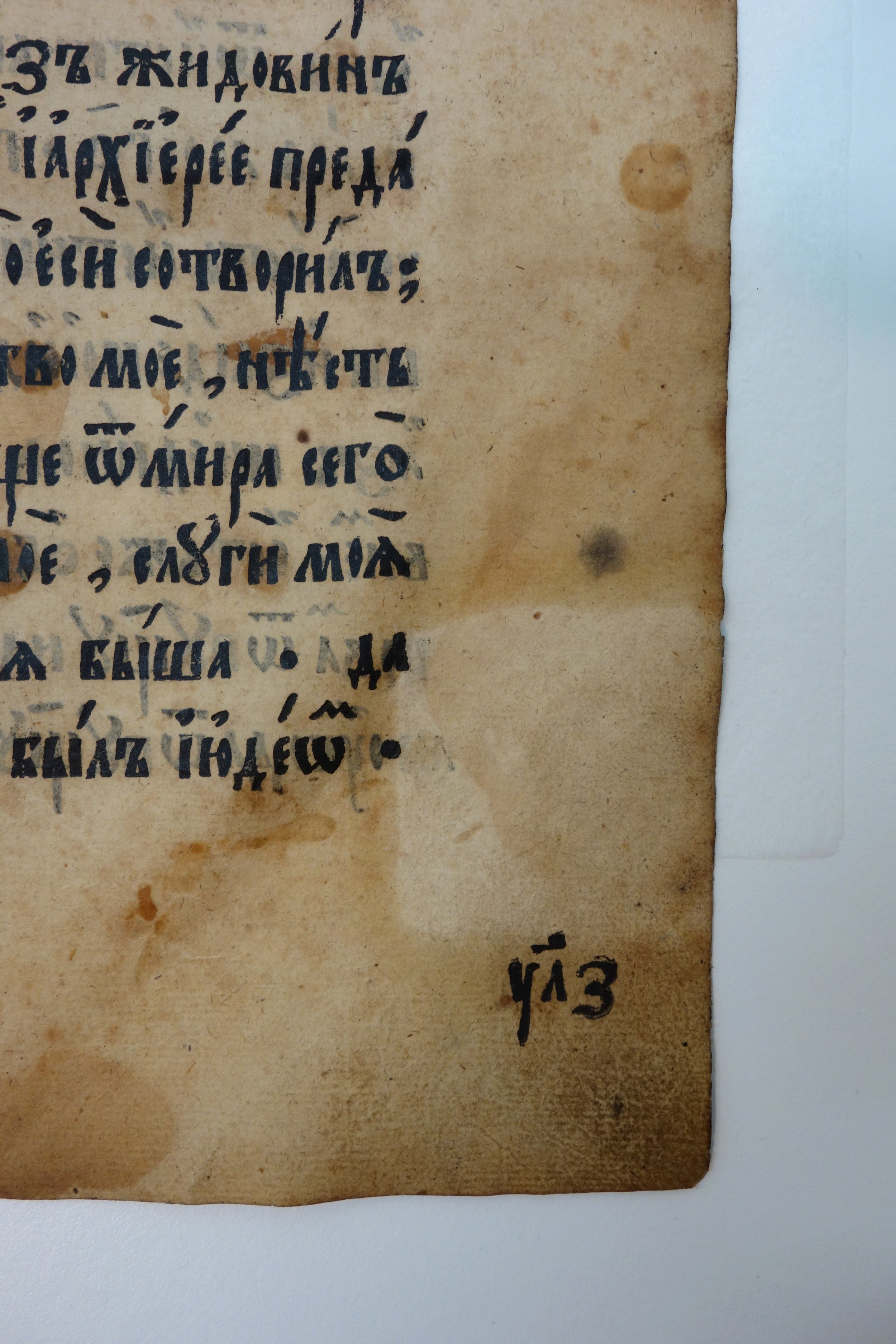

Conservation could begin after lyophilization. It became clear that the condition of the book had not been good even before it was damaged by the extinguishing water during the fire. The block had been damaged by moisture and the paper due to mold. [ill 12], [ill 13] Numerous wax stains throughout the binding had made the paper translucent and fragile. [ill 14] In addition the book had been soaked in some kind of oil with strong odour. Some pages were loose. Still several paper patches indicated that people had formerly attempted to take care of the sacred book. Some of the repairs had been made with rag paper quite similar to the original material [ill 15], others however, with thin wood-cellulose paper that had caused new tears in places. Occasionally the missing text had been carefully restored by hand. [ill 16] During the previous rebinding of the book quite many repairs had been made on the spine of the folios and they had become loose now due to moisture damage.

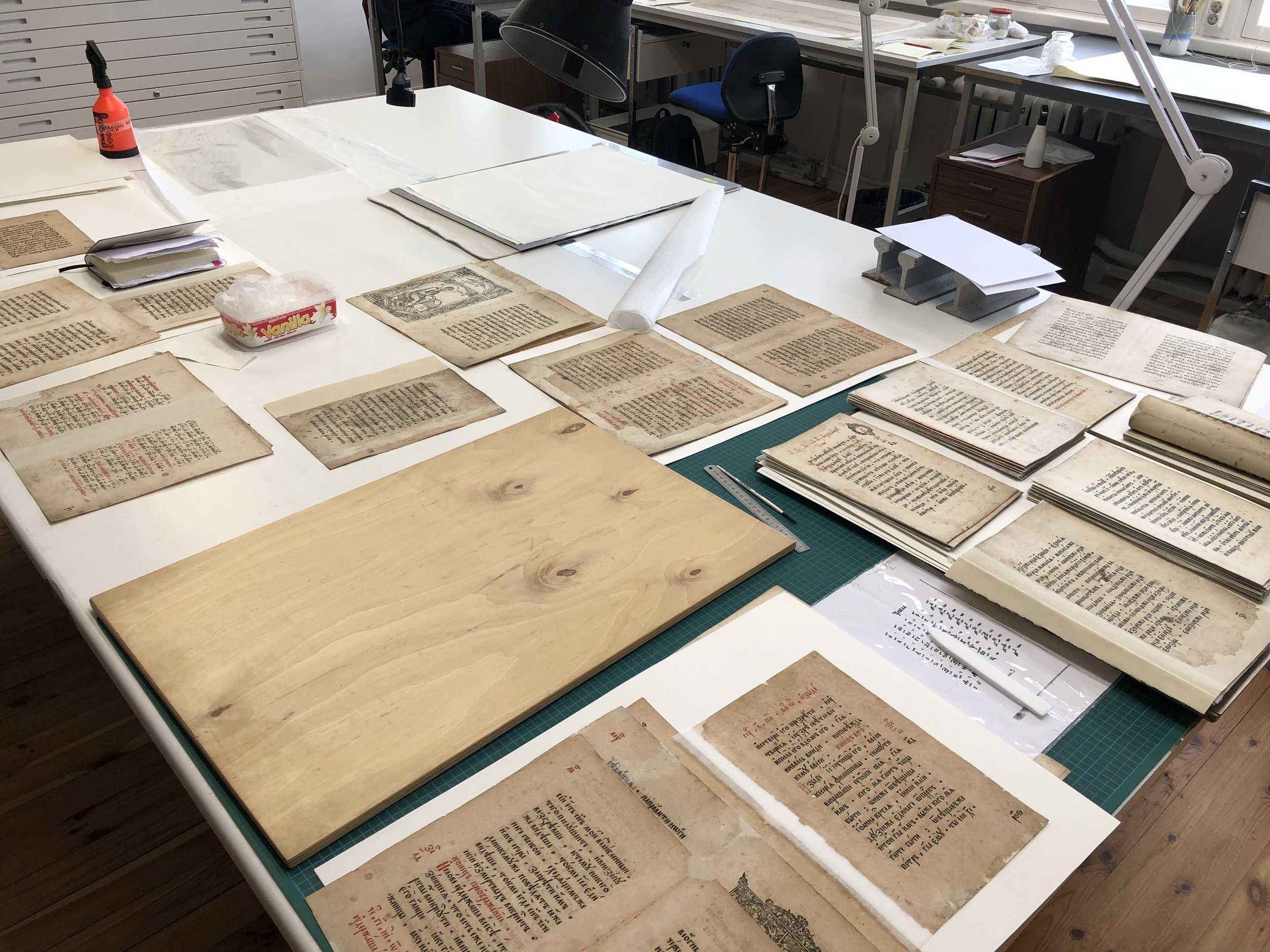

Owing to all these damages it was decided to conserve the binding entirely. [ill 17] The block of the book was dismantled and each folio was treated separately. After that the wooden boards, their covering fabric and metal parts were conserved.

Conservation of the text block

In addition to the general time-consuming conservation process, the removal of wax and oil became a problem. Mechanical cleaning with the help of a scalpel seemed to be the best way to remove drops and stains of wax. Two different ways were tested to remove oil from the paper. First, we attempted to clean the paper with hexane compresses. (12)

The test was made on a sheet in three different places and on an area of 2x3cm. Filter paper with some drops of hexane on it was placed underneath and onto the area of testing. Then the area was covered with plastic and a weight. The compress was in place for 5 minutes. When the filter paper pieces were removed, nothing seemed to have changed, but in about a minute the area became considerably lighter and less translucent as well. [ill 18] Welcoming the good result we processed the whole sheet in the same way and were successful again. [ill 19]

Immediately after processing the sheet with hexane, it was washed in water. We compared the amount of discolouration leaching out from the sheet. The paper processed with hexane yielded considerably more yellow tint than the unprocessed one.

Despite the good result it was still decided to give up large-scale hexane processing, as the health hazards were too threatening. Thus, hexane was used only in case of single bigger wax stains. Searching for a more health-protecting solution, the conservators noticed that the sheets placed singly in between the filter paper had generated lots of oil-spots on the covering paper even without any weights on. Then the idea was born to place all the sheets one by one in between filter paper and apply slight pressure for mechanical removal of oil from the paper. [ill 20] Filter paper was changed several times within the next months. Quite often at first when plentiful oil was extracted and less frequently afterwards, when oil-detachment slowed down. The process was finished when no new oil-spots appeared on filter paper. As a result, the sheets were considerably stronger, less translucent and did not have an unpleasant smell.

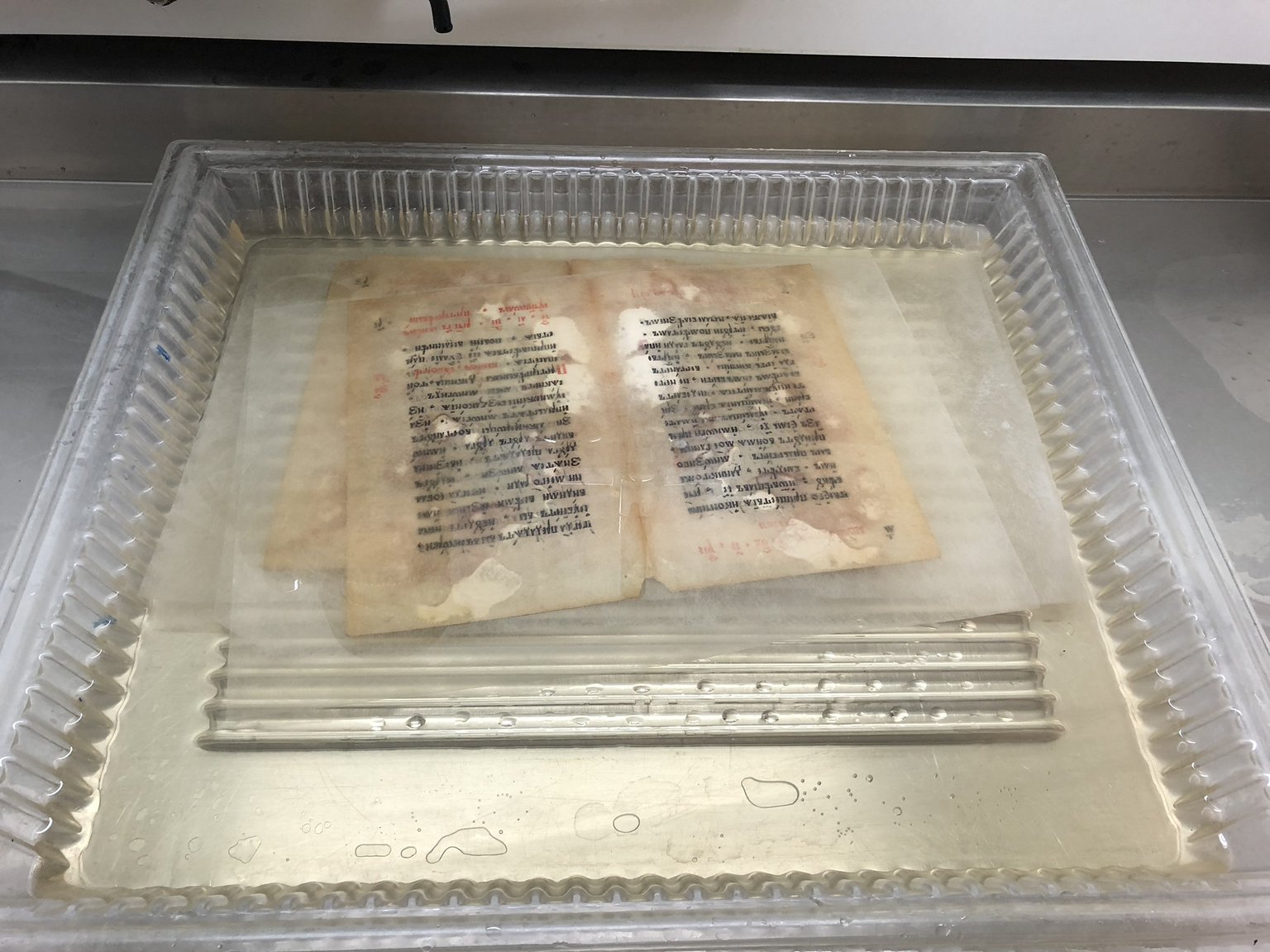

Oil removal took months and after that washing could start. As several sheets were still fragile, it was decided to wash them within Hollytex bags. Every sheet was stitched (using long stitches) in between two layers of Hollytex. It was time-consuming but it actually made the washing process quicker. [ill 21] Only a few fragmentary sheets were washed on the vacuum table. The pages that had been carefully repaired and rewritten by hand in the past, were left latest. It was decided right at the beginning that the most interesting earlier repairs which were not harmful for the binding, would be preserved. The ink used for making hand-written repairs was also tested for water sensibility. Different kinds of ink had been used on both sides of the pages and they all proved to be water-sensitive. Considering that, it would have been harmful to wash them on the vacuum table, where the ink could disappear or ‘emigrate’ onto the other side. It was also difficult to foresee how the glued-together sheets would react getting wet. Due to that it was decided to only dry clean and, when necessary, fix and support the old repairs on the sheets mentioned above.

The next step was sizing and repairing the rest of the block. For sizing 0.5% gelatin solution was applied on the paper with a brush. Wheat starch paste was used for mending. Most of the sheets were repaired by hand on the light-board. Japanese paper of different thickness – 5g/m2, 9g/m2 and 11g/m2 – was used. Bigger losses were filled with rag paper of suitable color and thickness. As several damages were found throughout the text block, it was essential to observe the thickness of the repairs in order to preserve the original dimensions of the block. It was especially important on the spine of the block, as almost all folios needed repairing at the folding line. When losses were not extensive, rag paper fillings were not used, as Japanese paper sufficed. At the bottom foot of the binding the paper was fragile, especially where mold damage occurred. These areas had to be lined with Japanese paper 5g/m2.

Some of the sheets were severely decayed and fragmented and leaf casting method was considered the best solution for repairing them. As it was not possible to do it at the Conservation Centre Kanut, we used the leaf casting machine at the conservation department of the National Library of Estonia [ill 22]. This method made it possible to fill in extensive losses quickly and to restore the format of the sheet. [ill 23] After the sheets had been dried in the press their extra edges were trimmed and the folios were folded back into sections. [ill 24], [ill 25] Paper conservation was done by Grete Ots and Kaisa Milsaar.

Conservation of the velvet textile

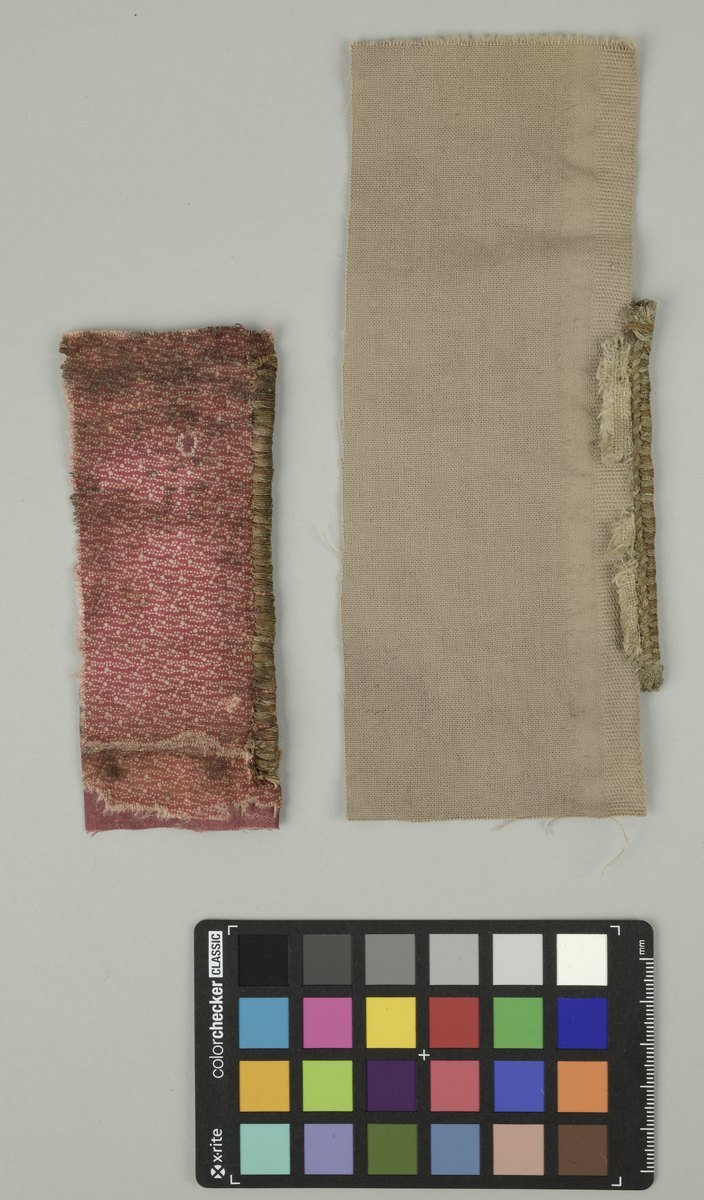

The wooden boards of the Gospel had been overlaid with uniform covering of red silk velvet on cotton warp. The material had visible damage. [ill 26] It was decided not to replace the fabric with a new one, but to conserve the old.

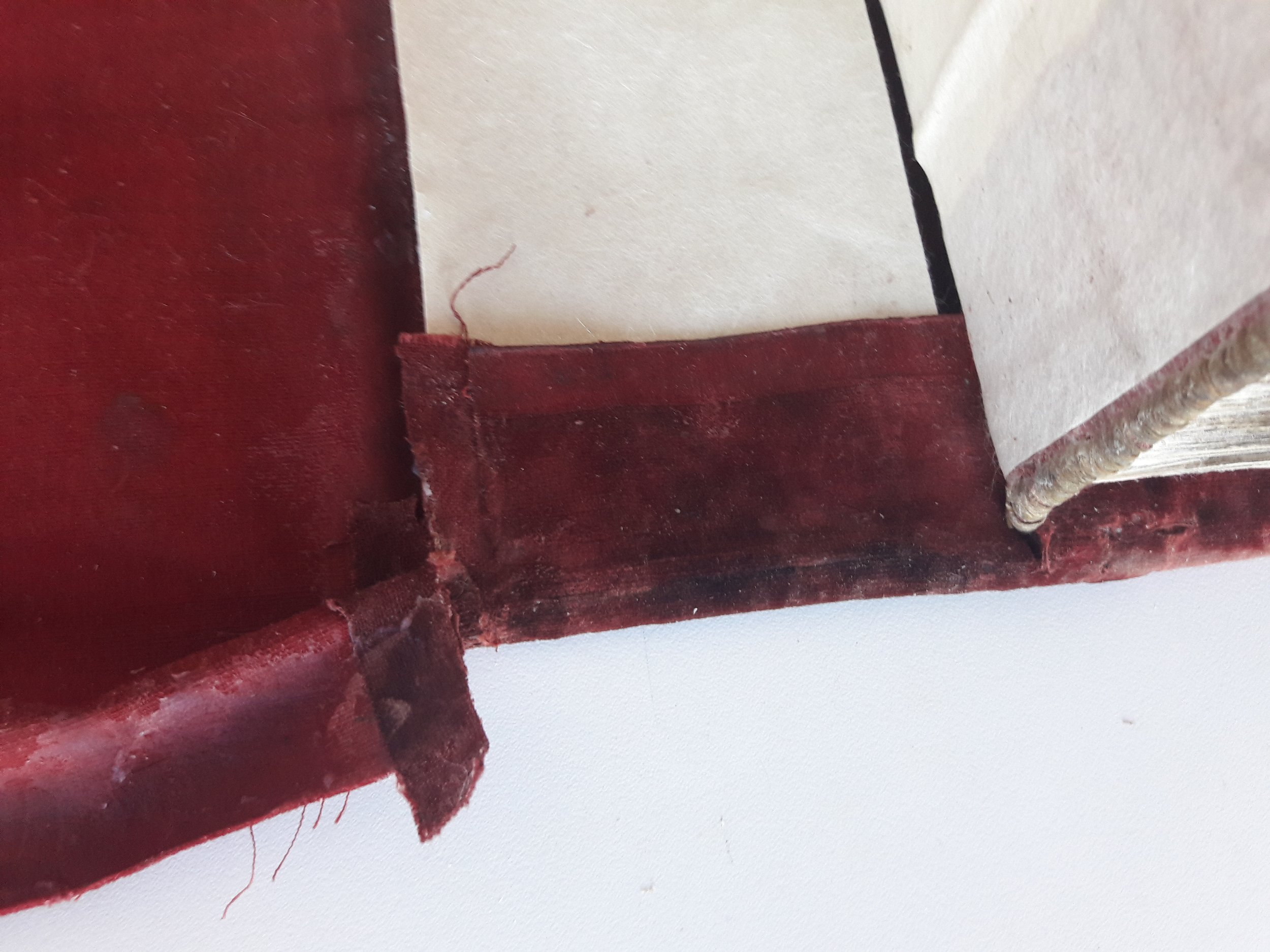

On the inside the fabric contained wood-dust, oil and glue spots, while on the outer side it showed traces of wear, some tears as well as spots of oil and wax. The latter were especially numerous on the lower part of the back cover. [ill 27] The color had faded, as was shown by the original sample that could be seen underneath metal attachments. At the back of the book and breakpoints of outer edges the velvet material had worn down and was missing in places, so that the cotton warp was bare. There were some rips, too. The dirt layer on the soiled edges was thick and compact, obviously a mixture of candle wax, oil and sebum from hands. The fabric had lost most of its initial elasticity and potency. As the metal attachments had been fixed with nails numerous small holes had been left in the fabric.

First treatment applied was dry-cleaning with mini-tipped vacuum cleaner. Simultaneously, thinner candle wax spots that were not firmly attached to the fabric were removed with a thin metal spatula. In order to cleanse the fabric from oil and wax residue it was placed on a wad of filter paper and processed with cotton swabs moistened in White spirit. The latter made the spots softer and forced wax into filter paper. The procedure was repeated until filter paper remained clean. The same technique was used for cleaning the dirt on the break points of the covers. The general cleaning of the fabric was carried out on the suction table with low vacuum pressure. This way the fabric retained its initial size and later stretching was not necessary. The tears were repaired with similar-colored silk on the reverse side of the velvet covering. [ill 28] The conservation of textile was carried out by textile conservators Ruth Paas and Anna Zhenkevitch.

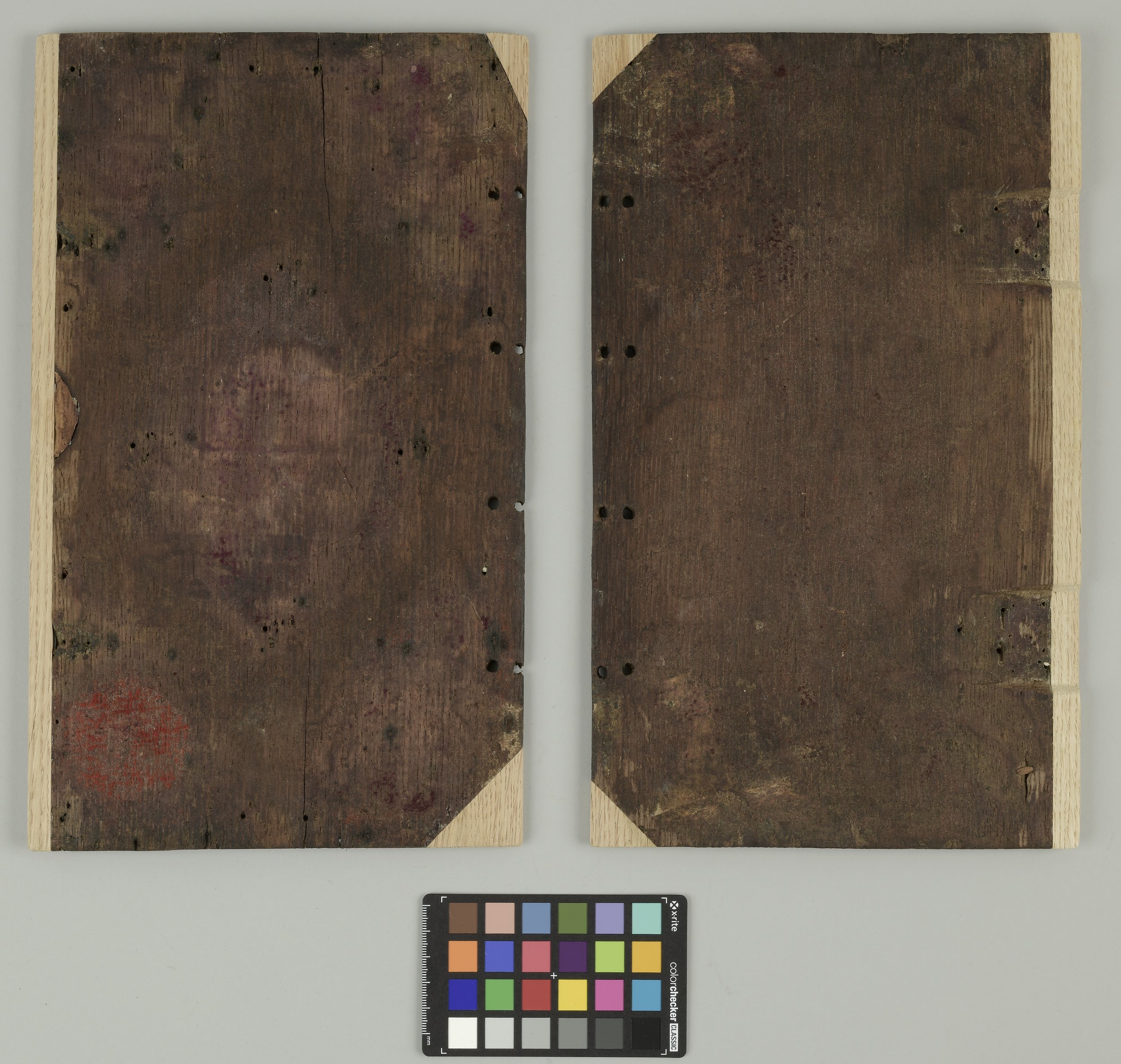

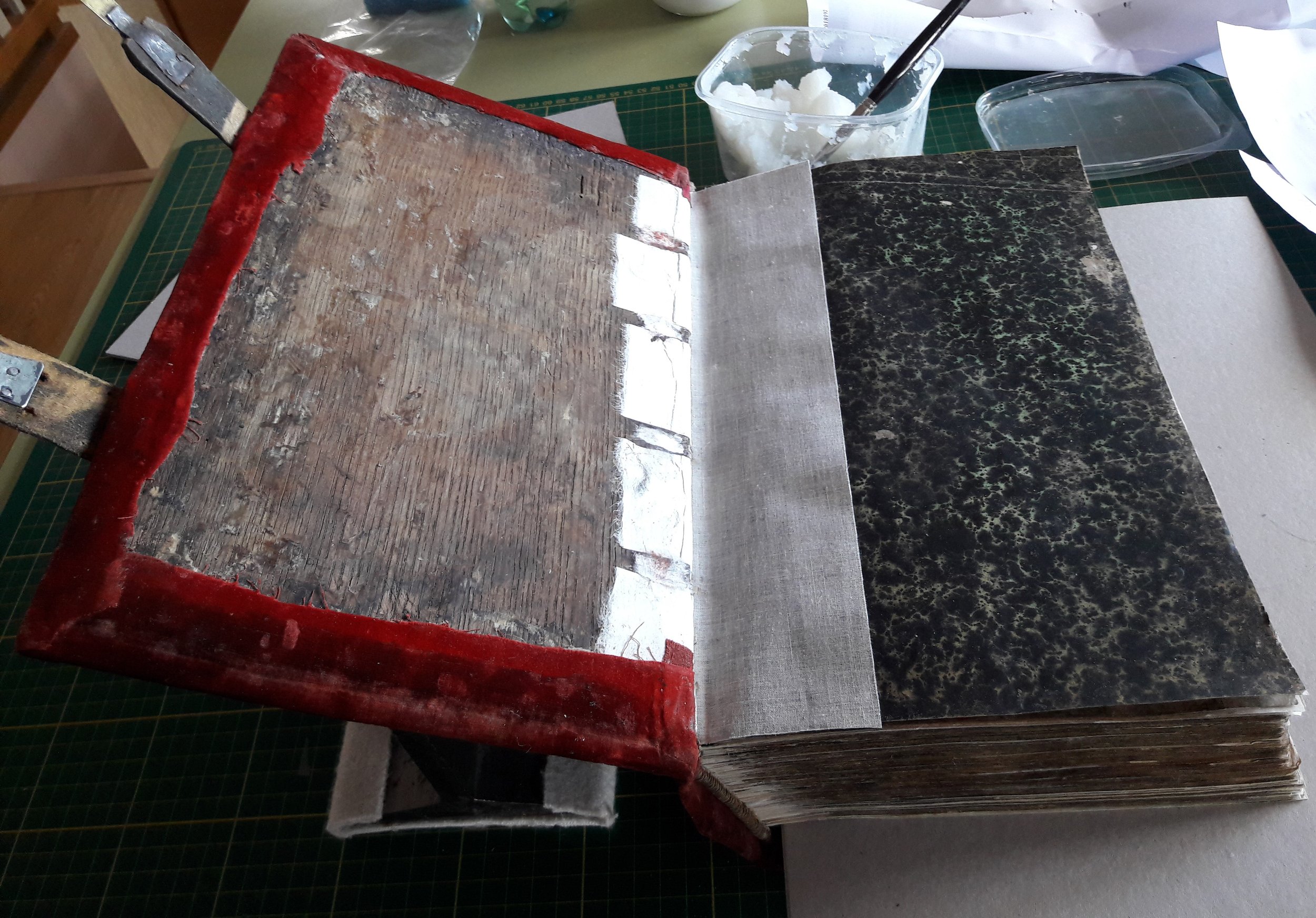

Conservation of the binding

Prior to starting conservation of the oak boards, decorative plaques and the fragile velvet textile had to be dissembled. First of all, the 2cm long copper nails that were fixing the plaques to the boards were mechanically removed. The ends of the nails had been turned back. The velvet covering was removed carefully, separating it first on the verso and then on the recto side. The wooden boards were dry-cleaned with a soft brush. The damaged edges and corners were milled and moulded on the milling cutter, new parts were made and fastened with the glue Titebond. (13) [ill 29] Wooden boards were conserved by Mart Verevmägi.

Later the new wooden material milled for edges and sharp corners was polished by hand and with sandpaper to make the details smoother and rounder and to avoid tearing the fabric when covering the boards. Decorative plaques were dry-cleaned with a brush and then washed in warm soapy water. The final cleaning was made with a cotton swab moistened in acetone.

The marbled end papers were removed from the boards mechanically, washed in charcoal-filtered tap water and sized with 0.5% gelatin solution. [ill 30] They were lined with tissue paper on the verso side and then pasted onto greyish-black Japanese paper Satogami; wheat starch paste was used as adhesive. [ill 31] As rather heavy metal plaques were fixed firmly to the board and its lifting could endanger the condition of the joints, a 6cm-wide black calico strip – the book binding cloth joint – was added to make the joint stronger. The cloth joint together with the folded edge of the first section was turned around the endpaper and pasted on the edge of the second section. Wheat starch paste was used.

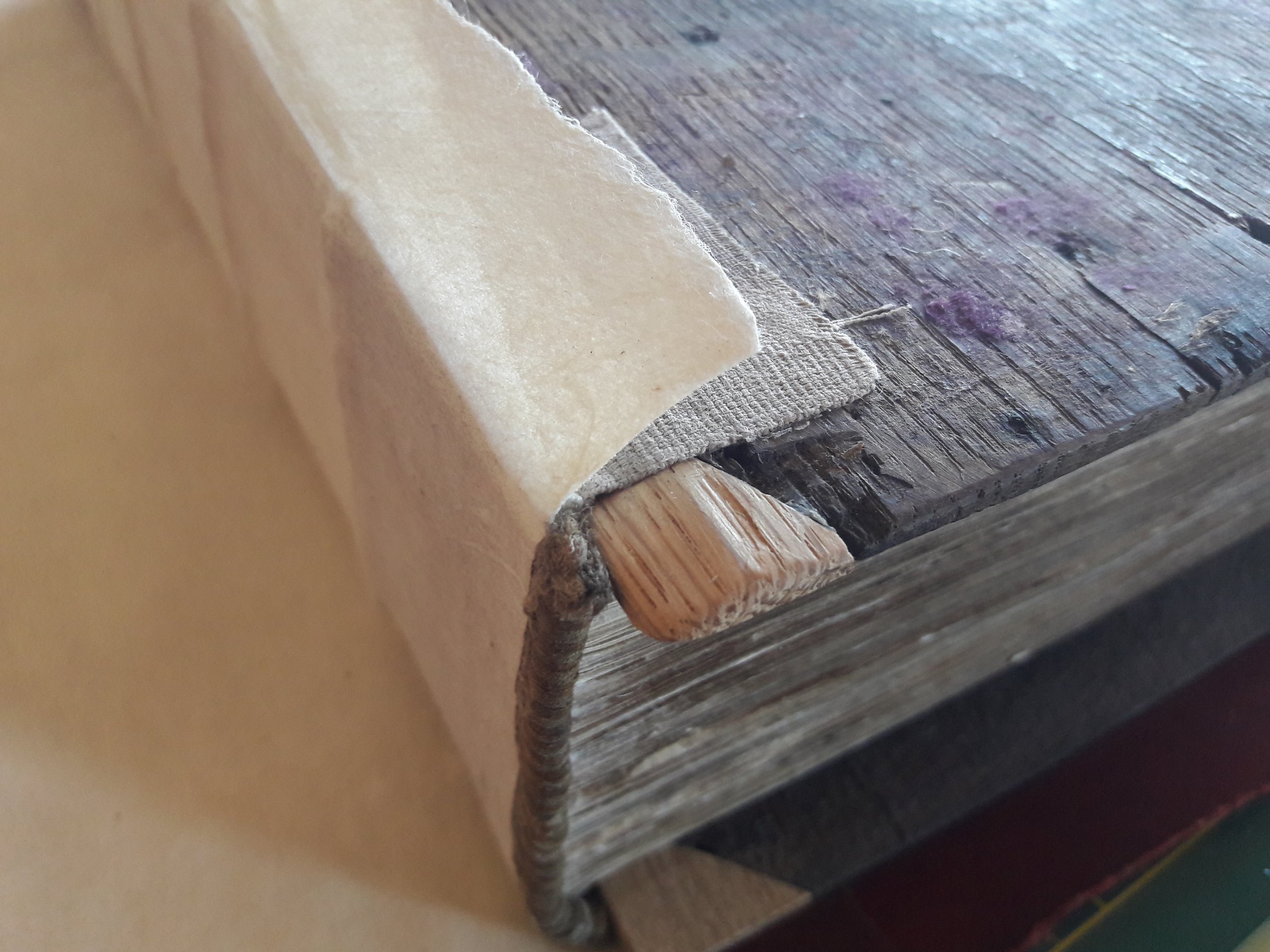

Next the sheets were collated and strips of Japanese paper were pasted on single leaves in order to stick them to the edges of double leaves. This helps the leaf to open properly. In the course of the collating and pasting process, smaller tears were repaired and loose parts were fixed. Thereafter all the leaves were placed in between the boards of the binding press for a week. A binding frame was prepared for sewing the binding. Four double linen cords were made. [ill 32] The sheets were sewn with linen thread, one by one in pretzel-stitch. It was diligently observed that one side of the block should not become thicker than the other one. Changes in thickness of the text block were caused by paper damages that had occurred mostly in its upper part. Thus, due to paper repairs it had been a bit thicker already before sewing.

Next the first strengthening with Japanese-paper (30g/m2) was made. To that aim a strip of paper with the same width as the spine of the block was pasted on to the spine. Then Japanese paper strengthening strips were pasted in between the cords on the back of the block, so that their ends reached 4-5cm over its width. These loose ends were later pasted upon the inner sides of the wooden boards in order to strengthen the connection between the boards and the block.

The two-colored textile-covered headbands sewn on the core were cleaned and the loose ends of thread were fixed. As initially different strengthening textiles had been used it was necessary to line them with cotton and linen fabrics. The headbands were fixed with wheat starch paste onto about 5cm length of the block’s spine, the ‘ears’ left on the outer side of the wooden boards. [ill 33], [ill 34], [ill 35], [ill 36]

The last layer of Japanese paper pasted on the spine was 4cm wider than the block.

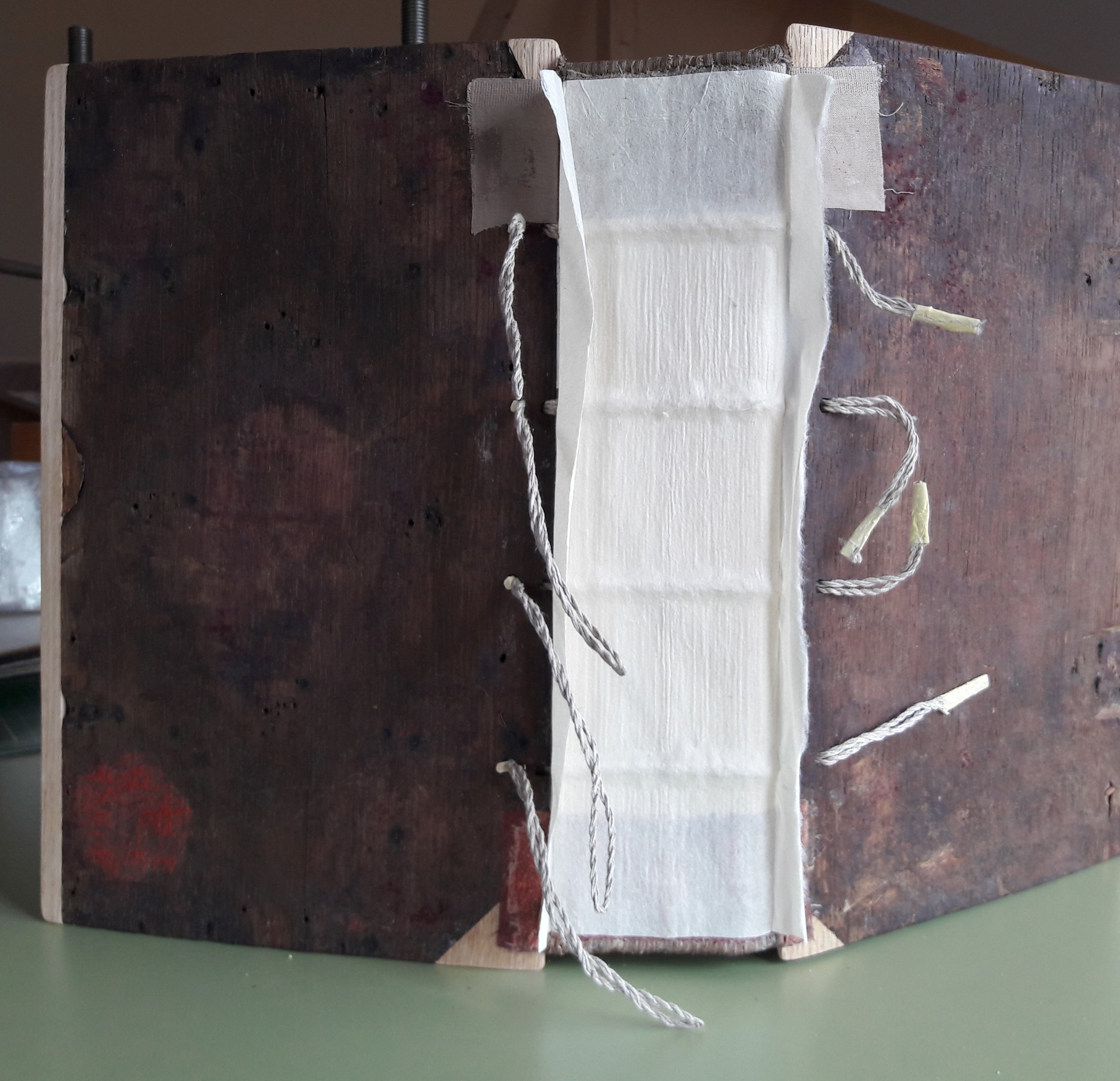

The ‘ears’ of the five Japanese-paper strips on the spine of the block were pasted on the inner sides of the boards. When the paste was dry, it was checked whether the boards were at the right distance from the block. Then paper tape was wound round the ends of binding strings to make it easier to pull them through the tunnels. The cords were pulled through the double holes. The cord entered the first hole on the outer face, travelled in a few-millimeter deep channel in the inner face of the board, and continued to the second hole exiting again on the outer face of the board. The cord was plugged with a dowel. The holes were first filled with Evacon glue. (14) [ill 37], [ill 38] If only dowels were used, one of them might still move and the strings could have tension or backlash in them. The board might keep moving at its upper or lower edge. When the boards and the block had been solidly fixed, the next task was attaching the clasps, the covering fabric and the bronze plaques.

Conservation and mounting of the clasps

The clasps were softly cleaned with steel wool of fineness 0000. One of the hasps had a metal tablet that was rusty and had to be replaced. The new metal tablet was made and riveted by Helmut Välja. All the clasp details were fixed with copper nails just like they had been initially attached and it was done before it was covered with velvet fabric. First the leather strap was fixed in between the hasp and the restored fastening plate. Then the catch plates were fixed on the front board with tiny nails. [ill 39] Finally the leather straps were fastened on to the back board, carefully checking the tension in the hasps. [ill 40]

Covering the boards with fabric

As the leather straps had been fastened straight on to the wooden board, slits to accommodate them had been originally cut in the velvet fabric. When the conserved velvet was pasted on to the boards the backing material had to have similar slits. Next, the edges of the fabric were fixed with wheat starch paste and turned over the boards. On the outer sides of the boards the fabric was kept free of adhesive. On the corners the fabric was slightly over-folded to prevent opening when drying up. Close to the joint a slit was cut to make it possible to paste the turned part of the fabric onto the inner side of the board. These slits were 2cm long, whereas a 1cm wide part of the fabric on the very edge was not cut open. [ill 41]

The spine piece was made of thicker and stronger double Japanese paper to provide some body to the back, at the same time avoiding rigidity. The spine piece was attached to the fabric by pasting only the turned-back parts of the fabric. [ill 42]

The correct position of decorative plaques had to be determined before they could be attached. When the bigger holes in the boards corresponded to the required ones, they were provided with wooden dowels and a minimal quantity of Evacon glue. Then the metal insulating board was placed in between the block and the board and small holes were drilled (1mm drill) into the board. The five bronze plaques were fastened with copper screws. [ill 43], [ill 44], [ill 45] The one on the right could not be fixed properly – a 3mm high airspace appeared under a corner. This was caused by a catcher plate on the front board. The solution was to cut out a 3mm thick, 4x4mm cardboard piece, that was covered with red silk fabric and glued onto the back of the plaque. [ill 46]

To smooth down the uneven surface of the inner side of the board and the thickness of the velvet fabric, a thinner greenish-brown cardboard was pasted with wheat starch paste. This done, a calico cloth joint was pasted on the inner sides of the boards. [ill 47] The paste down– a part of the endpaper–was pasted down to the inner side of the board and lined with archive cardboard. This made the board smoother and levelled the rise caused by the velvet covering. The tension in the joints of the closed clasps was carefully regarded to prevent them from opening on their own. The last touch was pasting the original doublures of conserved and lined marbled paper back onto the inner sides of the boards. Tulvi- Hanneli Turo was the conservator of the binding.

The immensely valuable Gospel rescued from the burning chapel has been restored in its original shape. [ill 48] The damage caused by extinguishing water has been removed and the block, covering textile and parts of the book’s construction have been conserved. It is now possible to study and to exhibit the Gospel again. The best way to do it is to place the binding on a suitable book cradle. [ill 49] The treasure binding has been packed in an archive cardboard box, waiting for the time it would be returned to the island of Piirissaar.

Estonian paper and binding conservators have worked on the bindings belonging to the Old Believers before. At the beginning of 2006 the civil parish of Kasepää arranged a public procurement for conservation and restoration of 172 books and manuscripts belonging to the Raja Old Believers’ Congregation. Back-up copies were included in the procurement. The Conservation Centre Kanut won the public procurement and launched the project in 2006-2007. Working on the project gave the conservators an opportunity to study the Old Believers’ history and their valuable literary heritage. These publications include some 16th and 17th century bindings in the Cyrillic, all of them rare and valuable indeed.(15)

REFERENCES:

References:

Kristina Aas. Icons of the Piirissaar chapel – from the fire up to the restoration. – Renovatum Anno 2019/2020 https://renovatum.ee/autor/piirissaare-palvela-ikoonid-polengust-restaur... (accessed 09.11.2020)

Eve Keedus, Heli Märtin, Liis Turnau, Jaan Lehtaru, Tulvi Turo, Silli Peedosk, Tiia Nurmsalu, Urve Kolde. Salvaging and Conservation of Fire-Damaged Prayer Books of Piirissaare Old Believers Congregation. – https://www.renovatum.ee/en/node/485

Alar Läänelaid, Tulvi-Hanneli Turo. Vanausuliste püharaamatu kaaned tõid üllatava avastuse. – https://heureka.postimees.ee/679425/vanausuliste-puharaamatu-kaaned-toid..., https://www.horisont.ee/arhiiv-2019/Horisont-4-2019.pdf Alar Läänelaid, Tomasz Ważny (2017) Re-bound book covers from the island of Piirissaar, Estonia, The Baltic Journal of Art History. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2017.14.07

Jaan Lehtaru. Piirissaare palvemaja raamatute päästmine ja konserveerimine (Rescue and conservation of books belonging to the Piirissaare chapel) https://blog.ra.ee/piirissaare-palvemaja-raamatute-päästmine-ja-konserveerimine.

Evangeelium. Moskva: PetšatnõiDvor, 30.IX 1633 (1. XI. 7141 – 30.IX.7142) Mihail Filaret 2.4-14, 16-495 1. Printing data in the colophon (1 492-495): the first three leaves in fragments. The 4th leaf engraving (evangelists), head-slats, initials, frames and emblem with crucifix (1 419p). 18th-century binding: red velvet with decorative bronze plaques (evangelists with crucifix in the centre). On page 495p inscription from the 17th century. (Zernova No 99) The last page has the inscription: Ќнига Престольное Евангелие. Prinadležit Želatšenskoi obšinõ za No 31. Predsedatel, sekretar S. Kolbõkin. 1925vo godaJanvar 30vo dnja. A.S. Zernova. Knigi Kirillovskoi petšati izdannõe v Moskve v XVI-XVII vekah. Svodnõi katalog. Moskva, 1958. The bibliographic record of the Piirissaare velvet treasure binding was compiled on 10. 11. 2020 by Larissa Petina.

Register of the memorial No 21742. https://register.muinas.ee/7.

Nadežda Morozova. Eesti vanausuliste kirjalik pärand. (Written heritage of the Estonian Old Believers) Tartu, 2915.

Irina Külmoja. Eesti vanausulised, nende kombed ja keel. (Estonian Old Believers, their customs and language). – https://www.sirp.ee/s 1-artiklid/c21-teadus/eesti-vanausulised-nende-kombed-ja-keel/

Heige Peets. Materjalide märgumine ja kuivatusmeetodid. (Wetting and Drying Methods of Various Materials) – Renovatum Anno 2004, pp 76-78. – https://evm.ee/uploads/files/renovatum 2004.pdf (accessed 09.11.2020)

The object passed the following warming up cycles: 1. Pressure 4 mbar – Ir temperature + 100 º – min. duration 600 minutes; 2. Pressure 3 mbar – Ir temperature + 120 º – min. duration 240 minutes; 3. Pressure 2 mbar – Ir temperature + 150 º – min. duration 240 minutes

Measurements of the Gospel details: Oak boards – 198x320mm, thickness 8mm, on the edges 3mm. Rounding on the inside of the board 10-15mm. Bronze corner-plaques 90x115mm, the central one 165x140mm. Hasps 52x30mm, leather strap 25mm wide, metal fastening 34x16cm and the catching plates on the front board 28x15mm.

n-Hexane C6H14 is a non-polar solution that dissolves fats, oils and paraffin well. As it does not hold moisture in paper it does not dry it. It does not leave aureoles in the processed paper. As the chemical evaporates quickly, it makes removing spots harder – the solution ‘deserts’ the system before it starts working. That is why compress-method can be recommended. As the chemical istoxic, means of protection and local exhaust ventilation should be used. (Editor’s note.) Heige Peets. Lahused ja lahustumisprotsesid konserveerimises. Loengukonspekt (Solutions and dissolution process in conservation. Notes for a lecture.), 2004 https://evm.ee/uploads/files/loeng13.pd

Cold glue Titebond (Kremer-Pigmente, Germany). Titebond Liquid Hide Glue is the first ‘bone’ glue that needs neither mixing nor heating up. It is very good for restoration of antique and truly old pieces of furniture, but also for making modern furniture and musical instruments. http://www.coloratum.ee/titebond-liimid.html

Evacon R Conservation Adhesive (eva). White water-soluble emulsion, with no plasticizers (eva: ethylen-vinylacetate-copolymer emulsion). Conservation by Design Limited, A Larson-Juhl Company –www. conservation-by-design.co.uk

Urve Kolde, Ave Tarvas, Larisa Petina, Heige Peets. Raja vanausuliste koguduse raamatukogu raamatute ja käsikirjade konserveerimine. (Books and manuscripts of the library of the Raja Old Believers’ congregation) – Renovatum Anno 2010, pp 28–32.https://evm.ee/uploads/files/renovatum 2010 a.pdf