AN INCOMPLETE STORY ABOUT THE CONSERVATION OF THE HAND-PAINTED MAP OF THE PALMSE MANOR

Autor:

Maris Allik

Number:

Anno 2019/2020

Category:

Conservation

It is a rare case when our expectations and the reality concur.

The same is true about the map of the Palmse Manor. The SA Virumaa Muuseumid applied to the Kanut for conservation, aiming to display the map again at its original place – on the wall of the squire’s study. Seems straightforward enough, but in practice it became a rather complicated assignment and it turned out that the conservators were much more provoking than the applicants had expected…

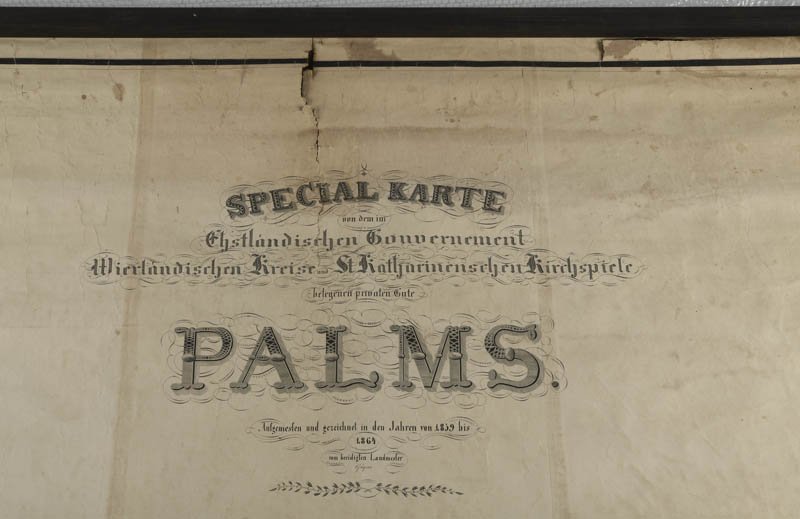

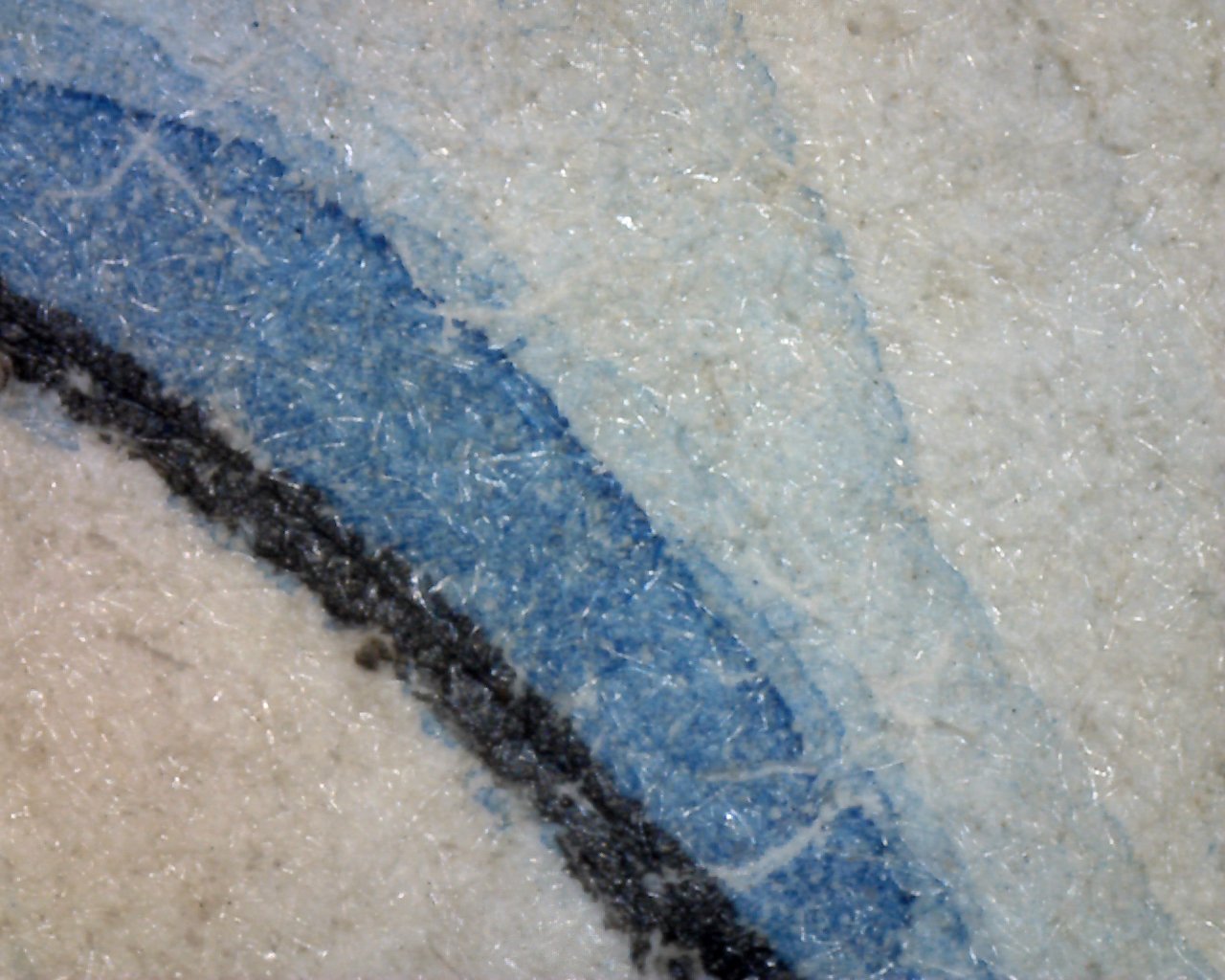

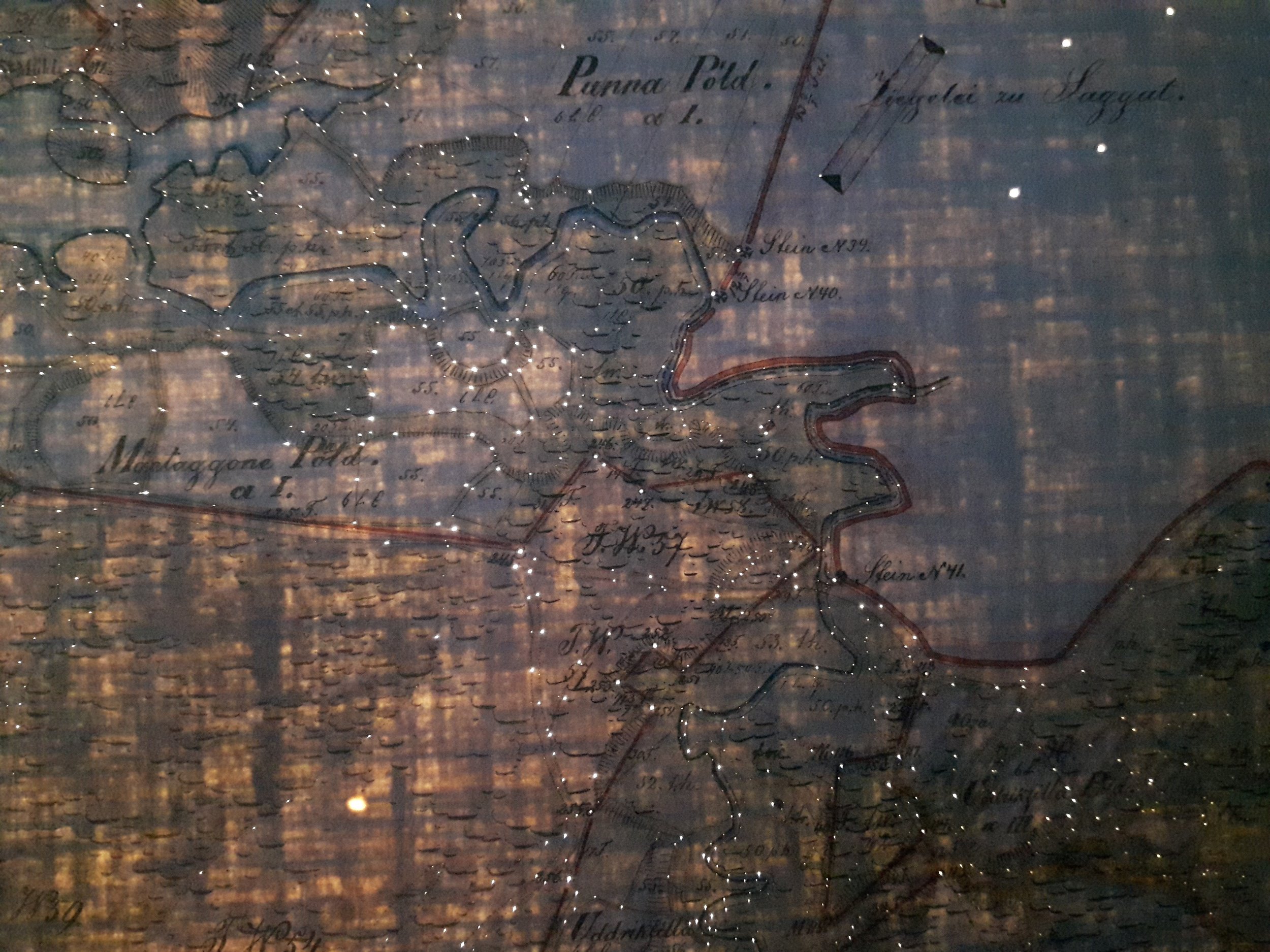

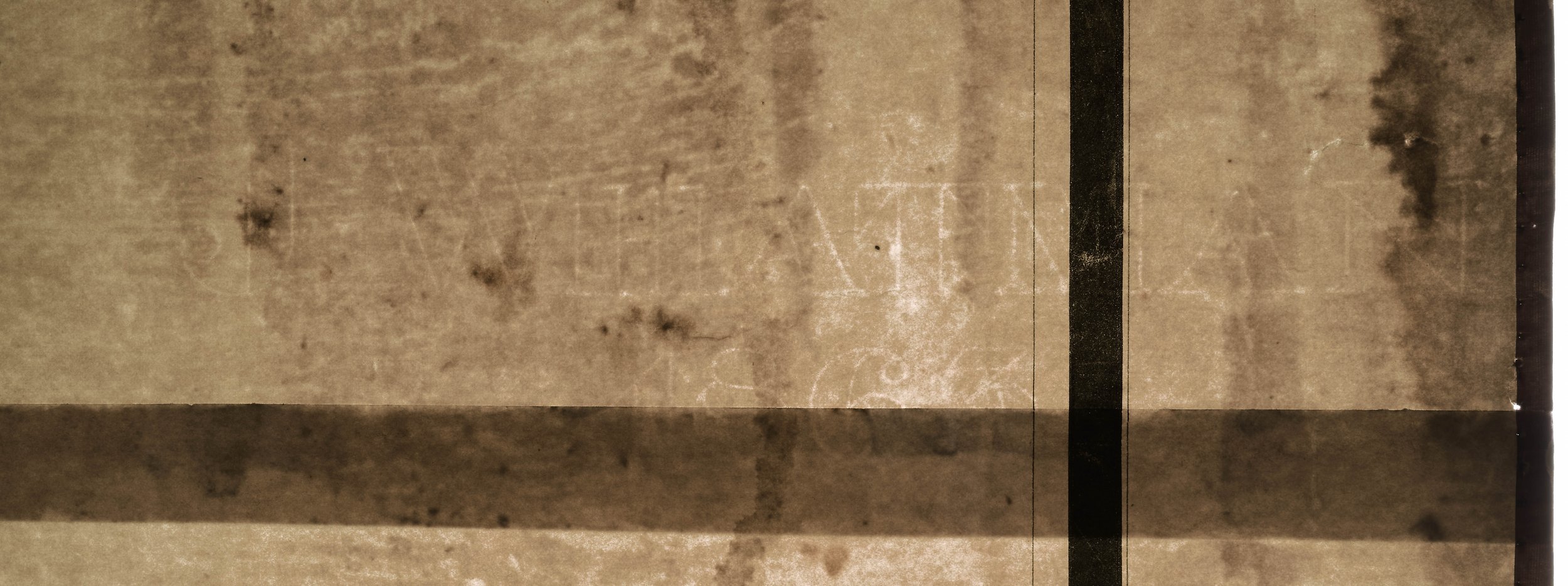

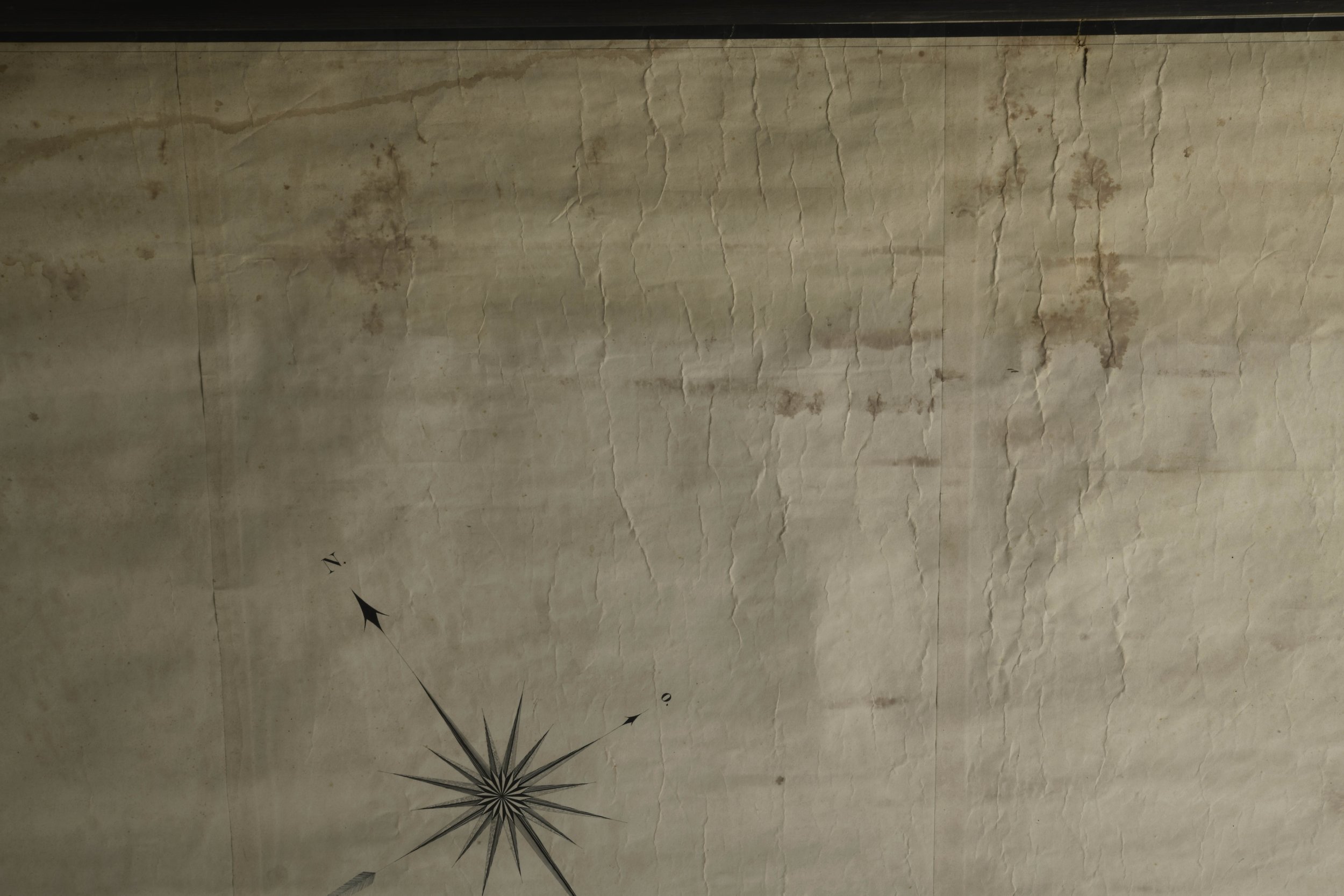

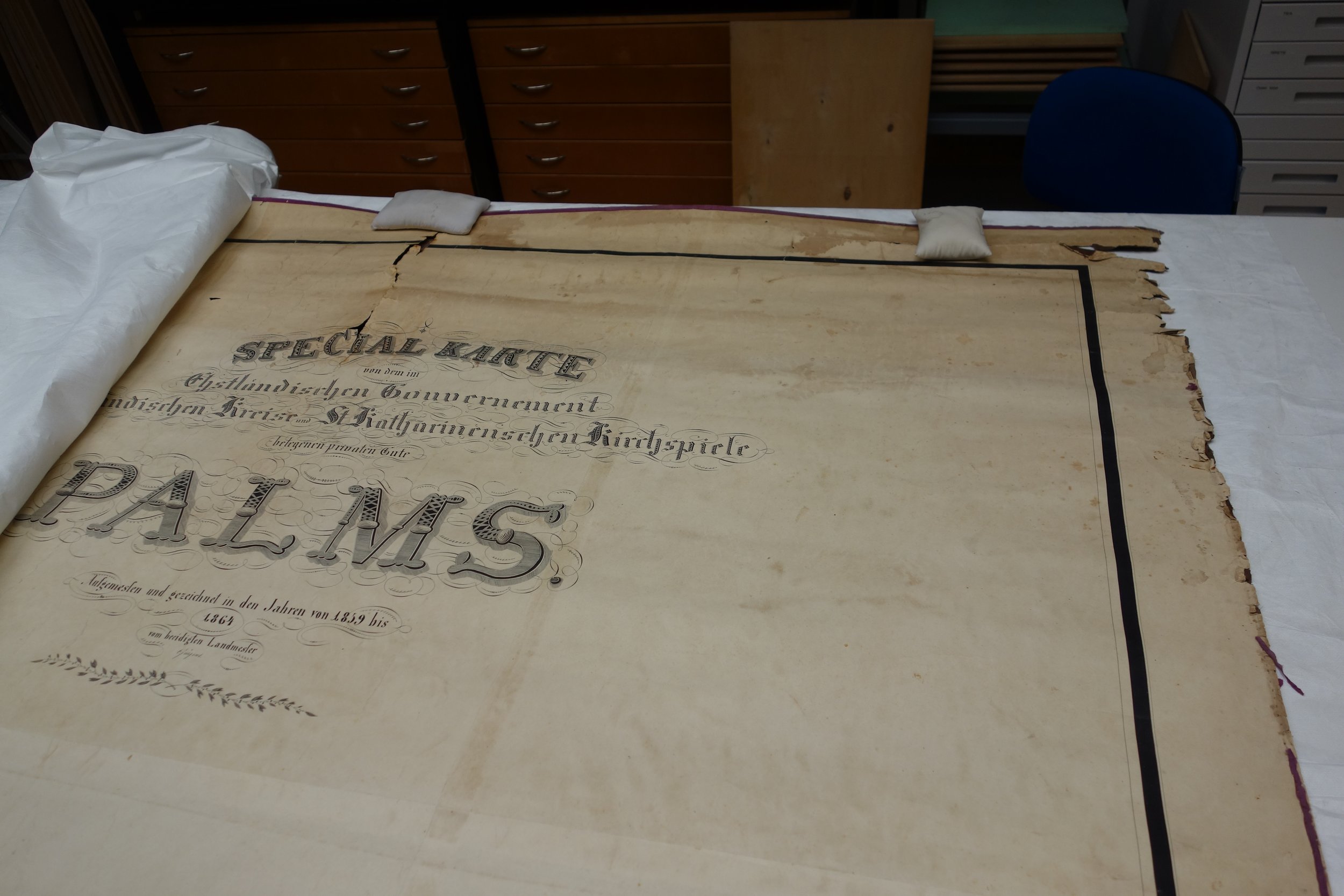

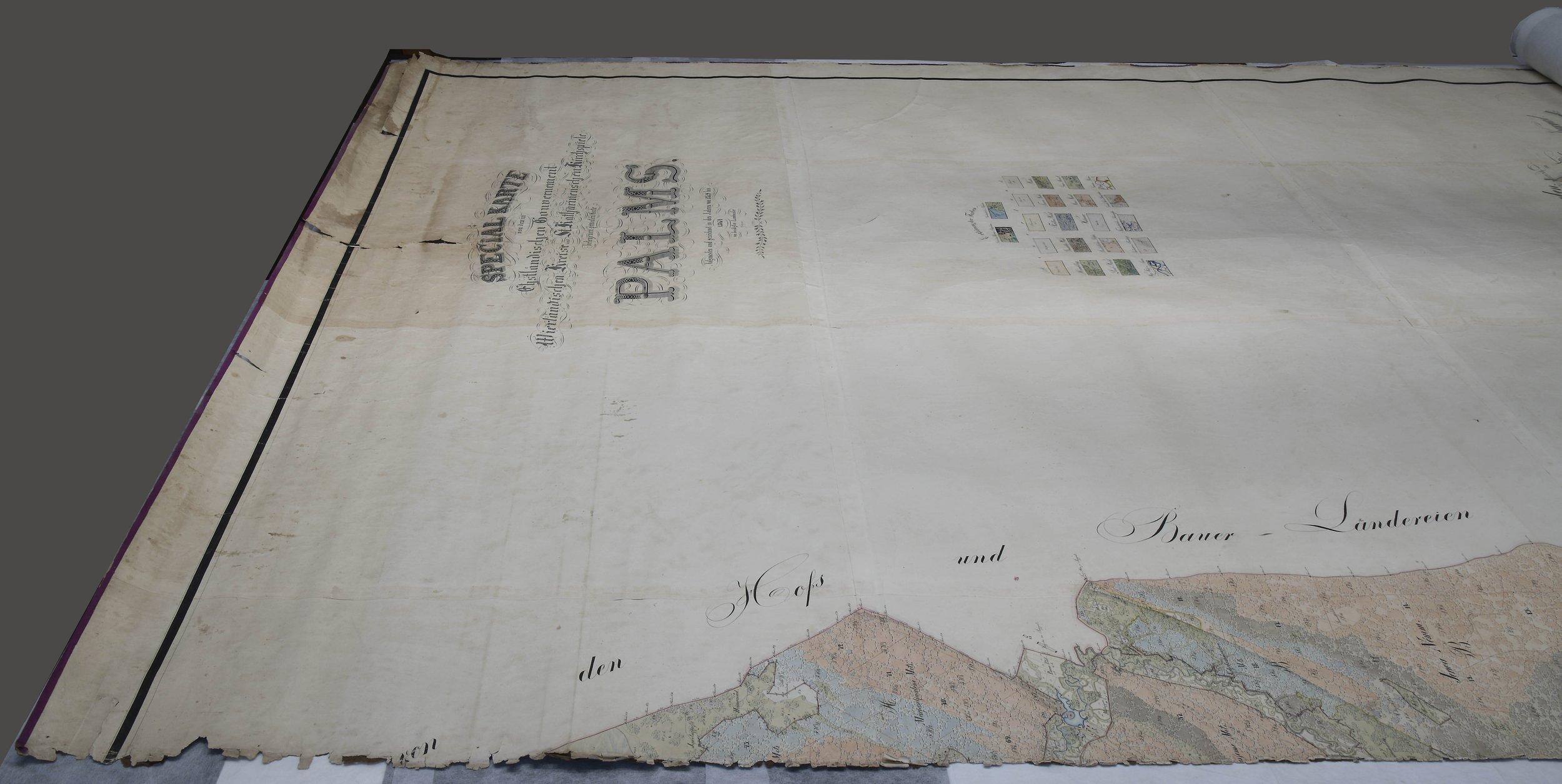

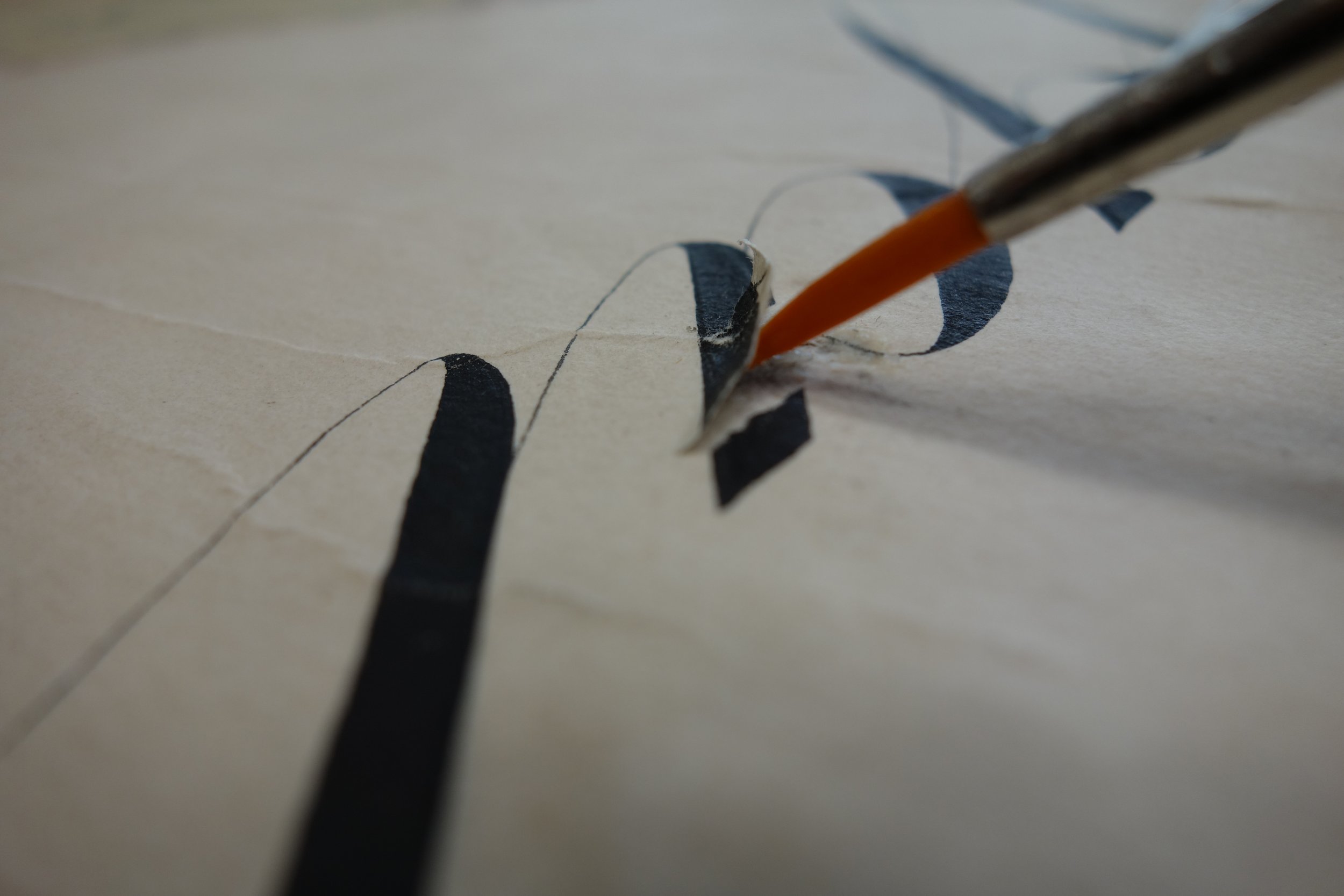

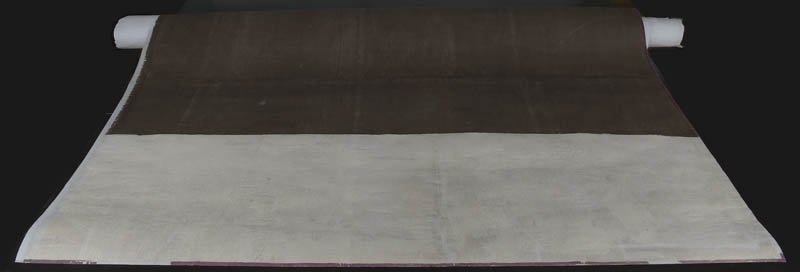

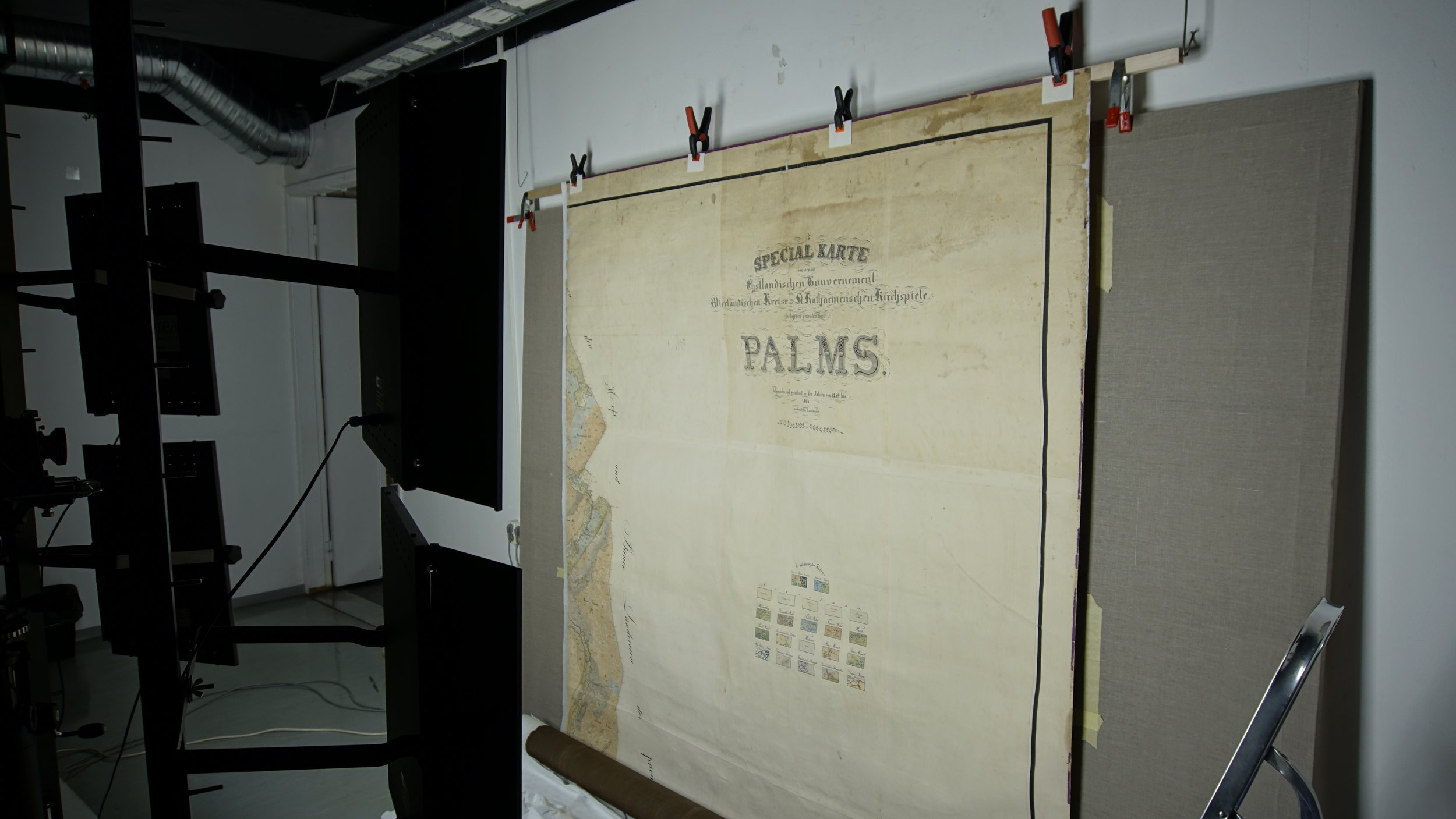

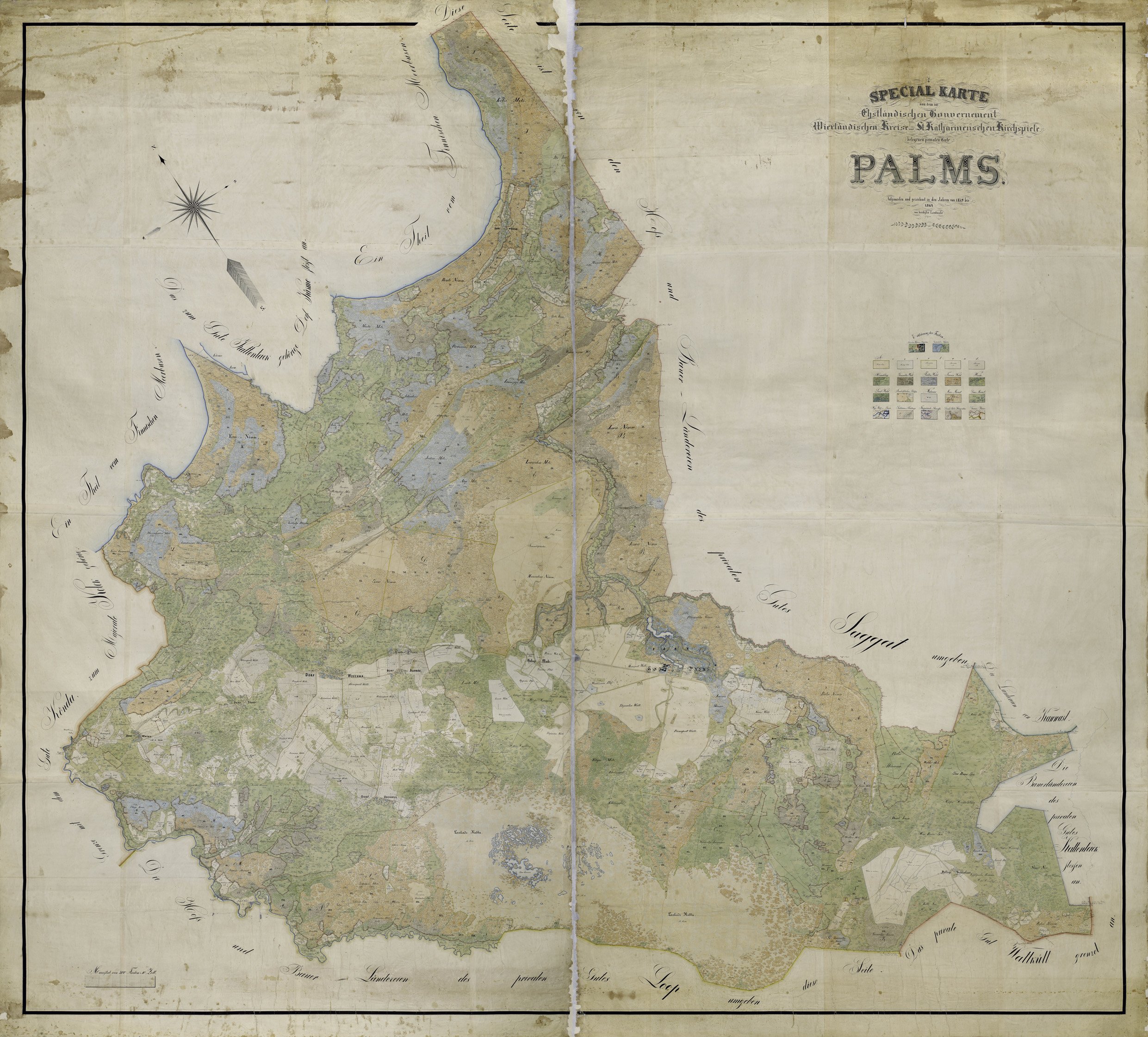

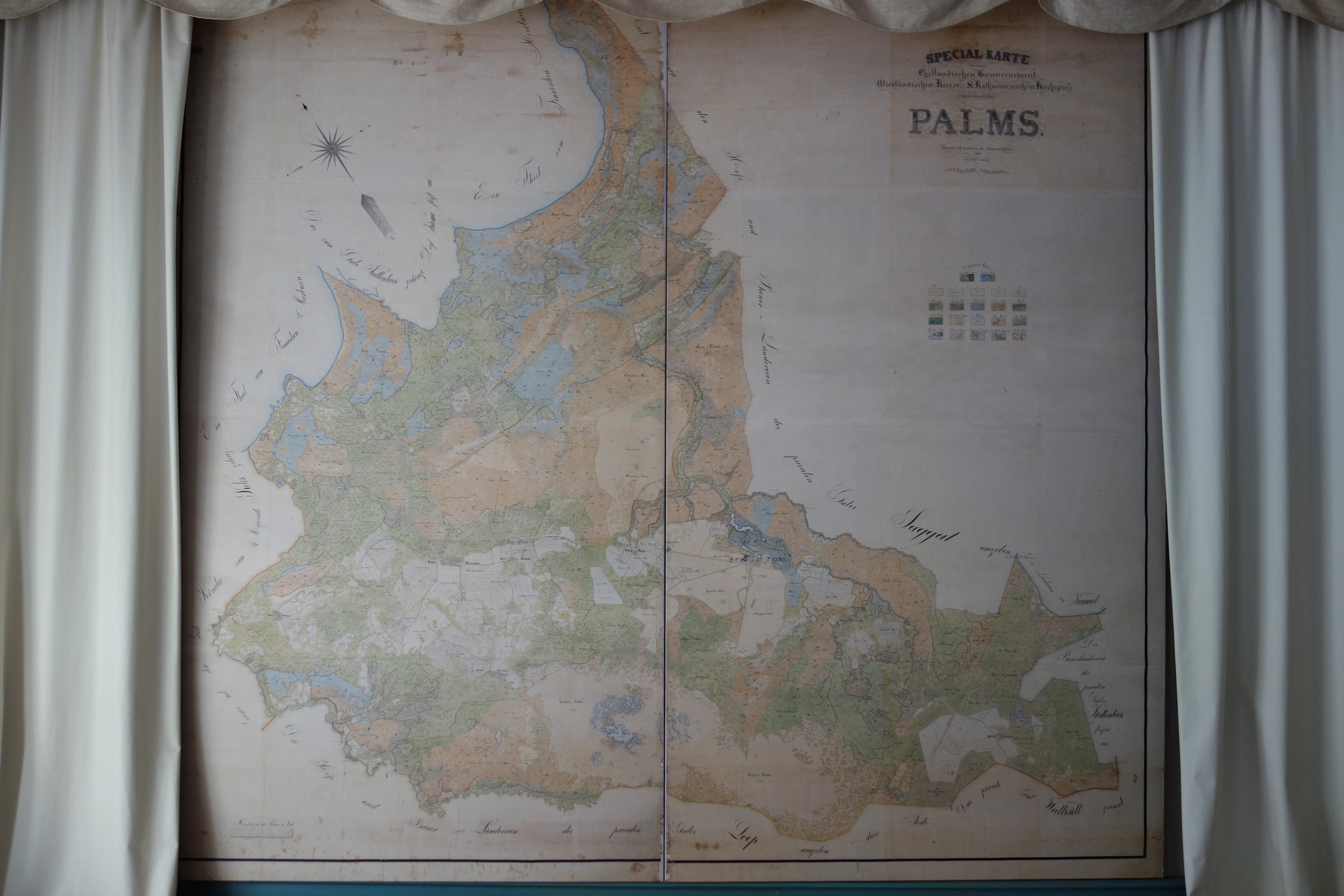

For fifteen years this large map (380x421.2cm) of the manorial lands was hanging on the study wall of the lord of the manor in Palmse, Western Virumaa, Estonia. The author Carl August Jürgens dated his work to 1859-1864. [fig 1] The map is known to be the only one depicting all that time properties of the Palmse Manor Estate in great detail. The map was painted by hand in various inks, India/China inks and watercolours, on an earlier-prepared base. [fig 2], [fig 3] The paper of the base consists of 35 sheets, glued together on edges and then pasted on brown textile lining with wheat-starch paste.(1) All the sheets carry the watermark J. Whatman 1863. [fig 4] A purple silk edging sewn on by hand surrounds the whole. The small perforation holes in the corners of every detail [fig 5] that become visible when looking at the map against the light, were caused by pins, used for marking the images on the paper.

Its large size and abundance of details make the map unique and of great cartographic interest. It offers information on the changes in landscape within the previous centuries and also of even the smallest buildings on the territory at the time the map was compiled.

Christof Nichterlein, a student of cartography at the HSKA (Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences), who wrote his BA paper at the Estonian Life Sciences University in 2016 said the following.

The Pahlens like all Baltic Germans evacuated from Estonia before 1940, but the map was left as a memorial, where it had always been. Its format (size) and content showing the changes in landscape are amazingly rare. It is necessary to make a digitised copy of the map to make detailed studying of it in the web possible. A suitable method for getting a qualified product should be found, as photographing in natural light does not give a satisfactory result.(2)

Nichterlein grades the Palmse map in Kabinettskarten category. This type of maps, usually large and detailed are supposed to cover a whole wall. They are hand-painted and intended to give the owner an opportunity to get a bird’s eye view of the whole property. Their colouring and decorative elements like titles, coats-of arms, vignettes and compass roses make them rather impressive. [fig 6]

Christof Nichterlein’s main aim was to get the digitised map and find the best method to achieve it. He mentions that he was not allowed to use the flash, when he was taking photos for his research and he had to spend hours waiting for suitable conditions of natural light. Even so, several of his frames were not serviceable later on. His observations of the original allowed him to make the conclusion that the Palmse map had indeed been meticulously made.(3)

The large map had been displayed hanging in an open room from 2002 up to 2018, when it was brought for conservation in the Kanut.

The museum wanted the map conserved, since as a document it has a great community value and has been an object of interest for the local people. Conservation was targeted on the possibility to exhibit the map at its original place on the wall of the study.

It should be admitted that the initial assessment of the condition in situ was not exact enough and the first ideas about conservation methods had not taken all the aspects into account. All this became obvious on closer inspection when the map was in the Kanut already.

Description of the conditions and aspects that closer inspection revealed

In the Kanut, after dry-cleaning removed loose dust and dirt on both sides of the map it became possible to assess the essence and condition of different materials, make analyses and decide which conservation processes should be applied.

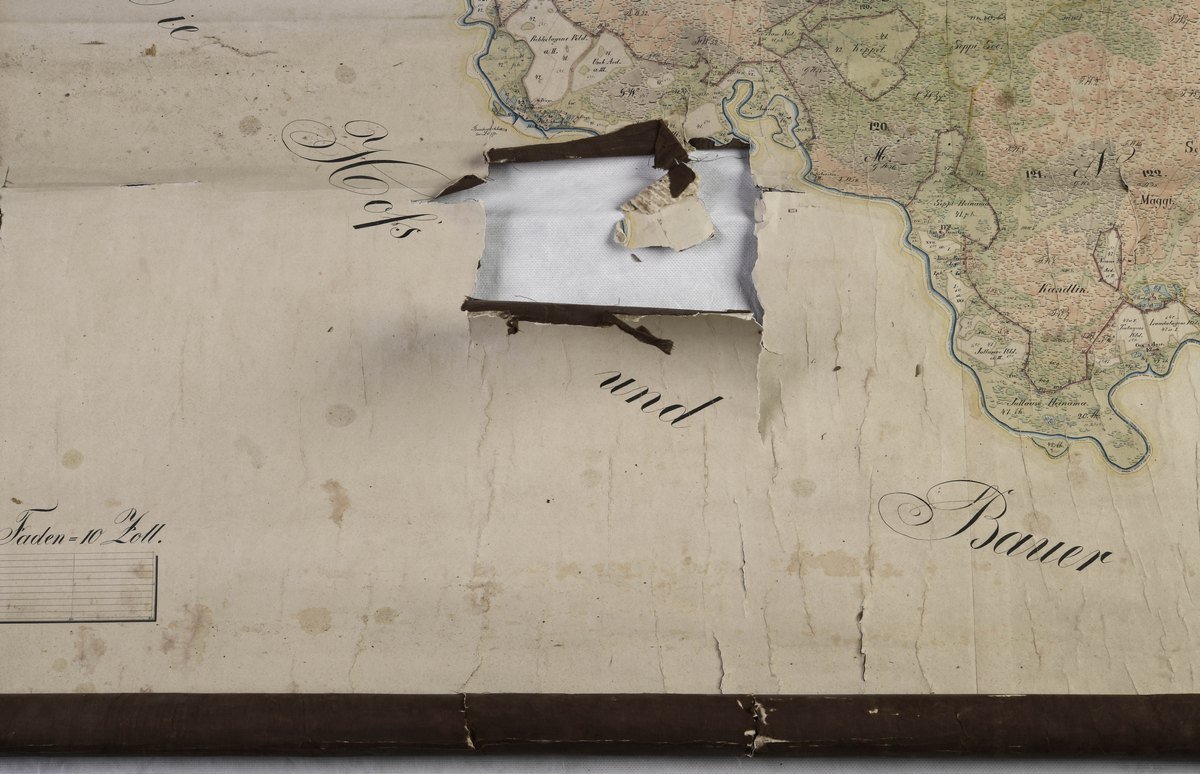

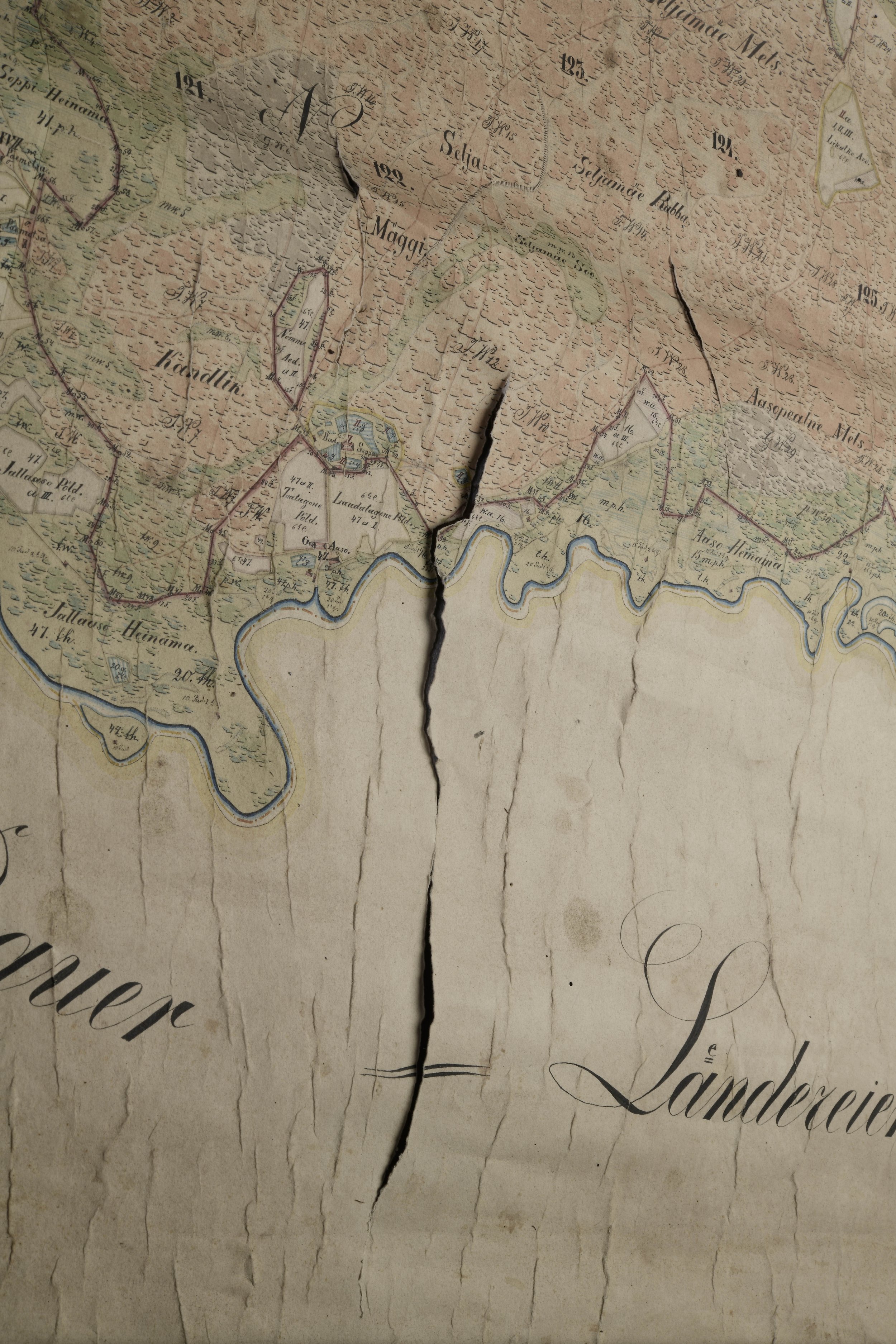

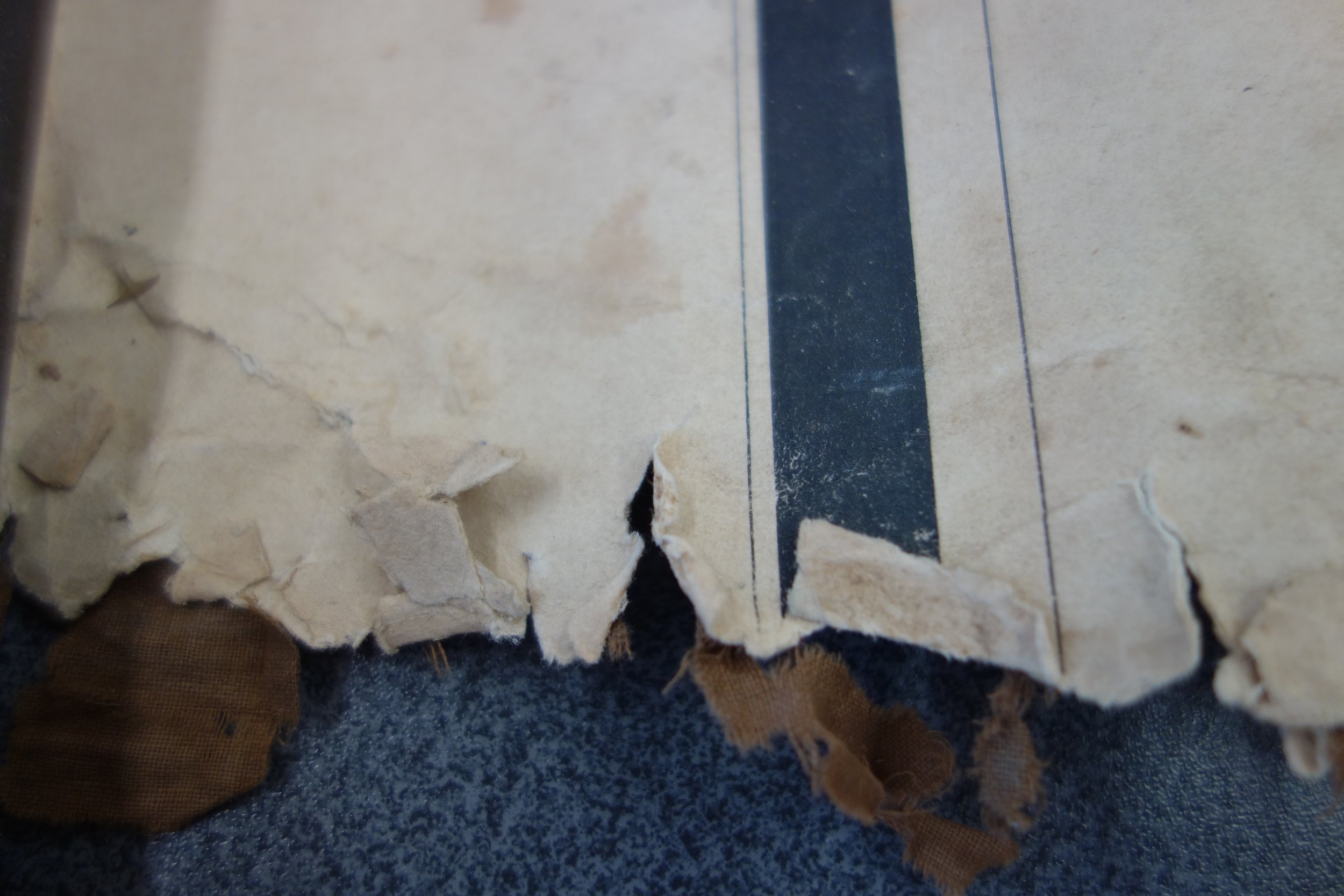

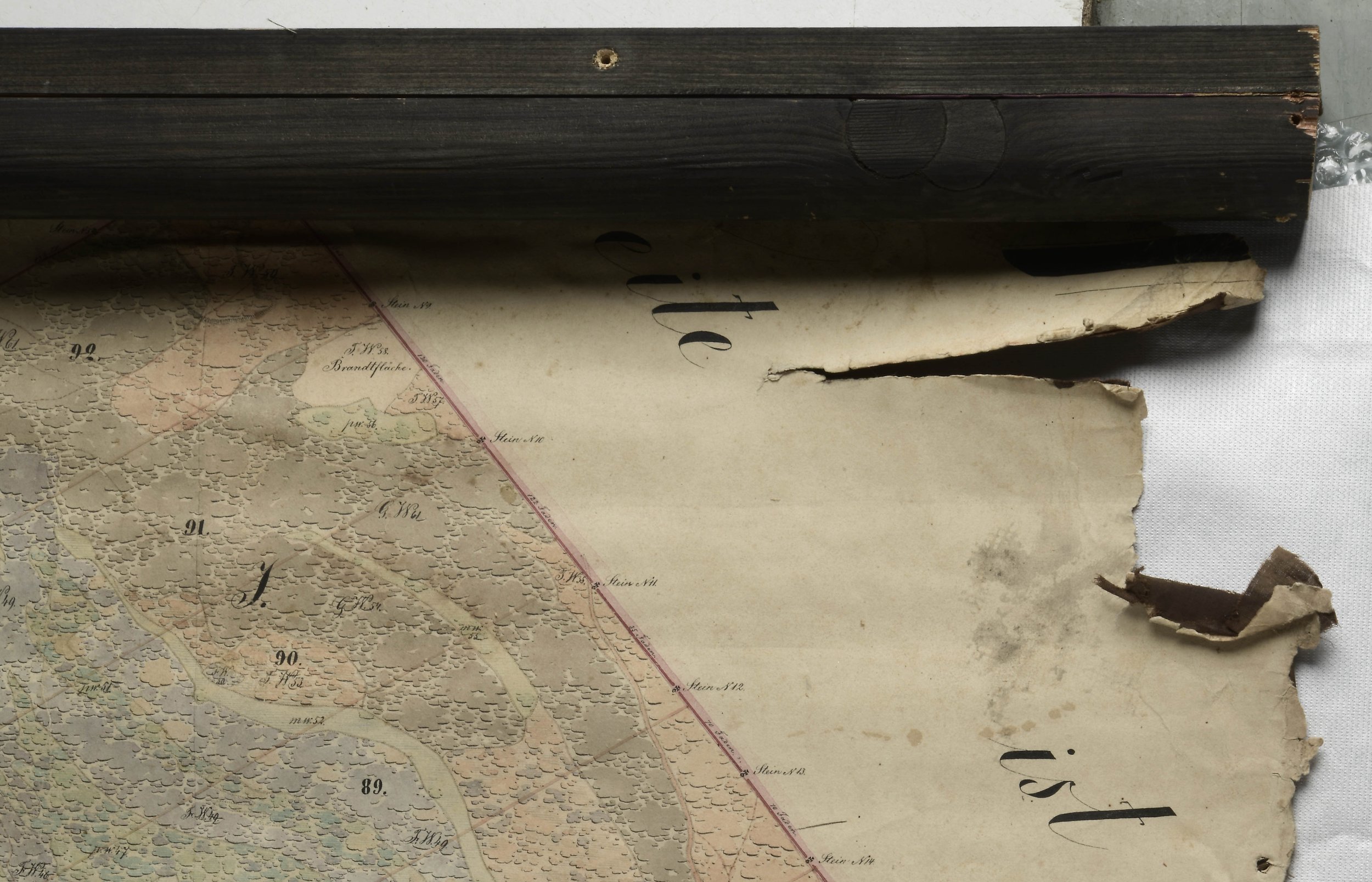

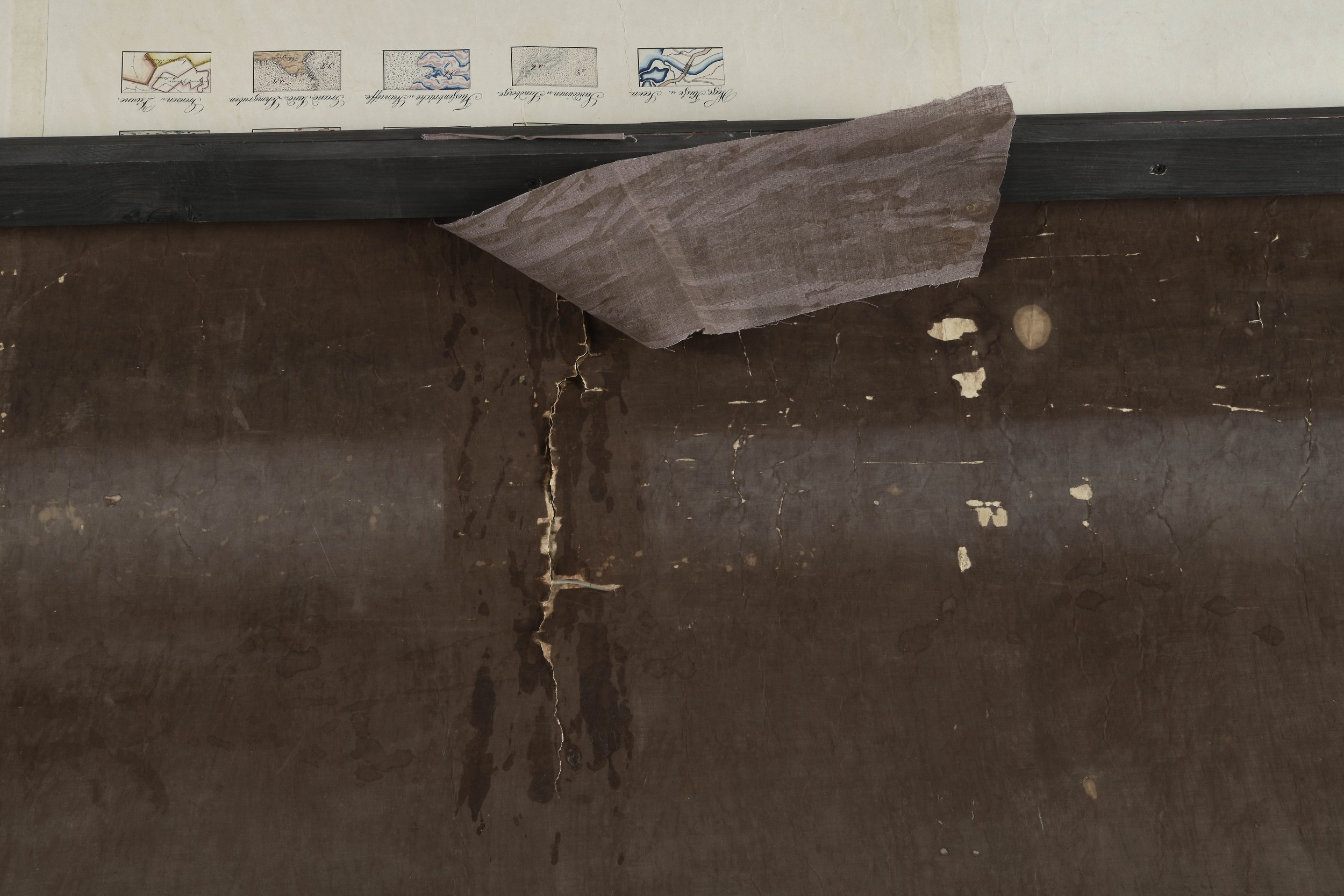

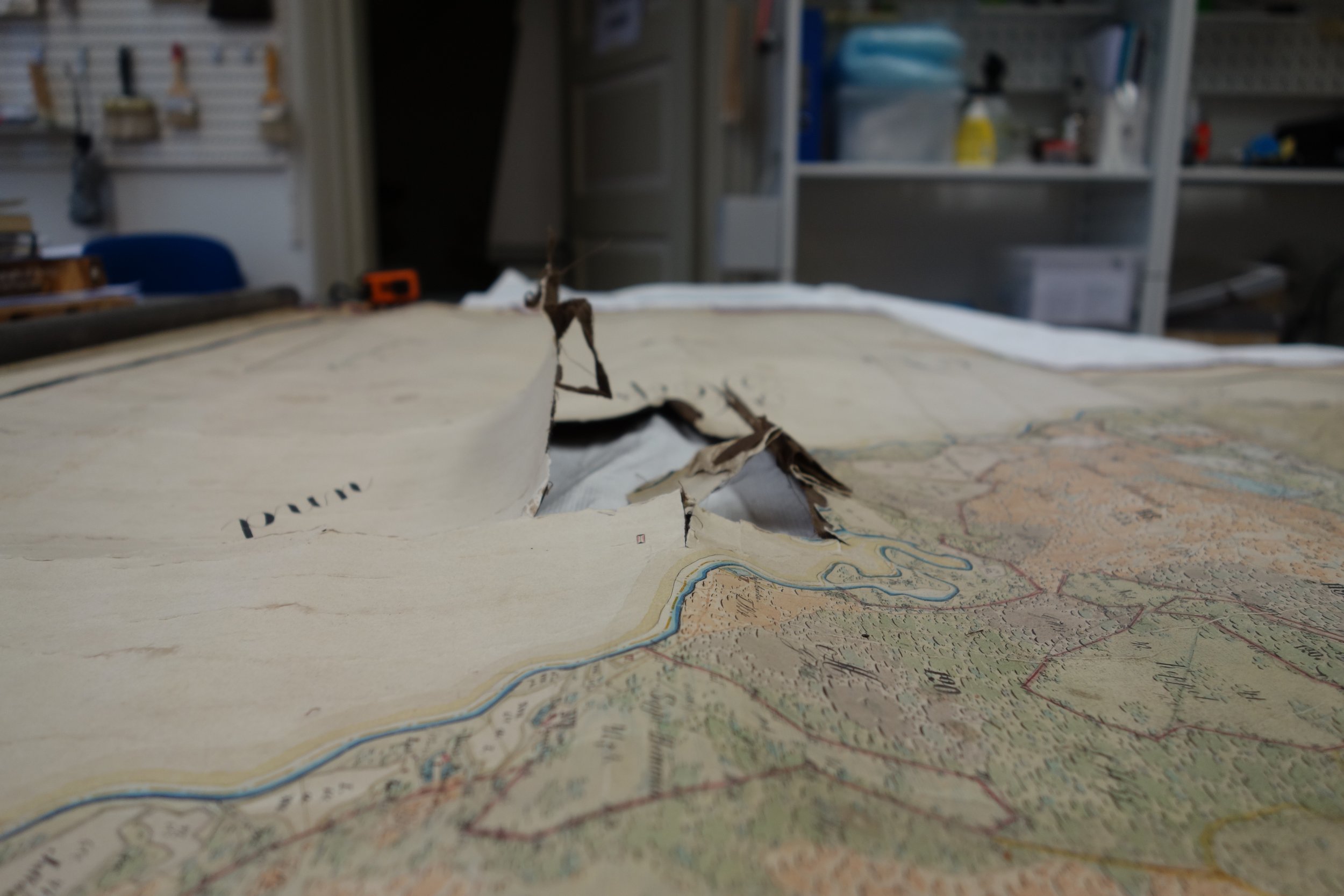

Most of the damage had ensued when the map was being displayed. [fig 7] As the height of the map (380cm) exceeded that of the wall it had been impossible to display it in its natural size. So when it was set up, massive wooden slats had been fixed onto the upper and lower edges that were then rolled around the slats. These rolled-up parts carried a considerably thicker layer of dust inside and outside. The edges were worn and creased having also rips and losses in them. [fig 8] In addition to that there was a break-through hole in the lower part of the map that perforated both the paper and the lining textile. [fig 9] Ruptures occurred all over the map, hinting at the earlier rolled-up storing and later perpetual rolling and unrolling. [fig 10] When the wooden slats were removed it became clear that the upper and lower edge within about 60cm width were in worse condition than the map itself. [fig 11] The creases had turned into longish tears that had some missing fragments in them. [fig 12]

Some tide-lines, a few spots and general yellowing had appeared. The up-most title-bearing sheet on the right had yellowed most of all, although it is difficult to explain why. It is possible that already before painting the map this sheet was the topmost one in the packet and got damaged by light. [fig 13]

At some unknown time the large entity had been halved vertically into two equal parts, 210.5cm and 210.7cm wide. It might have been thought that it was easier to store or even to display the map this way. [fig 14] According to the local legend, the map was found in the attic in two parts, rolled into a case as long as a half of the map. It is also possible the map was halved just to accommodate it in the case – both halves had been rolled up with the depiction inside. It might also have been rolled up as a whole long tube or folded and broken in the centre (the edge of the break has decayed enough to consider this possibility) and that it was just the wear of the break that caused the halving. The line of the halving break, however, is straight enough suggesting voluntary activities and not ripping.

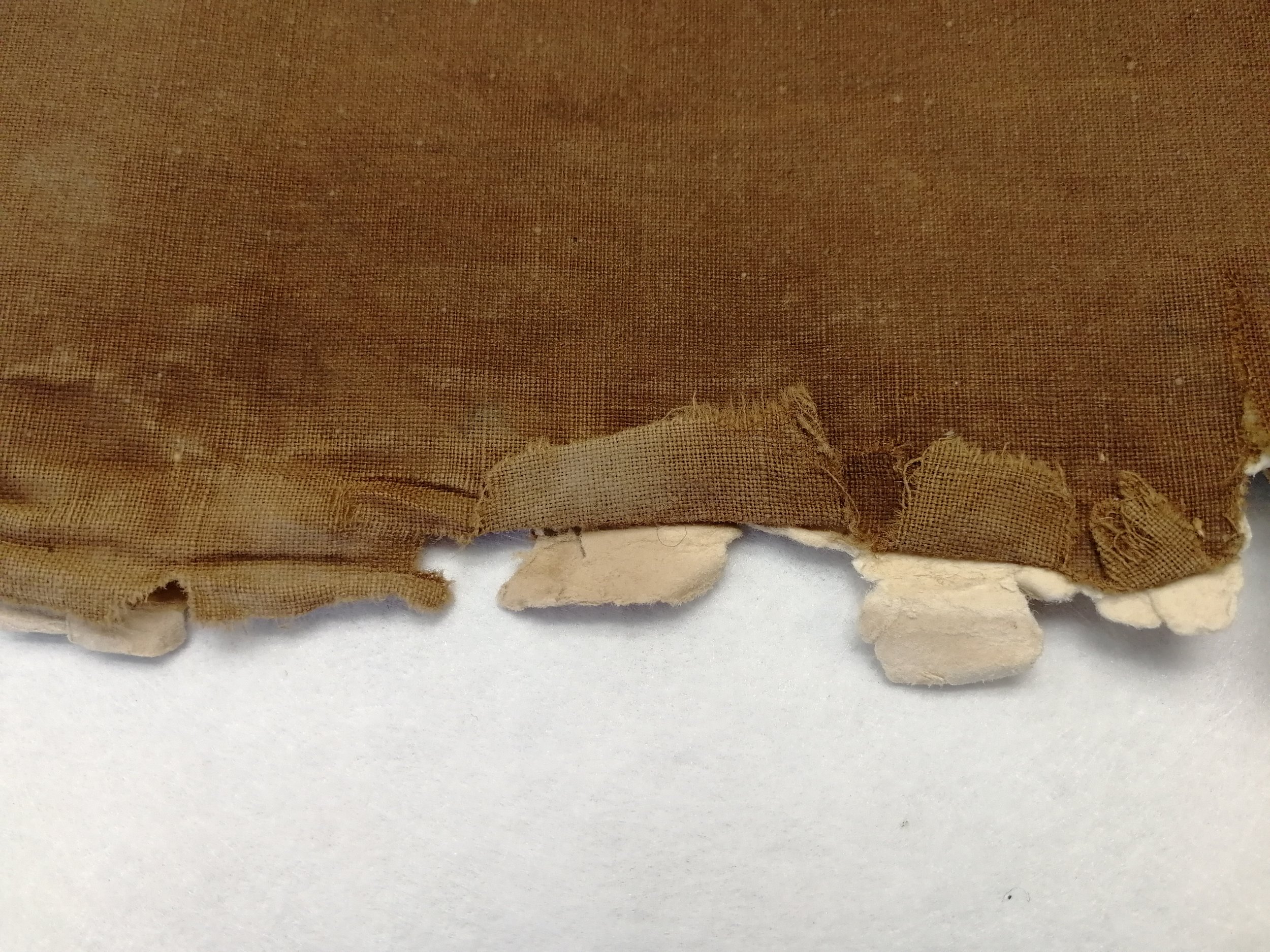

The lining of the map is of thin dark-brown cotton fabric. [fig 15] It was soiled and has traces of wetting – the fabric has darkened and decayed almost to dust and there were tide-lines that were transferred to the paper as well. [fig 16] There are traces of mechanical wear and several losses in the fabric. [fig 17] When observed under enlargement, broken fibres become visible and the fabric seems fragile. [fig 18]

Although rag-paper is known for its durability and persistence, the material of the map in question has turned acidic as proved by tests made both on the averse and reverse sides. The decaying lining had become a danger for further preservation – on the reverse the pH was lower than on the averse. Besides, the starch paste used has darkened and decayed and is causing changes also in the colouring of the paper.

The damaged lining does not support the map hanging on the wall for displaying – both halves have descended due to weight and so stretched unevenly. There are also extensive tears on the borders under the slats. [fig 19] Probably already at the manorial times some of the upper part tears under the slats were repaired with fabric resembling the lining, but obviously bone glue, not starch paste was used. [fig 20]

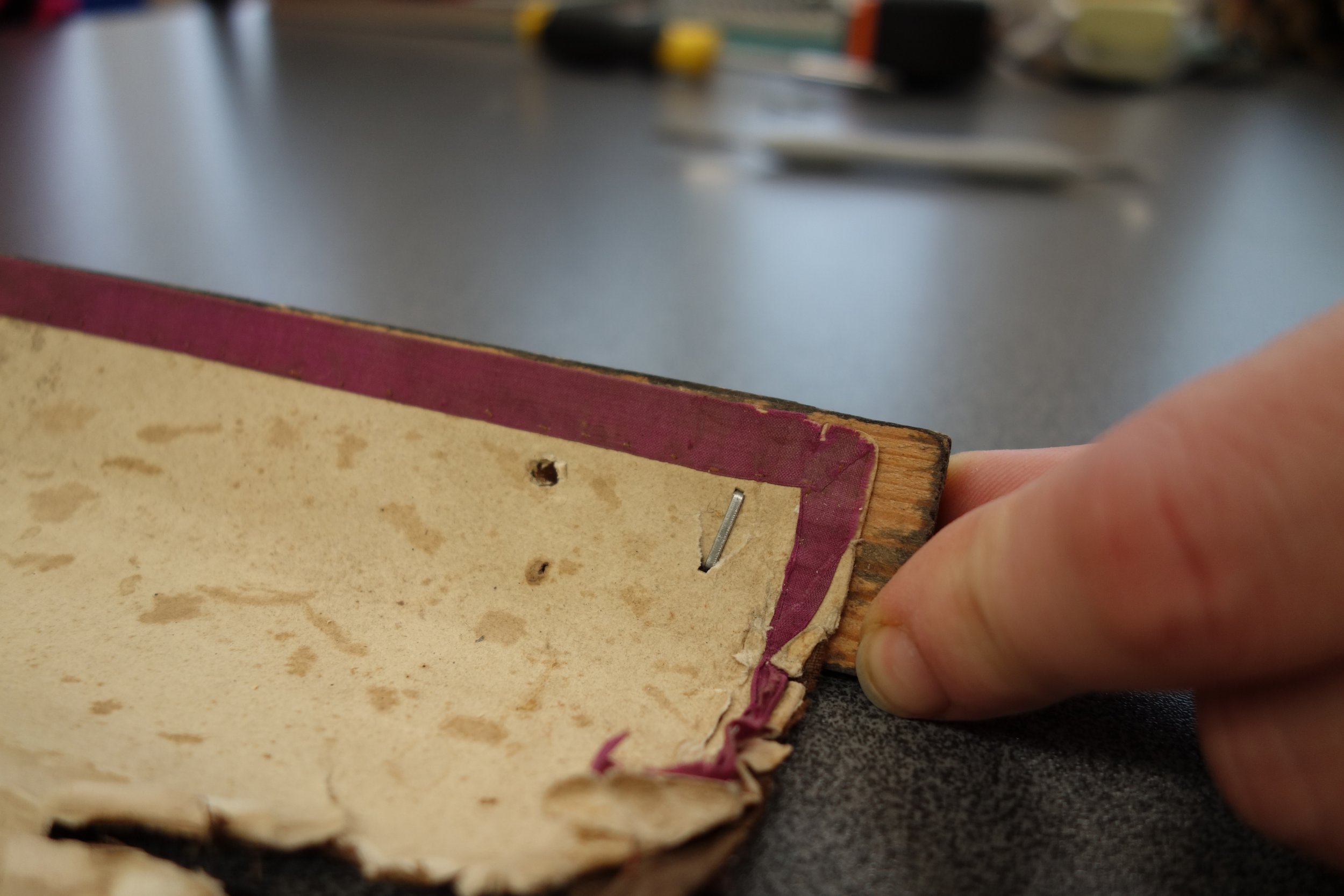

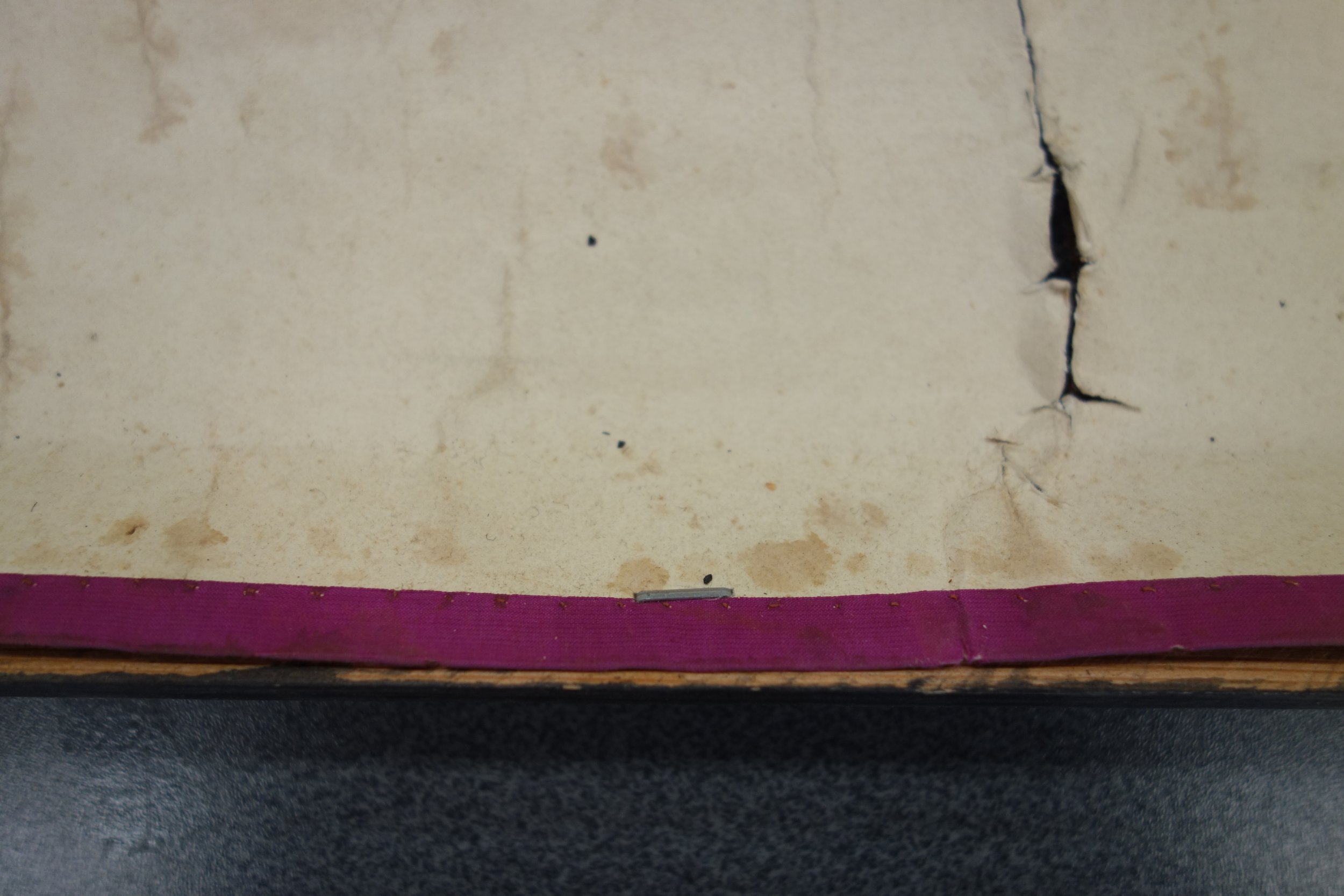

The massive wooden slats fixed on both ends of the map are from the present time. The 21st-century additions are not suitable for further solutions. The back slat that had been fixed with a stapler used in construction and after that the front one with screws both break through the original material. [fig 21], [fig 22], [fig 23], [fig 24] The purple silk edging has preserved better in the area between the slats than on the borders of the map. Obviously nobody thought of hanging the map up initially, as the silk edging is similar in all the four borders and there were no signs of any hanging system. [fig 25] The extensive damage in the upper and lower edge of the map appeared obviously when it was last hung up.

Concept of Long-time Preservation of the Map

The plan of conservation processes was quite a challenge for several reasons. The main problem was the large size of the map. In addition to that the material was water-sensitive: the paper itself as well as all the used inks and watercolours were sensitive to water and alcohol. Another peculiar challenge came from the room, where it was planned to exhibit the map – the study was not high enough. Rolling it partly up would not only have damaged it, but it is not a proper displaying way either.

The conservators discussed the pros and contras of conservation carefully for finding the best solution that would first preserve the map and also satisfy the museum.

1. Conservation of the original map in the way it could be displayed in the manor.

This would have meant extensive conservation and preparation for display. First of all a suitable room that would allow to hang the map up in its full size had to be found. (4)

The best conservation solution is labour consuming and requires proper formation – the old lining should be totally removed and a whole new canvas lining, more persistent than the original one, must be used. This includes detailed joining of the fragmented edges. The original map with the new lining should then be stretched on a solid frame.

Watercolours are no good for long-lasting exhibiting. According to the Blue Wool Standard BS 1006 they belong to the category of the first, i.e. the most photosensitive materials. (5) It means that even in well-checked conditions they could be displayed seldom or better not at all. Paper and museum pieces in general have to be exhibited only in conditions free of dust, light and changes in humidity. In case it is impossible to grant these conditions, the idea of exhibition should be given up. (6) It means that when the map is exhibited in the manor, it should be framed and glazed or placed in a glass display case for protection from straight sunlight and dust.

Unfortunately, the extent of this assignment exceeds the planned one several times – this kind of thorough conservation and proper displaying could not be accommodated within the earlier cost account. Thus the Conservation Centre Kanut advised the museum not to exhibit the original map in present conditions at all.

The conservation had to grant the emergency stabilisation of the original map, so that it would be possible to conserve it totally in the future. It is advisable to keep the original laid out in a shallow case or if it is too large for a case, rolled up on a wide-diameter, solid but soft-surfaced cylinder, however never hung up, as the lining is too weak for that.

An essential part of this solution is making a qualified digitised map or a usable replica that would allow both studying and displaying it. For long-lasting exhibition it should just be a replica that can be hung up on the wall, showing the whole entity.

The museum agreed with the conservators’ suggestion about the minimal conservation and a digitised replica being produced. (7)

2. Conservation of the map for long-lasting preservation in the museum’s depository

The conservation included minimal filling of losses that was vital for preserving the entity. [fig 26] The map was cleaned of surface dust and its tears and missing fragments were locally mended. The fragments and seams of the loose and decayed silk edging were fixed with glue, but the losses were not replaced. The torn edges of the central part were lined with (40g/m2) Japanese paper that reached a bit further than the original’s edge for protection of the fragmented area.

The slabs were not remounted, as they were later-day unsuitable details anyhow. Besides that, the map is not durable enough for hanging up, as the lining does not grant sufficient support for the paper. The surfaces of the map that had been rolled up showed much more damaged and fragile lining than that in the centre. The paper had more physical damage, more tears and losses in the upper and lower borders of the map that needed mending. Considering all that it was decided to remove the old lining in places where it was damaged most. The reverse was dry-cleaned from the old darkened paste. The paper of the original and its losses on the reverse were locally repaired, avoiding moistening as much as possible.

As the total conservation of the map had been postponed into the future unknown and the bigger part of the map was in more-or-less satisfactory condition, it was decided to economise and replace only part of the lining. So most of the map retained its original lining and the most damaged part, where the lining had been removed and not replaced was lined with Japanese paper 20g/m2 (roll-kozo or machine-made paper of mulberry baste).

Japanese paper will give the map sufficient protection until it becomes possible to conserve it entirely and it is also quite suitable for the first lining. The first lining is actually a barrier between the original and the proper lining. It is applied at the conservation of large-scale paper items. This first lining is of neutral material, usually of thinner Japanese paper. It is kept on even when several re-mountings onto textile may follow. This approach is widely applied in Japan, where there are lots of large-scale paper objects, re-mounted on sliding walls or used in hanging rolls. It is attempted to protect the original painting with a thin Japanese paper lining before its formatting already, whereas during the following mountings and conservation even the lining is kept in place whenever possible.

In case of the large-scale map in question an additional thin paper layer in between the original and the lining would have been beneficial, but it has not been an European tradition. When stored the large-scale paper objects that are quite often unrolled and rolled up again the first lining would considerably help to avoid damage. At the conservation of the Palmse map it was decided to have the original stored when rolled onto a wide-diameter tube, enwrapped and in checked conditions. It will not be actively used before the total conservation becomes possible. The digitised replica must suffice till then.

For total conservation the whole lining textile has to be removed. As it has decayed and is rather thin it is not sensible to conserve and remount it. And even when it is decided to still do it, a neutral interlay in between the original and the textile is necessary. In case of large-scale objects the paper lining is often set in 20-30cm high sheets or in horizontal strips that are of the same length as the original. In the conservation of the map in question the first lining strips at the upper and lower edge may stay put during the next conservation and the whole first lining may follow. Only then it can be decided which method of mounting should be chosen – will it be in two parts or will the parts be joined into an entity. The textile lining fabric in the upper and lower edges of the map was so much decayed that it was not kept for preservation.

Description of the conservation processes and materials used. (8)

Dry-cleaning. Loose dust was removed with sponges and a mini-tipped vacuum cleaner. [fig 27] Erasers were used to remove dirt from the most-soiled vacant (with no images) areas. [fig 28] Insect excrements and the rest of similar surface dirt were removed very carefully with a scalpel. [fig 29]

Tests. The result of the lignin test on lining paper was negative (Phloroglucinol reactor). The paper does not contain any lignin and is obviously made of rag-pulp.

Measuring pH results.

Left-hand upper corner, brown spot – pH 3.94; the clean area next to the spot – pH 3.56; reverse upper corner on the left – pH 3.39

Disengaged fragment on the averse – pH 3.64

Disengaged fragment from the paste layer on the reverse – pH 3.46

Removing paste residue and lining from the reverse side of the paper. The old lining was removed mechanically from the most-damaged areas in the upper and lower edges of the map. [fig 30] The paste was removed first with a scalpel and then with cotton swabs, lightly moistened in ca 5% Methyl cellulose (MC) gel. [fig 31], [fig 32]

Repairing tears and filling losses. Smaller rips were mended with 9g/m2 Japanese paper (on the borders under the silk edging) and the tears with 9g/m2 and 20g/m2 paper.(9) If necessary, the paper was used in several layers especially on the reverse side of the map. The losses were filled with suitable rag paper. (10) [fig 33], [fig 34]

Sympatex compress. The places, where the old textile lining had been removed, the reverse side of the paper cleansed of the remnants of paste and necessary repairs made were slightly moistened on Sympatex compress. (11) that made it possible to replace the removed fabric with Japanese paper lining.

Lining. 20g/m2 Japanese paper was pasted with a weak mixture of wheat-starch paste and 1.5% MC glue. The pasted lining paper was lifted onto the reverse side of the pre-moistened original, smoothed down and dabbed carefully with a brush to remove the airbags. Then the newly lined area was left to stabilise for some time underneath thick woollen felt. It was constantly watched and smoothed lightly with fingers through the felt. [fig 35], [fig 36]

Flattening under local weight. Felts were replaced with dry ones and the lined area was left to dry under wooden boards and some local weights placed on them. The next day the felts were exchanged for filter cardboard and back it went under the boards with local weights for a couple of weeks to flatten. The compression was not too hard. The locally moistened areas distend temporarily so it is necessary to provide the processed area with the possibility to retract into its initial size, avoiding unwelcome creases. [fig 37], [fig 38]

Attaching protective lengthening to torn edges. The torn edge in the central part of the map was uneven and damaged, but its decayed fragments had fine images on them. That is why for further protection of the map it was decided to support the tears and fill the losses with strips of 20g/m2 Japanese paper on the edges of the reverse side. The 10cm strips line about 5cm wide damaged space and remain 5cm wider than the image. The strips were covered with another 20g/m2 Japanese paper layer in the way that the edge towards the image followed the damage and filled the losses between the fragments. The edging was attached half-dry in 50cm pieces and the processed area was immediately left flattening under local weights.

Fixing the silk edging. When removing the old lining fabric and cleansing the reverse side of the map from the residue paste some handmade original seams joining the edging and paper had to be cut through. When the rips under the silk edging had been lined with Japanese paper, the preserved fragments of the silk edging were re-pasted onto their initial places. On the reverse side the fragments were pasted either on the old fabric or on the attached Japanese paper lining. The textile was not mended and the old seams were not reconstructed. All the cut seams were left at their initial place and loose threads were fixed with paste. The processed places were flattened immediately under local weights.

Finishing. The edges of the patches were pared smooth and overlapping parts were cut off. Where necessary the edges were smoothed half-dry with a spatula and paste. The hanging pegs were not replaced and nothing new was added.

Making the case and packing the map for storage. A solid, large-diameter tube with a soft surface was made for storing the map in the depository. The base made of hard cardboard was covered with several layers of foam polyethylene.(12) that in its turn was clad with two layers of Tyvek. The two halves of the map were separated with tissue leaves, wrapped around the tube and enveloped within Tyvek. [fig 39], [fig 40], [fig 41], [fig 42]

Making the digital copy and displaying it in the Palmse Manor

The conserved original was digitised at the Kanut in several parts and the image was mounted by Kanut’s partner enterprise Artproof OÜ. [fig 43], [fig 44] Processing the digital image was considerably influenced by misfortune of the original paper stretching at the halving line. The damaged area remained visible as a contrasting streak and the original images in the area could not be joined for hundred percent in the same way they had been before the halving. Due to a tear extensive paper losses occurred on the borders of the map and this made it impossible to mount the digital image as an entity without the white streak in the centre.

As the original had been hanging on the wall in two parts and the measurements of the planned copy were big, it was decided to form the copy in two separate panels that would be mounted on the wall next to each other. [fig 45], [fig 46] Considering the measurements of the wall the copy was made in size 280x310cm. Subscription of the digital copy started with negotiations in the partner enterprise Artproof OÜ, the specialist of which helped to choose the material for the base, estimate the quality of the image and arrange several printing tests to assess the colours that would be the closest possible to the original. The digital copy made at the Kanut was processed ready for printing and there it was printed on canvas. The halves were framed in aluminium. This way formatted panels, displayed next to each other made the damaged streak less visible than it would have been when made into one entity. (13)

And then, finally, as it turned out at the Palmse Manor, it was still impossible to get the panels of the copy up the winding stairs and they could not be taken in even through the window!

When the winding staircase had been measured earlier, somehow a small slat on the wall was not noticed. But this small slat was enough not to let the panels pass. The conservators like to think of themselves as invincible and thus one of the long slats of the base had to be temporarily removed. Just risking one’s mental health and in the sweat of the brow the wobbling panels had to be dragged through the stairwell and assembled again on the upper floor, where they were put up on the wall. This was achieved by the conservators of the Kanut together with the supportive staff of the manor. All is well that ends well. [fig 47]

Summing up

Conservators of the Kanut insisted the museum not to display the original map in present circumstances and recommended only a preventive conservation for stabilising its condition until possible future conservation. They did not exclude the possibility of total conservation in the future. Making the digital and usable copy of the original map was an essential part of the whole process.

The museum agreed with the proposed solution and the recommendation of displaying a slightly decreased copy of the map in the squire’s study. Hereby we would like to thank Pilvi Põldmaa, the chief curator of the SA Virumaa Muuseumid, who understood our reasoning and offered valuable help to explain everything to the museum staff.

The map was conserved with the aim to digitise it and to store it in the depository. The digitised image was used to make a decreased copy that would match the size of the study wall. It was printed on canvas and formatted in two parts. This solution was selected owing to the fact that the map had been displayed on the wall in two halves hanging next to each other throughout the last fifteen years. It has not been discovered who halved the map and why it was done. The original was not assembled into one entity during the conservation process either. It was decided to store it in separate halves until the decision on the possible following conservation is made.

Conservation: Paper conservators of the Kanut: Maris Allik, Tea Shumanov, Grete Ots, Kaisa Milsaar and curator of the SA Virumaa Muuseumid Eve Einmann.

Digitising: Martin Sermat, Jaanus Heinla, Jaak Rand

Copy made and formatted for exhibition: Artproof OÜ, Tallinn

The report on Palmse map, its conservation storing and displaying for the international conference Alexander von der Pahlen 200 was made by Maris Allik and presented by paper conservator Grete Ots and digitiser Jaan Rand. The SA Virumaa Muuseumid, Palmse Manor and SA Eesti Vabaõhumuuseum (the Estonian Open Air Museum) were the organisers and managers of the conference in 2020.

REFERENCES:

References and Comments

1. SEM-EDS analysis – paper, lining textile, adhesives. TÜ Katsekoda, report on the analyses, 2019

2. Christof Nichterlein, The Estate Map of Palmse Manor. A Comparison of Past and Today and the Way to an Open Source WMS, 2015/2016, Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Information Management and Media –http://mapanddesignspecialist.azurewebsites.net/

3. Ibid. The work written in 2015 describes the visible part of the map that was displayed on the wall of the Palmse Manor at that time in a partly rolled up way (ch.2.2. b, p7). In chapter 3.1.d p 30 we find the description of the map, the legend on pp22-26.

4. The room on the first floor where the map had been displayed might not have been the squire’s study initially. The rooms on the ground floor are higher and would suit better for exhibiting the map. However, there are no signs left about the initial display and this leaves the question about the use of the map unanswered.

5. http://www.ra.ee/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/eksponeerimine.pdf , p27

6. Konsa, Kurmo. Artefaktide säilitamine. (Keeping artefacts) Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2007, p 141

7. Timeline of the conservation: in February 2017 the SA Virumaa Muuseumid started the negotiations with the Conservation Centre Kanut on a possible conservation of the map, in the course of which primary calculations were made (Heige Peets). In October, 2018 specialists of the Kanut (Heige Peets, Sille Siidirätsep, Martin Sermat and Grete Ots visited the manor to assess the condition of the map. The map was taken off the wall, wrapped on a temporary tube for transporting and taken to the Kanut. On 12 December 2018 preparations (i.e. photographing, investigations of the condition and compiling the conservation plan) were launched. On 7 January 2019 practical work, supervised by Maris Allik started at the Kanut. Negotiations with the museum about changes in the initial conservation plan continued from January to March 2019. We advised not to exhibit the original map and make a digitised copy instead. The conservation was completed on 23 May 2019. In May and June 2019 the map was digitised and the image for the copy was prepared. The Artproof OÜ, Tallinn printed out the digitised copy. The conserved map was transported from Tallinn to the depository of the SA Virumaa Muuseumid on 20 July 2019 and the copy was mounted in the manor house of Palmse.

8. Documentation of the conservation process. 18P060 Conservation Centre Kanut Digital-archive (Picture bank)

9. Paper Nao, https://www.stroll-tips.com/en/paper-nao / 4-37-28 Hakusan, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo TEL 03-3944-4470 – https://www.papernao.com/

10. Maksing OÜ, conservation materials import. Paper-shop Zelluloos, NarvaRd.38, Tallinn – https://www.zelluloos.eu/

11. Sympatex is synthetic felt coated with a membrane that lets moisture through only in one direction and only as vapour, not liquid. This gives an opportunity to moisten sensitive materials without touching liquids, only on the principle of a humidification chamber. Preservation Equipment Ltd. – https://www.preservationequipment.com/)

12. Foam Polyethylene (PET), Emballage Technologies Tallinn OÜ (Estonia, importer sales,tallinn@team-et.ee.) Excerpt of the product’s listing: black soft plastic. Foam Polyethylene is protective material that softens the influence of jolts and is easily processed – it can be cut and swaged. This material is moisture proof, light and elastic, thus good for packing.

13. Rand, Jaak. Konserveeritud kaardi digitaalne printimine Palmse mõisakaardi repro näitel (Digital printing of a conserved map based on the Palmse estate map), Renovatum Anno 2019/2020. https://renovatum.ee/autor/konserveeritud-kaardi-digitaalne-printimine-p...