PRESERVATION OF ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS IN PHOTOCOPY TECHNIQUE

Autor:

Tea Šumanov

Anno 2019/2020

Category:

Research

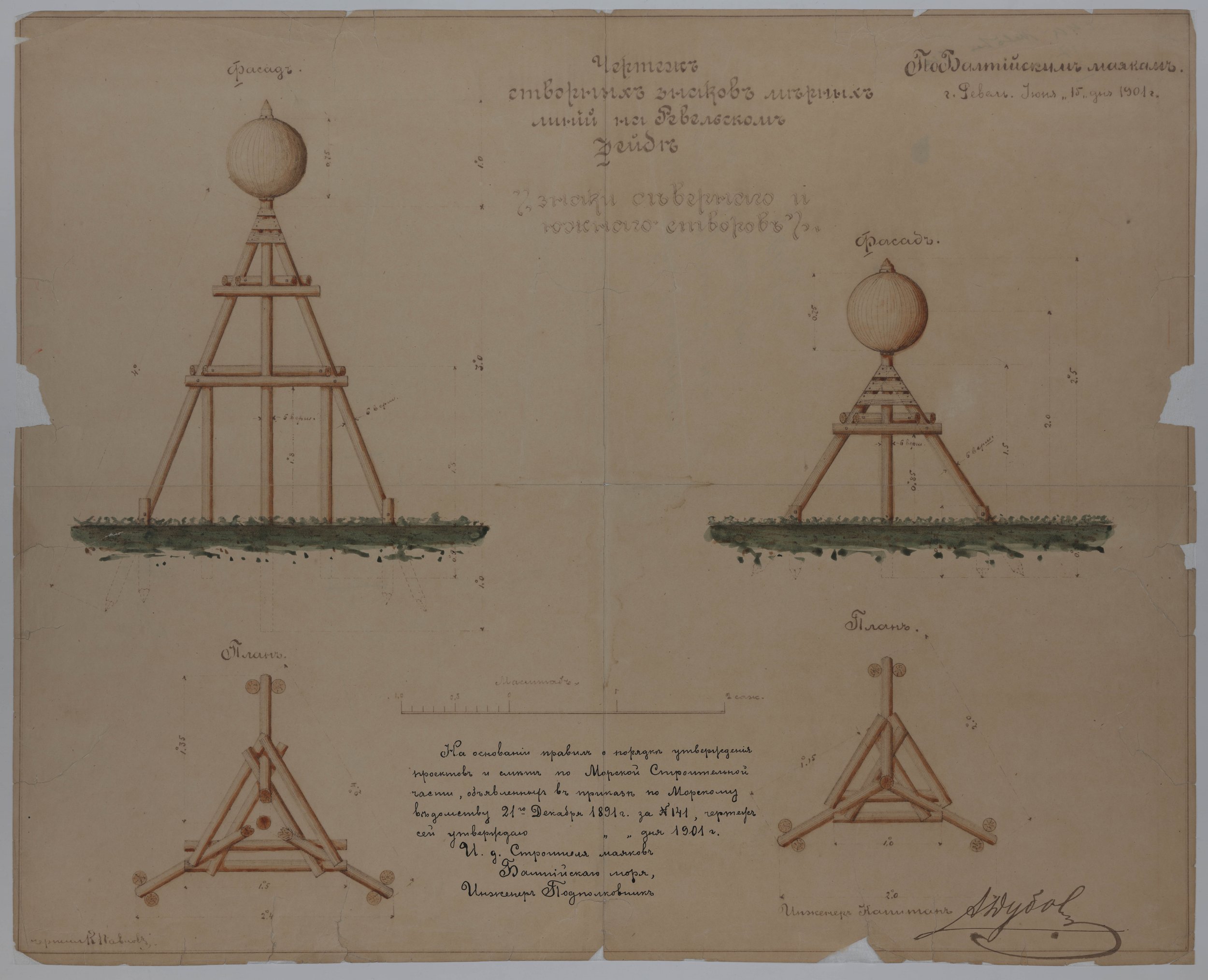

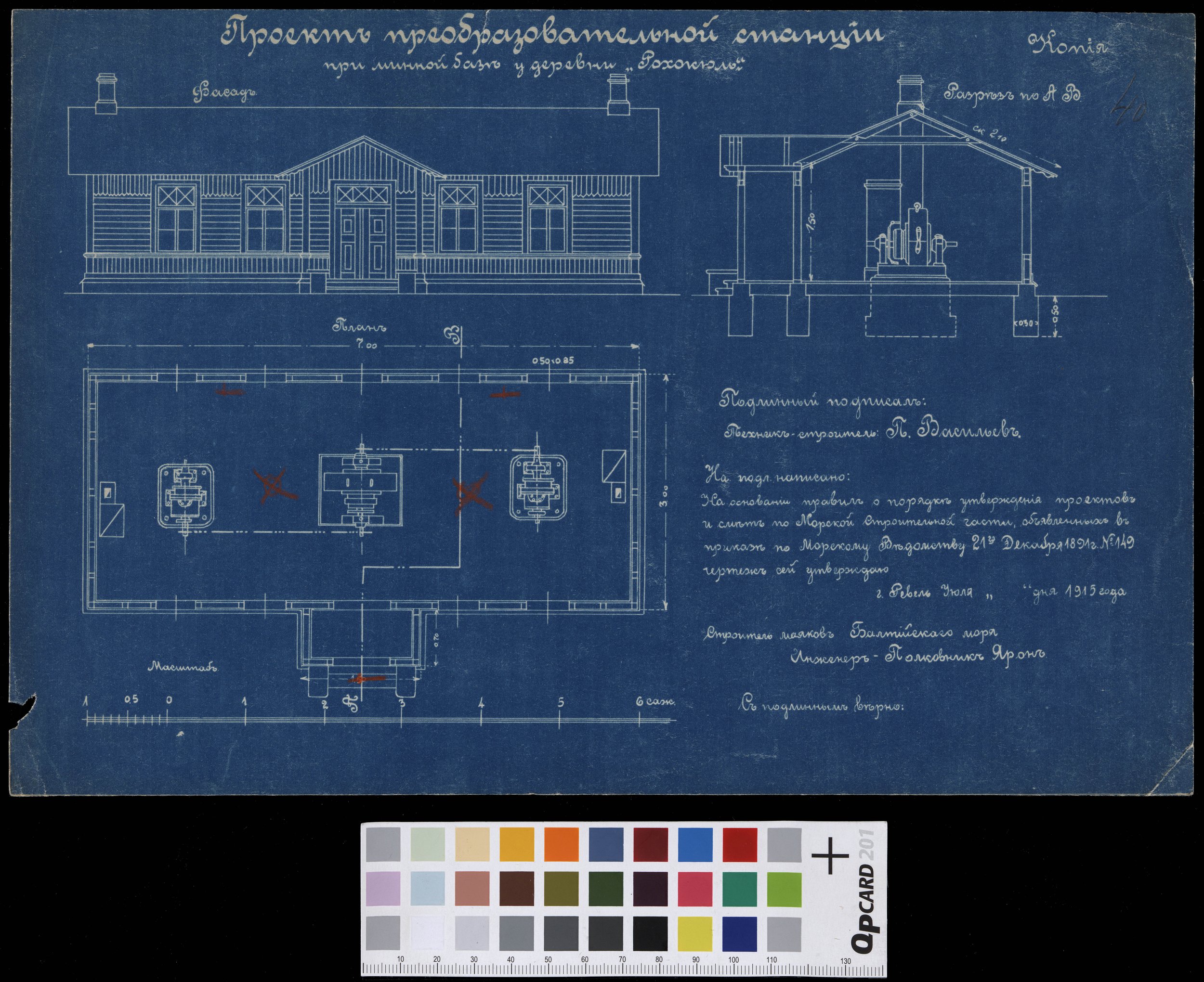

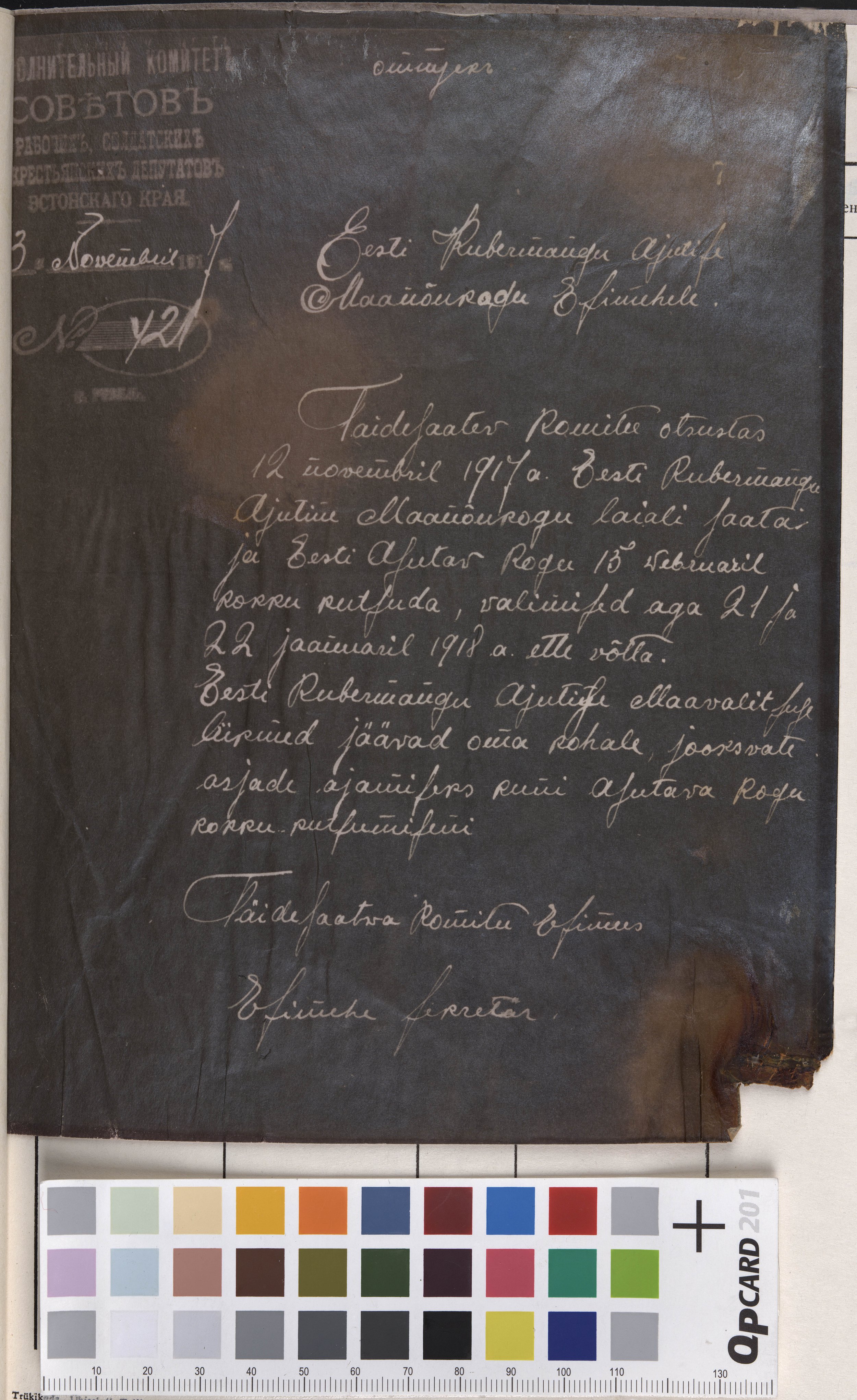

Obviously every archive that keeps architectural drawings also stores copies of them in various techniques. The need for copies became apparent in the 19th century, when industry and technique were in rapid development and projects kept getting more complicated and detailed all the time. Many more people were engaged in construction and it became impossible to copy drawings by hand as quickly as they were needed. Beginning from that time, people sought better solutions for copies of quality reproduced cheaply and quickly. Photography techniques were followed as models. One of the most successful techniques invented at that time was cyanotype or blueprint method. [fig 1] The second term was taken into use as a general concept denoting a reproduction of a drawing in whatever technique. In Estonia the notion in parallel use was photocopy. Preservation of drawings in this technique is rather problematic, as, due to their chemical processing, they demand special conditions for conservation, storing and displaying.

The present article focuses on copying techniques introduced in the second half of the 19th century. They were in use throughout the first half of the 20th century, i.e. before the xerographic techniques were introduced. (1) The author explains how the topic became acute for her and what steps have been taken for better maintenance of the copies. It is discussed why it is vital to identify the copying technique for better storing.

Research

It started for me just as it had started for Lois Price (2) , the author of the book Line, Shade and Shadow. I was ‘activated’ because I was not familiar with the materials and doubted a lot when I had to make decisions for their conservation.

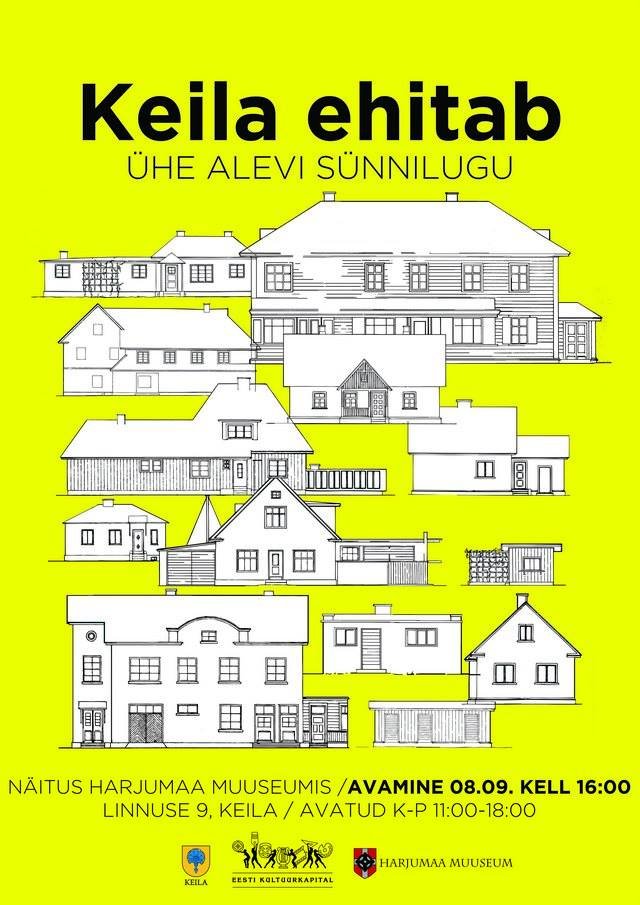

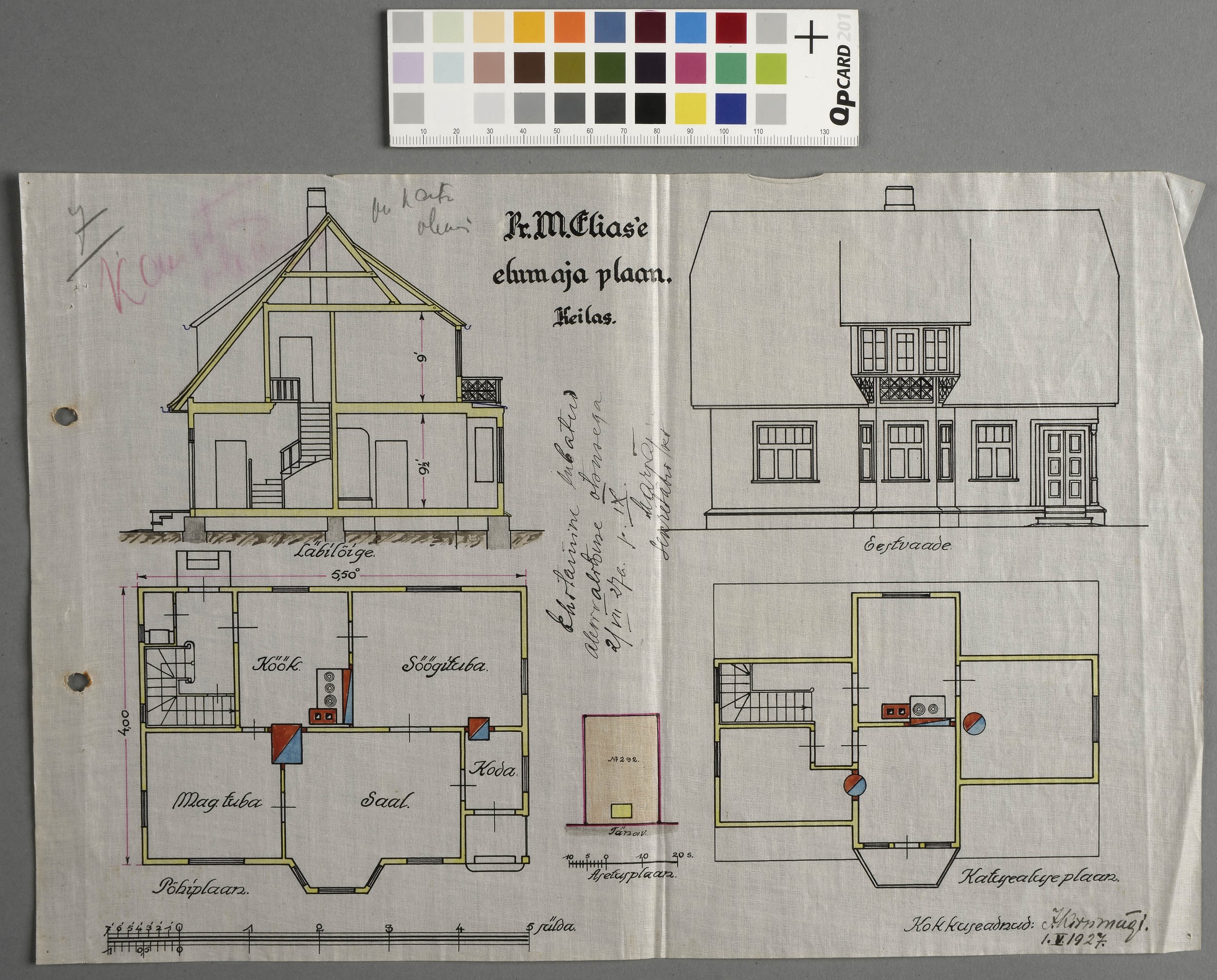

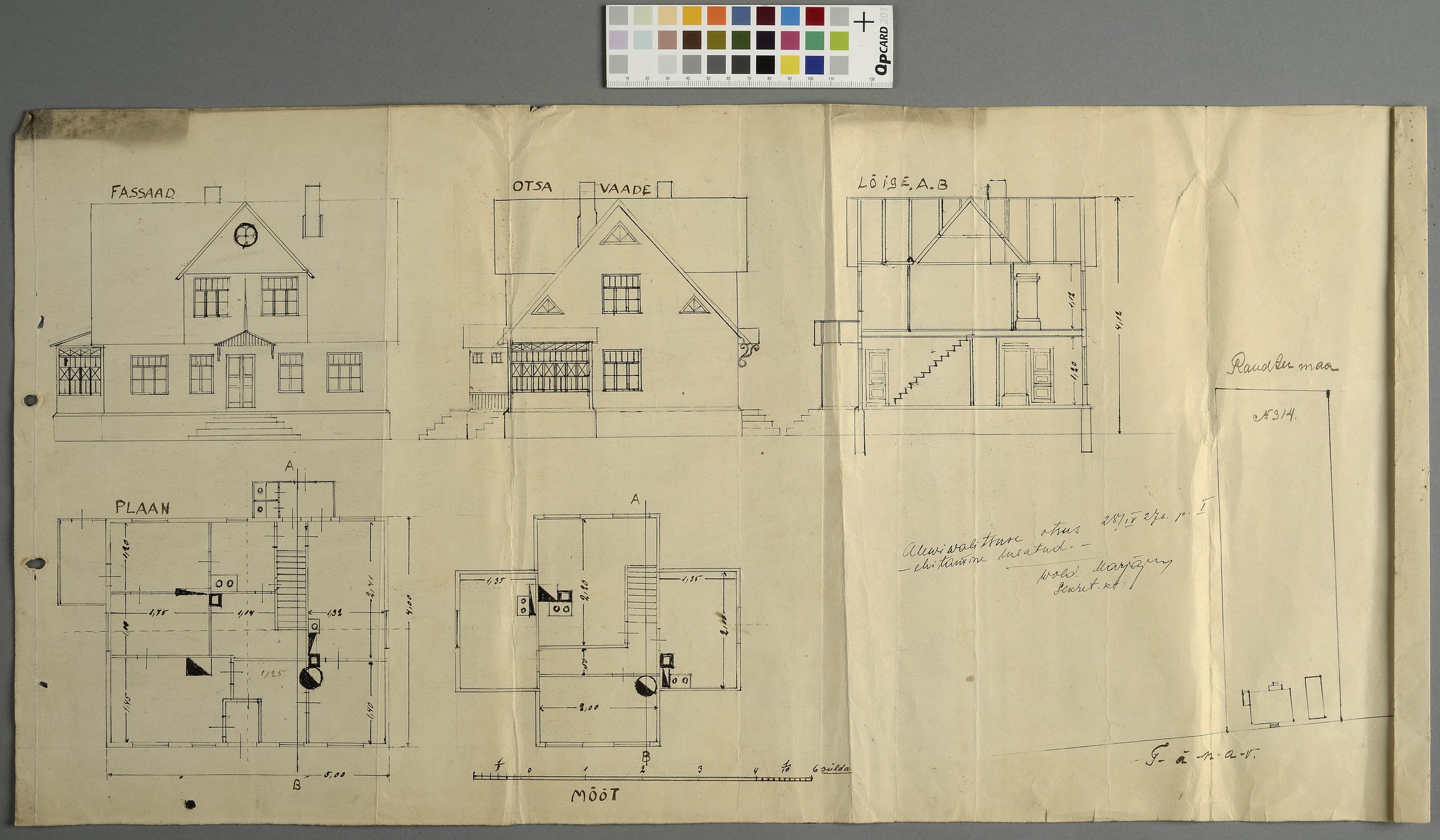

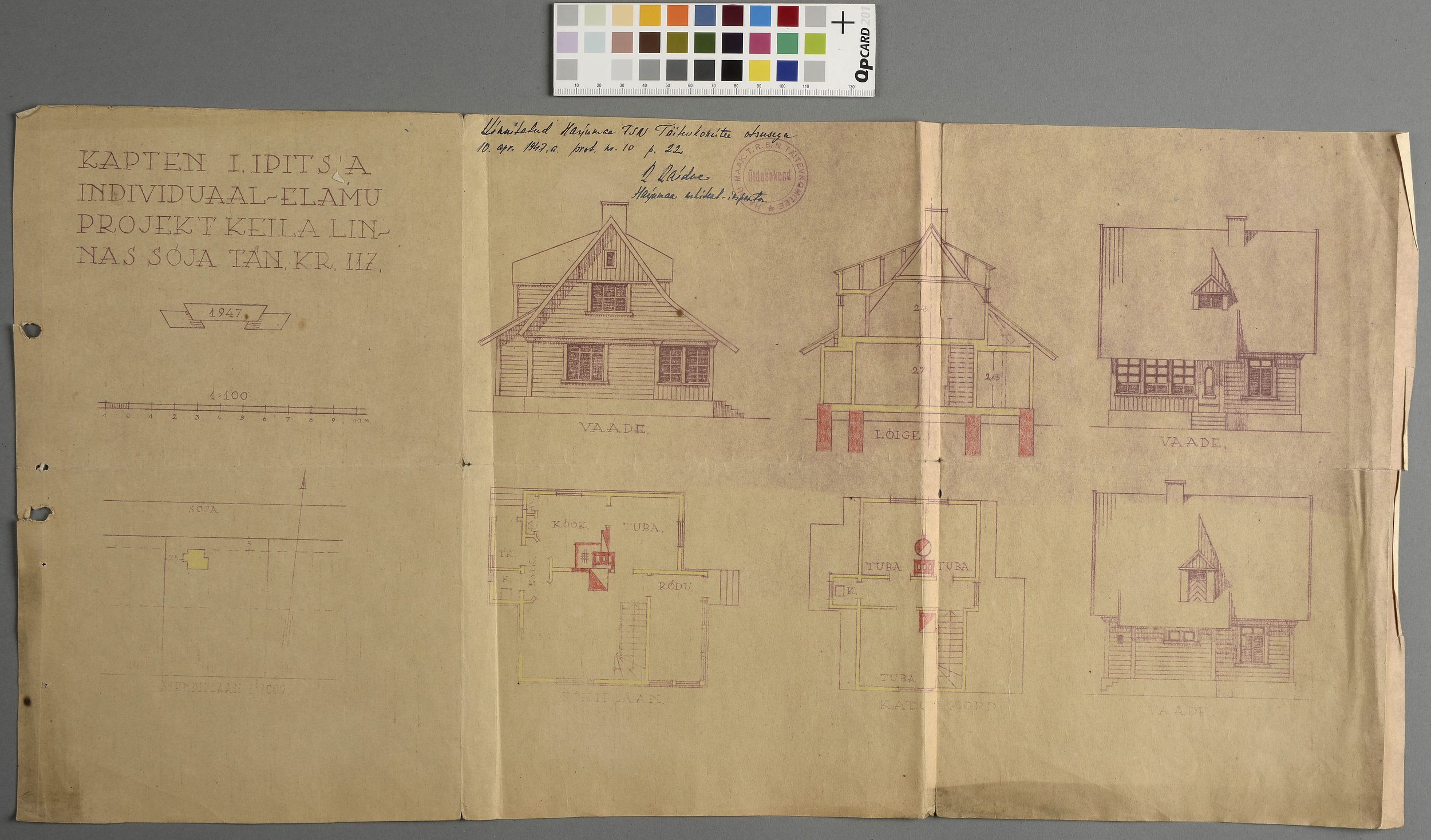

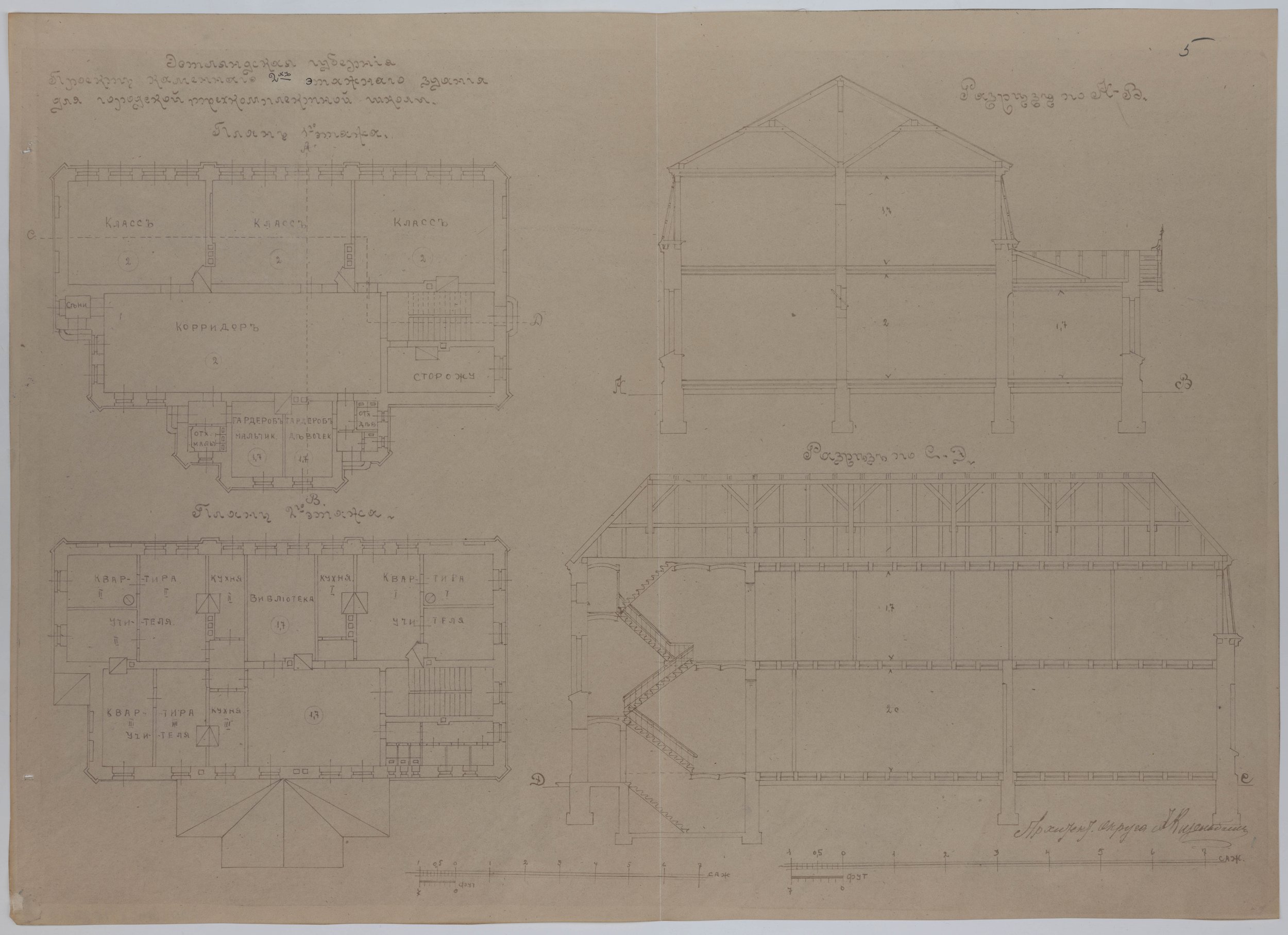

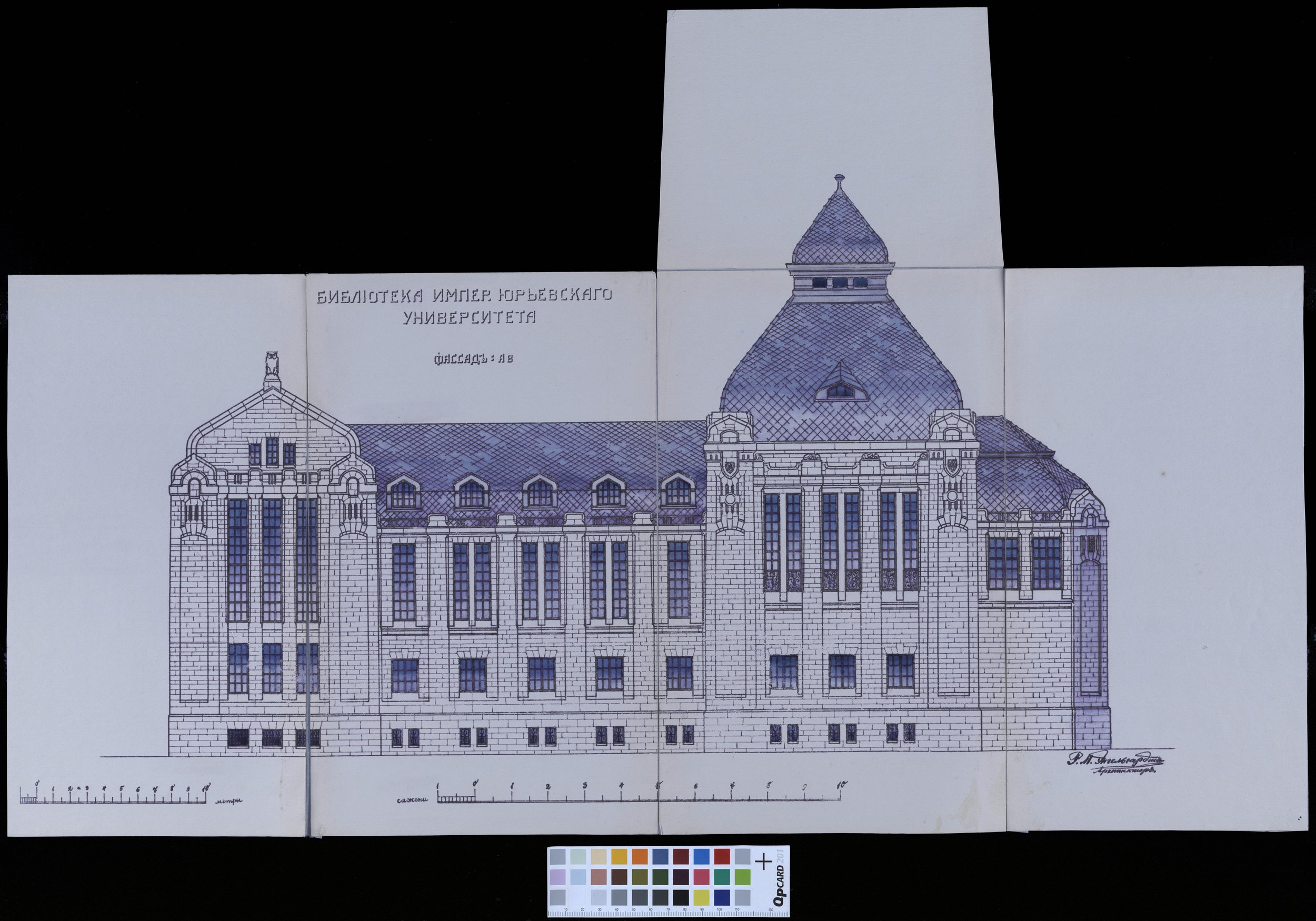

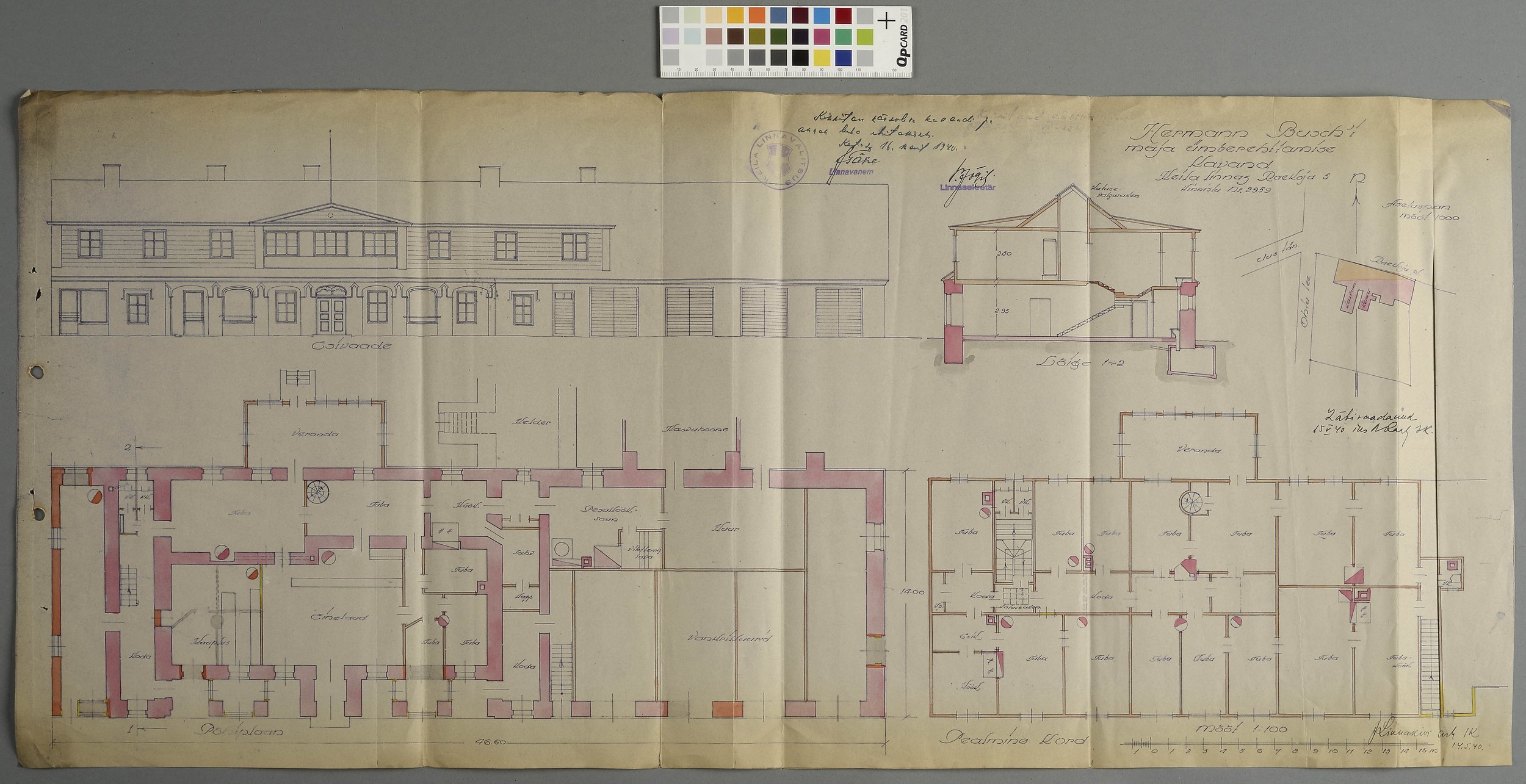

I had no idea yet what interesting research was waiting for me, when the Harjumaa County Museum sent a set of architectural drawings to the Kanut in 2015. They had to be prepared for the exhibition Keila is building – the story about the birth of a township. [fig 2], [fig 3] The set consisted of plans of houses built in 1920-1940. There were 165 designs in all, drawn on tracing paper, textile tracing paper and paper. [fig 4], [fig 5], [fig 6] The majority of them, though, were copies. [fig 7] Providently it might be said that their characteristic features pointed at diazotypes. 45 drawings, in worse condition than the rest, were selected for conservation. Conservation of drawings on tracing paper and paper was not unfamiliar for the conservator, but the less-known copies brought along problems. The preparations for displaying the drawings included also the staff of the Harjumaa County Museum in Keila, who have published their experience in the journal Muuseum (2016).(3)

We attempted to identify the types of the copies but understood pretty soon that we lacked experience for that. We sought help in the Internet and asked around colleagues how photocopies have been reproduced. Several deliberations led us to the conclusion that the copies could be, depending on the technique, sensitive to light and moisture, acidic and image-fading and that is why they should be digitised first. (4)

After conservation the drawings were sorted out according to the techniques (copies, tracing paper ones, textile tracing paper ones and original drawings) to be sure, which storing-covers to commission and for picking out the objects most suitable to be displayed. The museum had intended to display its original drawings only, as they did not want to risk damaging copies sensitive to light. By chance, diazo-types were also displayed, as at first sight they had seemed to be drawings in China ink. The mistake was conceivable, as copies can be of very good quality indeed and quite often also coloured. [fig 8]. Actually, it was a profitable mistake that triggered the research.

Launching the research it was immediately discovered that bibliography on the topic was rather scarce. True enough, some excellent books in English [fig 9], [fig 10], [fig 11] had been published, but they did not answer all the questions concerning the work on my desk. It was impossible to find anything in Estonian, except a few booklets introducing copying techniques that had been published in the Soviet period. Consulting various curators and conservators of our memory institutions only emphasised the fact that knowledge was meagre, but the wish to learn more was great. Both, the Harjumaa County Museum and Kanut wished to determine what is what in their collection and to learn to present a correct description of the items. To help us out we needed to find an expert from somewhere outside Estonia.

Presenting the topic in workshops

It seemed justified to arrange a workshop with a foreign expert to give as many as possible museum- and archives-employees dealing with conservation and storing a chance to share the guest’s experience and know-how. The guest invited was Amandine Camp [fig 12] from France. Eleonore Kissel, one of the authors of the book Architectural Photoreproductions: A Manual for Identification and Care. (5) recommended her to us. Camp is a graduate from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne with an MA in conservation/restoration. She has a private studio in Avignon and among other assignments she works also for museums all over France. She obtained her first experience in identification and conservation of copies at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in 2013. Camp participated there in the preparation of the collection of architectural drawings, plans and models for the exhibition Casablanca-Chandigarh. The work included identifying a great amount of copies and testing suitable conservation methods and conditions for displaying, especially conditions of lighting.

Identification of photo-reproductions’ workshop called Preservation of the cultural-value photocopies, with texts that are degraded by time, in Estonian memory institutions took place at the Kanut on 19 October 2017.

The aim of the workshop was –

To draw attention to the photo-technical materials that have not been paid heed yet but what need the same kind of care as photos, slides et al. photo materials.

To introduce briefly noted reproducing techniques with characteristics that help to identify them.

To provide ideas and solutions for further decisions on keeping and storing, so that the researchers would gain access and the institution would have an opportunity to show them to the public.

One of the most important conditions to arrange the workshop was the existence of various examples of reproductions. The Kanut got the deposits from the Museum of Estonian Architecture, Estonian Maritime Museum, Harju County Museum and, in majority, from the Tartu department of the National Archives. The Ministry of Culture and Cultural Endowment sponsored the workshop.

Participants were conservators-curators of the Tallinn City Archives, SA Museums of Virumaa, Tallinn and Tartu departments of the National Archives, National Library, Museum of Estonian Architecture and Kanut.

Programme of the workshop

The day was divided into two parts. The first half was dedicated to introducing copies, their kinds, characteristic features and identification methods that were more widely spread in the late 19th until the middle of the 20th century [fig 13]. The drawings were visually examined with a magnifying glass and microscope [fig 14]. All in all, eight different reproduction techniques were identified: Ferrogallic prints [fig 15], Cyanotypes [fig 16], Vandykes [fig 17], Hectographs [fig 18], Diazotypes [fig 19], Sepia-diazotypes, Photostats [fig 20] and Gel-lithographs.

The second half of the workshop dealt with topics of conservation and care, in which selection of the right materials is the most essential problem. Reproductions in different techniques demand special materials and conditions for storing and displaying. They should not be stored in the same covers, as the materials of different chemical composition may decompose and produce decay in images. Even the common cleansing materials used in conservation may occur unsuitable. So, for example, one should not cleanse copies sensitive to alkaline materials (e.g. diazodtypes, cyanotypes and ferrogallic prints) with vinyl erasers [fig 19], [fig 16], [fig 15]. The quite well-known and efficient cleaning sponge would not do for materials sensitive to sulphur (e.g. Vandykes) [fig 17], as the sponge contains this chemical. Sponges and erasers are too abrasive and thus may scratch the surface of the image too much. This shows that the identification of the reproductions is extremely necessary for choosing the most suitable means and materials for conservation.

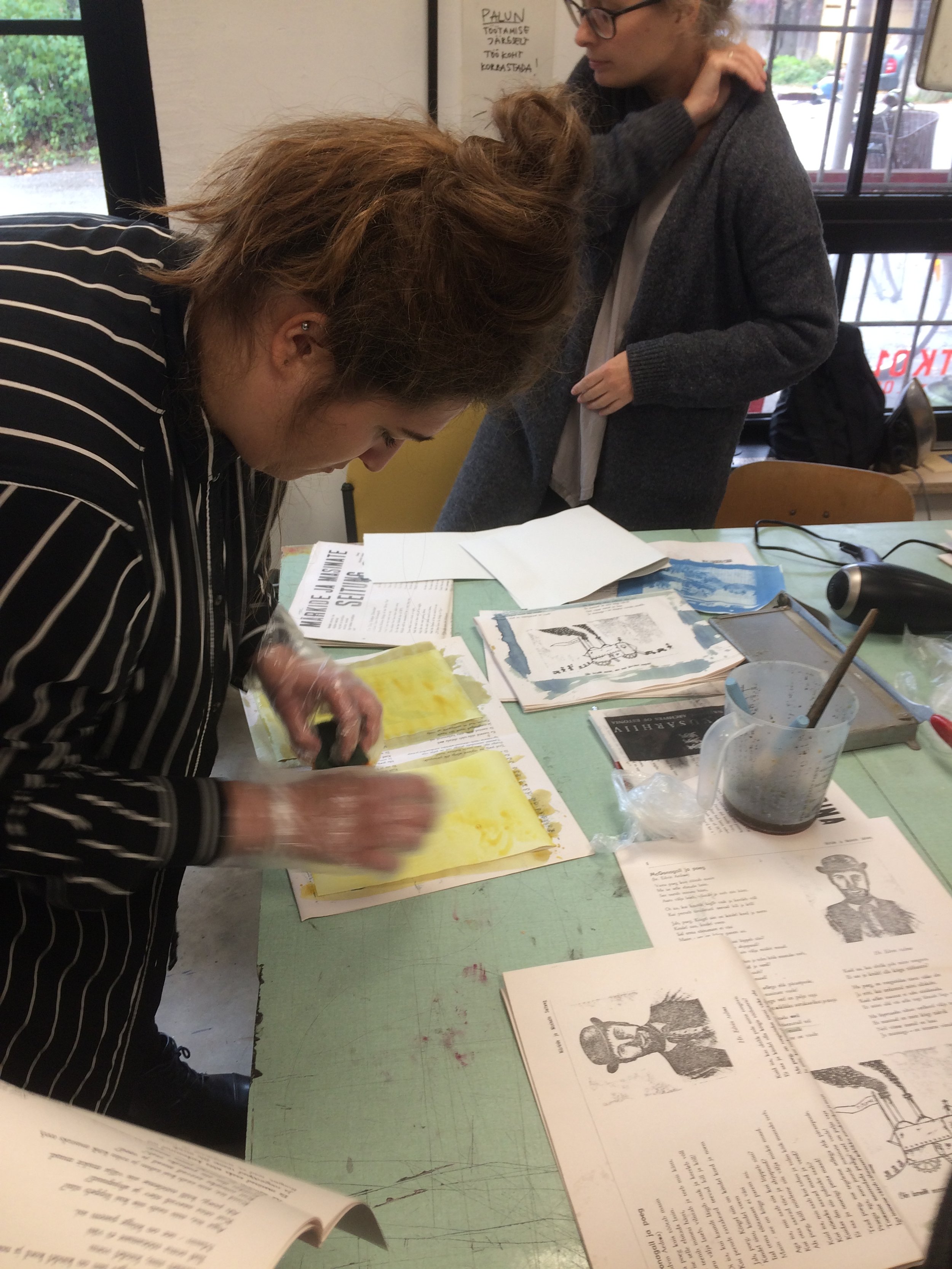

The practical part of the workshop included testing a cleansing method that is all right for all the reproductions – dry cleaning with a brush made of goat’s hair [fig 21]. Japanese brushes are soft and gentle in removing the surface dirt. Conservators doubted the effectiveness of the method [fig 22]. Our instructor stressed that the main aim was to remove loose dust [fig 23]. She advised the audience to avoid wet procedures (like washing and gluing), as reproductions were sensitive to moisture.

Identifying the technique of a reproduction

The identification of copies could be rather complicated, as there are several different techniques in use. Some of them may initially seem similar and some may seem to be originals made in Indian/China ink [fig 24]. It should be useful just to observe and train your eyes to separate the differences in techniques [fig 25]. This is an essential and non-destructive research method, as no pieces for testing are moved from the object. Several attributes can be discovered with a naked eye. The surest way, of course, is to examine the techniques with a magnifying glass and microscope.

Amandine Camp demonstrated a step-by-step identification method that she had used in her research identifying architectural drawings for Casablanca-Charigarh exhibition. This method is based on the methodology of James M. Reilly. (7) and consists of three steps.

Identify the surface aspect.

Determine its structure.

Finally, identify its own characteristics, while referring to the description of each process.

In addition to that she introduced the Kissel and Vigneau system that proposes to examine. (8)

The colour of the lines in the image

The character of the lines – are they on the surface of the material or deeper inside it (as if fused)

Characteristics of the background – is it clean or speckled, ‘dirty’, spotty (with residue of light-sensitive solution)

Looks of the support – is the paper fibres visible or not; is the surface calendered etc.

Condition of the support – e.g. copies in Ferrogallic technique may be fragile (damaged paper)

Characteristic degredations of certain techniques – e.g. in case of diazo-types changes in colour appear first on the edges of the sheet, the reverse side is lighter than the face and unvaried in tone

The time when the copy was made – the dates can hint at the use of certain technique at the time, but not that of the original document. Dates, stamps, etc. should be observed

Smell – e.g. diazotypes smell of ammonia

Manufacturer’s signs

Materials and conditions for storing

Copies/reproductions should be separated from the originals and also reproductions in different techniques should be kept separated. When the covers have been made, one should go on following the technique (see table 1). In case of sensitive copies materials with neutral pH according to the PAT test must be used. (9) The golden rule – when in doubt, keep separately – should be observed. Doing that you do not have to waste time on identifying the technique of every copy. When the object has already been identified as a copy, it would be safe to put it into folders with neutral pH and store it in an archival folder or case.

Table 1. Selection of storage materials

Unbuffered or neutral materials are suitable

Hectographs /Cyanotypes/Vandykes/Diazotypes/Ferrogallic print/Aniline print/Phtostats

Buffered materials are suitable

Tracing paper / Hand-made paper/ Canvas/ Electro-Fax; Xerox / Gel-lithograph (or gel-litho)/ Copies made with carbon paper

Displaying

Displaying conditions were introduced on diazotypes and cyanotypes (blueprints). Generally the greatest damage on copies is done by light. Tests made at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in 1997 showed that cyanotypes were most sensitive to light and thus not suitable for displaying. Diazotypes are to some extent more serviceable. They may be displayed for a short period, with controlled conditions of light (50 Lux).(10)

Workshop at the National Archives

Workshops that had started with the preparations for the Harju County Museum´s exhibition ‘about neglected and unvalued heritage of culture’ continued in 2018. The workshop arranged by the National Archives and titled Identification and Care of Architectural Drawings and their Reproductions took place in the Noora building of the National Archives in Tartu, on 25-28 September 2018. Amadine Camp saw it through again. After the 2017 workshop at the Kanut the National Archives had recognised the necessity of longer and more detailed workshops, one day had certainly not been enough. The basic plan of the workshop was more or less the same as that of the first one but much more detailed. First of all the history and technical peculiarities of reproduction techniques were presented. The second day was dedicated to the identification of copies. The first half of the day introduced characteristic features of techniques that were the key for identification. It goes without saying that the reproductions from the National Archives were used for that. After that work-groups had to identify a certain selection of copies and it was quite exciting to watch them searching answers in their notes and have a lively discussion. About ten techniques were included and it was not a piece of cake to remember everything at once. Finally the work was checked up and a general discussion took place. These discussions were interesting and useful, as everybody had to explain and ground their choices, so the new information was perpetuated.

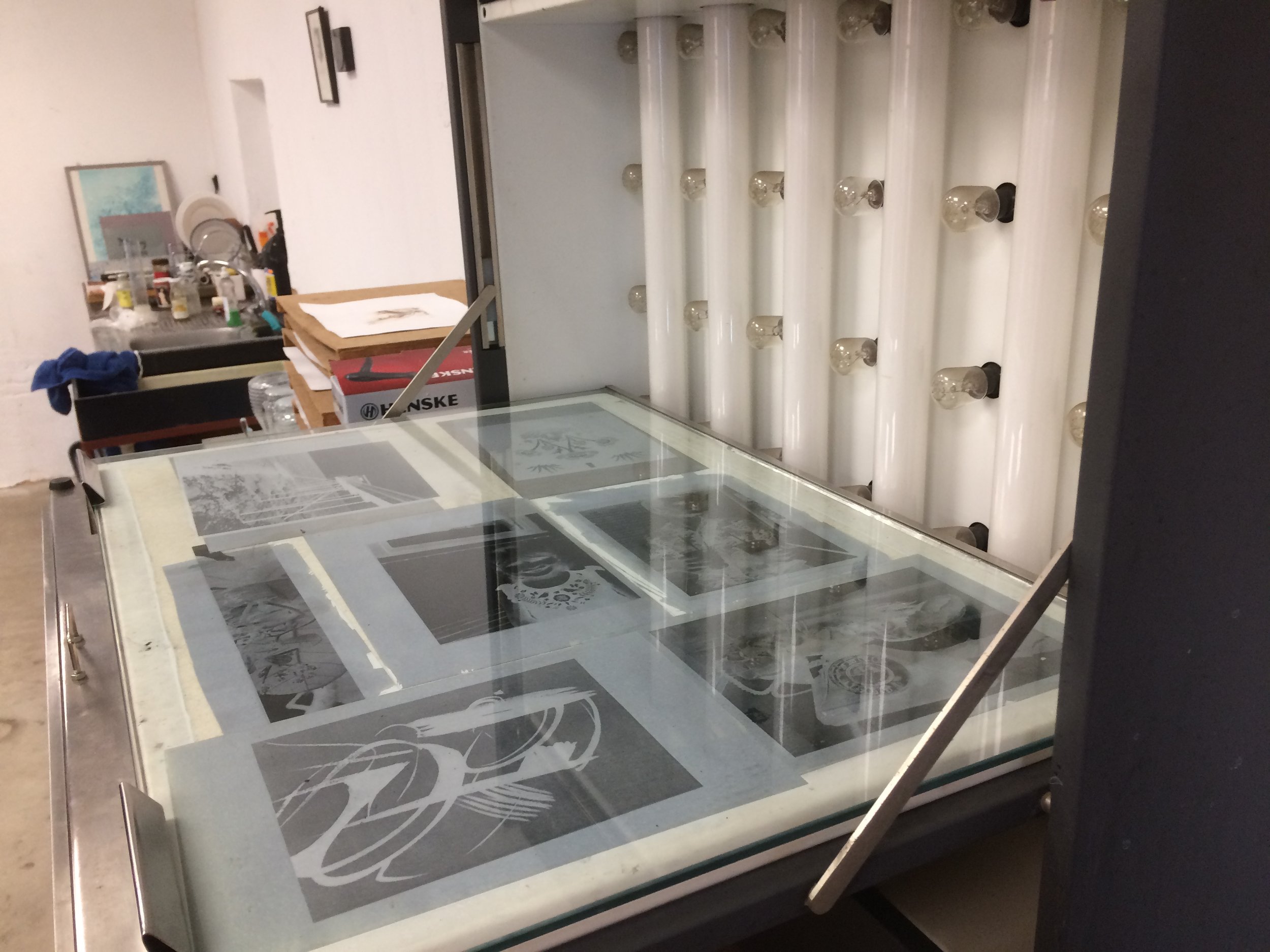

The third day witnessed problems of conservation, storing and suitable conditions for displaying. After the talk everybody could choose one reproduction for cleaning, stretching and repairing. First of all the technique was to be identified, as the selection of implements depended on that. The fourth day was at the Estonian Print and Paper Museum and focused on cyanotypes [fig 26], [fig 27], [fig 28], [fig 29].

Summary and plans for the future

Copies present a far more complicated kind of objects as seen at first sight. Storing them, they should be treated as photos because this is what they actually are. Further keeping, handling and displaying them in proper conditions all depend on their techniques and the skill to identify them.

Interest in workshops proved that the wish to do it is great. A new problem, however, has appeared – how to grant storing and keeping with proper care and right methods? Do our museums and archives have output enough to deal with the identification of reproductions when their workload is heavy already? Could it be made a little simpler for the curators and conservators? The author of this article is also interested how problematic the keeping of copies in various techniques in our collections actually is. To search answers to these questions I have chosen this problem for my M.A. thesis that I have decided to defend at the heritage and conservation department of the Estonian Academy of Art in 2018-2020.

REFERENCES:

1. Xerography or ‘dry writing’ is one of the electronic copying methods that transfer the image through a middle element (like selenium plate or -cylinder). The process is made up of five basic operations: 1) making the xerographic plate sensitive to light; 2) exposing the image; 3) developing the image; 4) transferring the image from the plate to the support material; 5) fixing the image onto the paper. The method was first introduced in 1938 in the American physicist Chester F. Carlson’s patent on electron photography. – E. Vatter. Ülevaade kaasaegsetest kopeermenetlustest. ENSV Teaduslik-Tehnilise Informatsiooni ja propaganda Instituut. Tallinn, 1969, p 20.

2. L.Olcott Price (2010) Line, Shade and Shadow: The Fabrication and Preservation of Architectural Drawings, New Castle, USA: Oak Knoll Press

3. L. Serk ‘Argiarhitektuurist’ ja konserveerimisest. 165 ajaloolise majaplaani lood. – Muuseum 2016, no1 p 50

4. Conversations with conservators from the National Archives, Estonian maritime Museum, digitisation department of the Kanut in 2015-2016. (notes in the possession of the author)

5. E. Kissel, E. Vigneau (2009).Architectural Photoreproductions: A Manual for Identification and Care. New Castle, USA:□Oak Knoll Press and the New York Botanical Garden.

6. https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/events/3338/how-architects-experts-politicians-... (viewed 2019).

7. M. Reilly. (1986) Care and Identification of the 19th-Century Photographic Prints. Rochester: Eastman Kodak Company.

8. Amanda Camp’s teaching materials, dated 2017. They were modelled after Eléonore Kissel and Erin Vigneau’s identification system in the book Architectural Photoreproductions: A manual for Identification and Care. New Castle, USA:□Oak Knoll Press and the New York Botanical Garden. (2009), beginnig on p12.

9. PAT (Photo Activity Test) on photo activity, (Photo Activity Test ISO 18916:2007. Paper on polymers (polypropylene, polyester) have been tested and specially prepared for storing in a photo archive. The covers do not contain harmful chemicals, plastificators or acidic compounds. They protect the objects from fading and do not cause spots or damage on the originals.

10. J.Koerner, K. Potje. Testing and Decision-Making Regarding the Exhibition of Blueprints and Diazotypes at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. – The Book and Paper Group Annual 14 – http://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v21/bp21-06.pdf (viewed 2019)