JAPANESE PAPER USED FOR VARIOUS MATERIALS IN CONSERVATION

Autor: Jolana Laidma

Number: Anno 2019/2020

Category: Conservation

Conservation

Most of the conservators, who have worked with paper and binding are aware that one of the best devices to repair them is Japanese paper or veil paper. It may have different thickness due to its fibres of different length and strength and so it enables to make repairs that are almost invisible but still durable.

My own experience has confirmed that Japanese paper is an excellent means for conserving leather, wood, bone and even chitin. Using wheat-starch paste or PVA glue small loose details can be fixed with Japanese paper. It can also be used for filling smaller losses and model missing details, if necessary. Later on the repairs can be toned and made invisible, so that it is possible to view the object as a visual entity (1) .

The present article deals with three noteworthy conservation assignments in which cases Japanese paper was handy for restoring a wooden sarcophagus for a cat’s mummy, a stuffed crocodile and the broken chitin of a pink spiny lobster.

Egyptian sarcophagus of a cat’s mummy

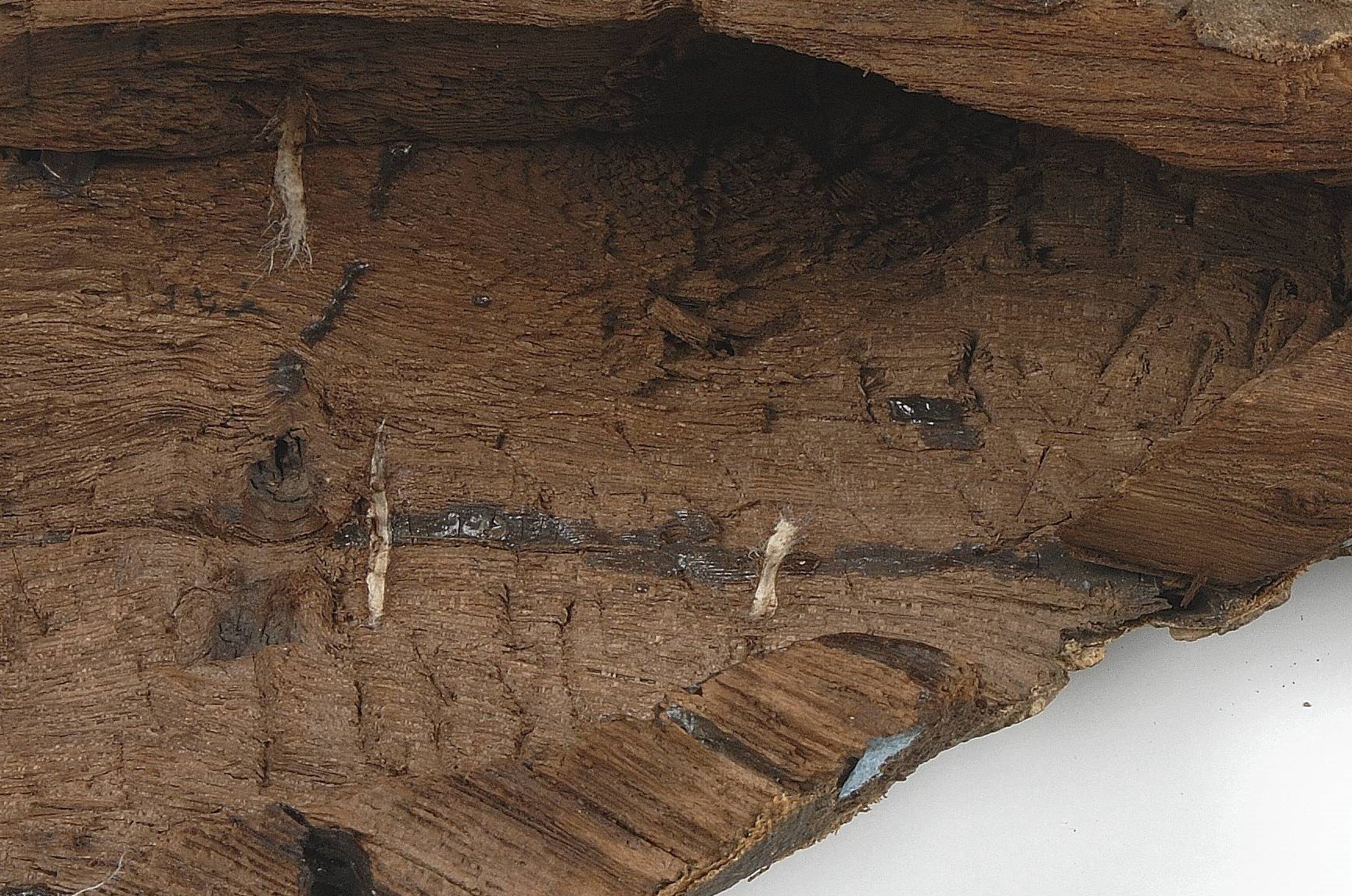

The framework of the almost 2000-year-old sarcophagus, modelled like a cat sitting on a base was made of porous tropical wood (2,3). [fig 1], [fig 2], [fig 3]. A bigger part of the shell was kept together with three-fold linen fabric soaked in glue [fig 4]. The sarcophagus had broken into several parts, so the figure had no ears, nose, tail or paws any longer. Most of the polychrome coating had also perished [fig 5].

Earlier the figure had undergone various repairs. The hole on the scruff had been filled with blue cardboard that was covered with a piece of the original linen fabric [fig 6]. Somebody had attempted to re-stick wooden details with cabinet-maker’s glue, but porous wood is too fragile to stand the stress caused by hard glue drying [fig 7]. The process had brought along new breaks and made removing of the hardened glue from the fragile surface almost a mission impossible.

The aim of the job was to strengthen the framework of the sarcophagus and give it the finished look again. The framework consisted of several loose and broken wooden details that were fastened by means of dowels. Already the initial observation showed that these details could not be fastened in the common edge-to-edge method. The means of joining the details in the way that would allow the wood respond to the environmental changes but still remain stabile was to be invented yet. The moving cracks had to be fastened without glue. Joining wooden details with the help of wooden pins or cogs is a well-used method in conservation practices. Following that, it was decided to bridge the cracks with Japanese paper, a far more suitable material in case of fragile wood [fig 8]. Wheat-starch paste being more agreeable with Japanese paper was used for gluing.

Small grooves were cut across the crack with a scalpel and they were filled with Japanese paper strips that had been coated with paste. This fastening proved to be strong enough [fig 9]. As no glue was inserted straight into the cracks, the wood is allowed to react to environmental changes due to the existing fissures and would not crack anew. This way no new stress appears in the material and the old wooden shape remains stabile [fig 10].

The broken parts of the sarcophagus could not be fixed side to side due to the losses in the wood. A papier-mãché shape was prepared for compensating the missing wooden details [fig 11]. The broken parts of the paws were substituted with darkened bamboo pins that were supported on a small wooden block. The bamboo pins were fixed with paste and Japanese paper [fig 12]. The object that had initially seemed to be rather hopeless in a conservator’s view became a stabile, visually quite enjoyable thing [fig 13],[fig 14].

Stuffed crocodile4.

When the crocodile was stuffed, its skin had been removed in one piece [fig 15]. A long cut runs from its neck up to the tip of its tail underneath. It had been sewn together with leech-rope (top-rope) [fig 16]. The stuffed crocodile had been filled with wood-shavings and the skin with its robust scales had been lacquered. The soles of its feet have small holes in them, obviously caused by nails that once fixed the stuffed reptile on the base. The base itself has not preserved.

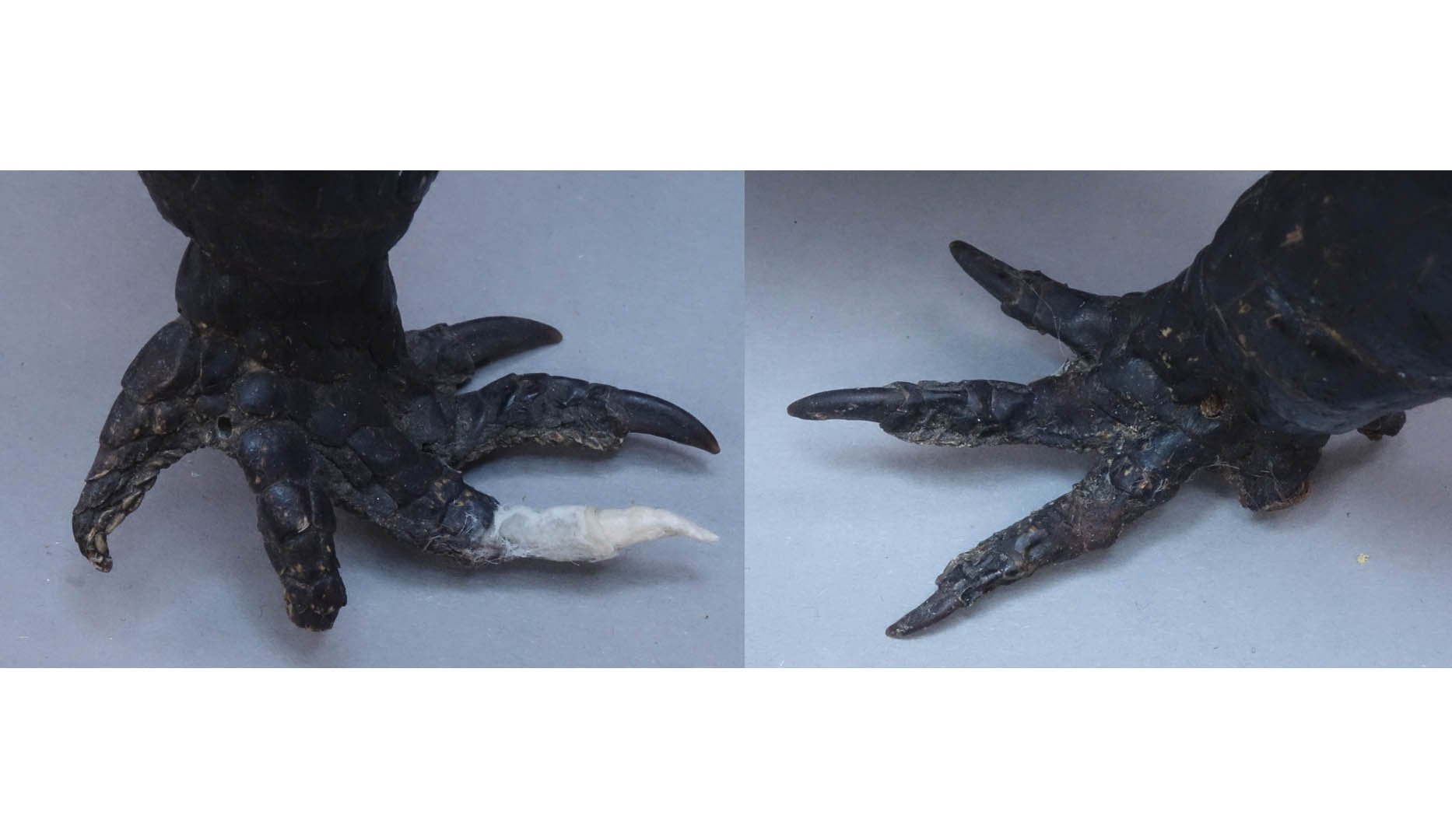

The stuffed crocodile had fallen down and broken [fig 17]. The skin of the front paws had tears in it and the tip of the tail had broken into two parts that were hanging from the rope [fig 18]. Some toes were also broken [fig 19]. Japanese paper is especially good in the cases that do not allow supporting the break from the back. The paper patch on the upper side becomes semitransparent when drying up and will be almost invisible, showing the relief and original look of the surface. The good adherence of Japanese paper with other materials also plays a significant role. When the glue has dried up the paper becomes hard and would be a good support for the surface. As the skin of the stuffed crocodile had been lacquered, it was decided to use synthetic glue PVA that adheres better with a lacquered surface that starch-paste.

The broken limb got a bamboo pin inside and the foot was coated with PVA [fig 20],[fig 21], [fig 22]. The crack in the tail was fixed with a wooden stick and the hole filled with Japanese paper [fig 23]. The joints of the breaks in all the described details were covered with 20g/m2 Japanese paper and toned invisible [fig 24].

The toes were modelled of veil paper, layer by layer, on a strip of thicker Japanese paper (40g/m2) [fig 25]. Before a new layer was added, the previous one had to become dry [fig 26]. A blend of PVA and wheat-starch paste was used for modelling. The toes fastened straight onto the object became strong and stabile and did not need any additional backing [fig 27]. Toning was completed with acrylic paints that become matt when drying. As the rest of the object is glossy, repairs are visible [fig 28]. When displayed and stored the tips of the crocodile’s toes should not touch the surface of the base straight, as the weight of the whole would be too much [fig 29]. That is why small balls of Japanese paper were made to insert them under the soles and support the object [fig 30].

Chitin carapace of a lobster (5).

Conservation of the chitin carapace of a lobster was a challenge indeed.

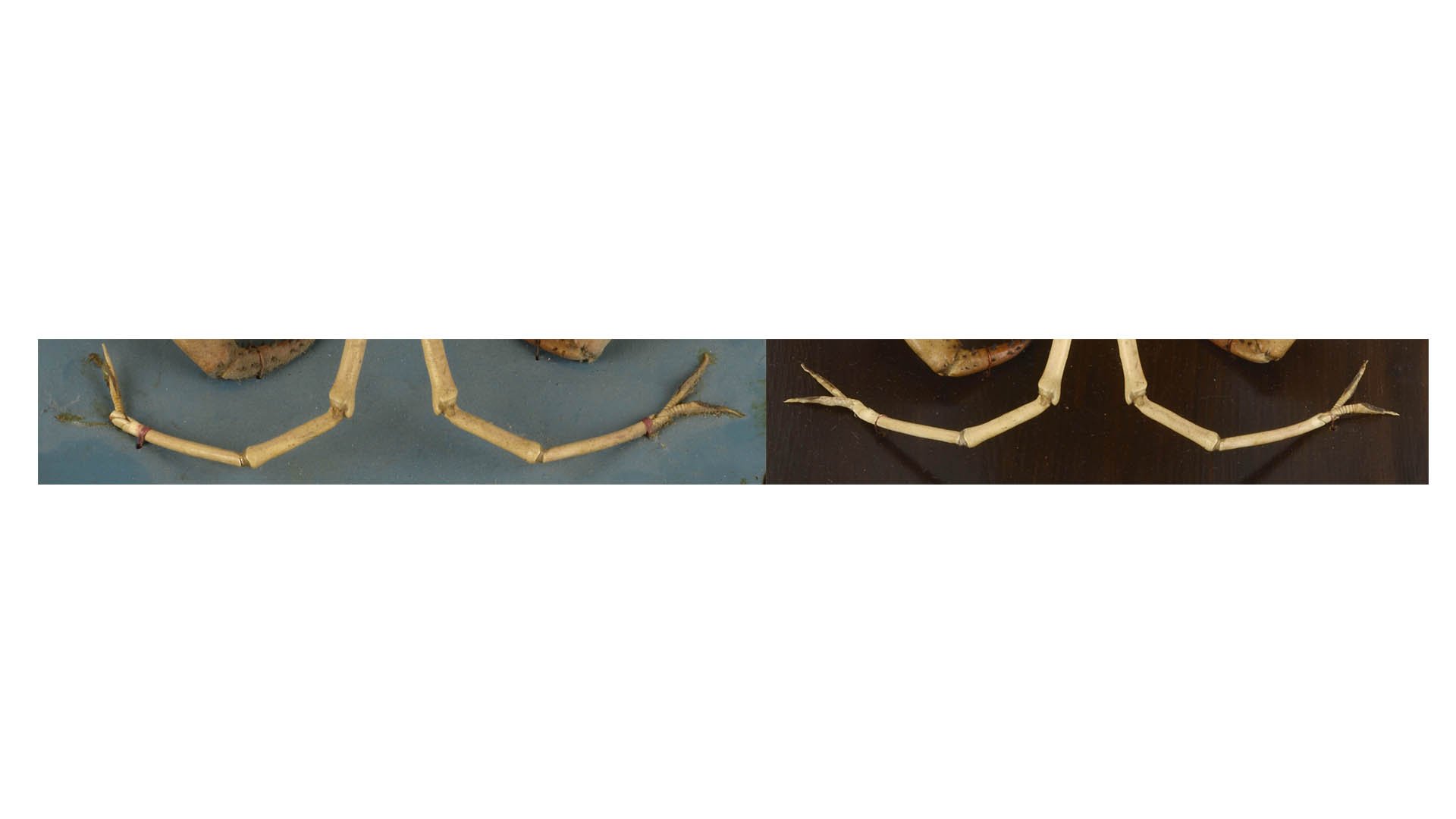

The lobster had been set on a piece of ruffle-board painted blue, whereas its body was surrounded with thin wires that fastened every limb onto the base. Some jolts, however, had caused broken limbs and they were there only thanks to the wire within the pieces [fig 31]. Some smaller details were missing, such as the tips of the right-side whiskers, the tips of the keratin scales on the carapace and the edge of the tail fin [fig 32], [fig 33], [fig 34],[fig 35]. The owner of the stuffed crustacean wished it spruced up and a new, better-coloured slab made, so to say the object should be made displayable.

First of all the crustacean was dismounted and every broken piece was set in its proper place according to the anatomy of a lobster.

For repairing the chitin carapace Japanese paper and wheat-starch paste were the best means. The paper had been toned before (6). and thanks to that the patches were of the right colour and agreed with the surface of the chitin carapace from the beginning [fig 36], [fig 37],[fig 38],[fig 39], [fig 40],[fig 41],[fig 42].

The new base was made of wood and stained brown like the owner wished. The crustacean was placed on the slab and fixed with new thin copper wire in the same way, as it had been fastened before. For fixing, holes were bored into the base under every limb. This helped to fasten the fragile details onto the slab [fig 43], [fig 44]. The new base was covered with green broadcloth on the reverse side and provided with two hanging loops [fig 45], [fig 46].

Summary

Objects of several mixed materials are being brought onto my work-desk. Most of them are museum pieces. Thus it is vital in their conservation that the used materials could be later removed from the object. The best way for achieving this is to use natural materials that have been used in conservation for a long time already. That is why my favourite stuff is Japanese paper (kozo and others) and wheat-starch paste. I mostly use 20g/m2 and 40g/m2 Japanese paper that is suitable for filling small holes (like moth- and nail-holes) and repairing losses that would be beneath the covering material (in bindings or drawers under corners or locks). Minor repairs are done for textile also, when a drawer’s or a case’s interior lining needs mending at the back.

Thanks to the good adherence of Japanese paper and the strength of its fibre it is good for conservation in company with suitable glue. It is a bonus that, if necessary, the repairs can be later removed as well.

REFERENCES:

1.Japanese paper 40 and 20g/m2 was used for modelling losses or tears and 5g/m2 for filling the surfaces layer by layer.

2. The oldest museum pieces of the Estonian History Museum come from its predecessor – the Estonian Provincial Museum that was established in 1864 and based on the private collection Mon faible that Johann Burchard had set up in 1802. The present work deals with the Egyptian sarcophagus for a cat’s mummy (AM5896) dating back to 600 BC – 200 AD. The object measures – 29cm x 31.5cm x 15.5cm and its materials are wood, textile, clay and polychrome paints.

3. An analogous figure dating from the 26th dynasty or the late period (664-525 BC) can be found on the home-page of the Hecht Museum, University of Haifa:

http://mushecht.haifa.ac.il/archeology/egypt_eng.aspx (01.12.2009).

The National Museum of Antiquities in the Netherlands keeps two sarcophagi of cats with mummies inside. The National Museum (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) was established on the collections of Leiden University. The museum has a rich collection of Old-Egyptian, Middle-Eastern, Antique Greek and Roman art: http://www.rmo.nl/(03.12.2009). The Egyptologists of the museum confirmed that our History Museum’s object is indeed a sarcophagus for keeping a cat’s mummy. The sarcophagus has an exceptionally detailed painted decoration, a big medallion and a good-quality base that all let us believe that it is a rare and expensive piece. (Based on the correspondence with Estonian archaeologist Heiki Pauts, who worked at the Estonian History Museum up to 2001.)

4. Stuffed crocodile from the Estonian Theatre and Music Museum. Measurements: 99cm x 26.5cm x 19.6cm. Materials used – crocodile skin, wood shavings, synthetic string.

5. Stuffed lobster, private collection. Pink spiny lobster of Mauritania, Latin – Palinurus mauritanicus Guvel, 1911. Measurements: 40cm, width – 26cm, 10.5cm: carapace – 36.2cm x 22cm x 9cm. Materials used – chitin, cardboard, string, metal.

6. Anion-active paints Fastusol. (Gabi Kleindorfer, Germany)