Silk, feathers and great aims. The story about history, restoration and conservation of a furniture-set from the Kadriorg Art Museum

Autor: Tuuli Trikkant

Number: Anno 2022/2023

Rubriik: Conservation

When dealing with historical furniture we often have to face the dilemma between conservation and restoration, i.e. whether to repair or preserve. Historical upholstery or padding consists of many layers of natural materials like eelgrass, horsehair, various fabrics that all are susceptible to the dust, moisture, mildew and vermin. The wadding dating back to decades and sometimes for centuries is generally worn out and ragged. However, more often than not, these layers maintain invaluable information about materials, techniques and functions of the items. Thus repairing pieces of furniture without opening up the stuffing is complicated and rises several questions. How much of the original quickly disintegrating material would be possible to preserve and how should it be done? Could the piece lose its historical value when the layers beneath the seating material are opened? How were the previous stages of work processed?

The origin of the pieces of furniture is often unknown, the existing photos are few and memoirs even scarcer, whereas branding or labelling furniture was not practised in the past. Many a piece of furniture has lost its story with time, many have perished and so furniture with a past is rare in Estonia. That is why it was such a pleasure to be a witness to the opening of a small part of history, as it was done in our case. Some pieces from the foreign set of furniture belonging to the Kadriorg Art Museum viide1 ⁽¹⁾ were brought to me in December 2018. [ill 1] The sofa and two armchairs [ill 2] [ill 3] [ill 4] are a part of a bigger suite that also contains four easy chairs (with hard backs and padded seats), a table and two gilded richly-carved pedestals. The pieces, dated to 1876-1900, were made at the Melzer Furniture Factory in St Petersburg viide2 ⁽²⁾. The suite was brought to Estonia in the 1930s. It was to furnish the drawing room in the palace that was then the residence of the president. The end of the independence in 1940 brought along new ideas and taste also for furniture and interiors. Many an old piece was used for heating and several were given to theatres for props. The armchairs of the set under discussion were given to the Tallinn Drama Theatre that stored them in the Suur-Sõjamäe property depot together with many other pieces of furniture declared unsuitable from the ideological point of view.

In connection with the Olympic regatta in Tallinn in 1980 the armchairs were lent to the press bureau in Olympic Centre.

Earlier conservation

The armchairs were returned to the Art Museum in 1981. Restorer Mati Raal remembers that when the armchairs had already been taken into the bureau, the doorframes of the rooms had been changed and the chairs could not be taken out again. The solution was to saw off one of the back legs of each chair. viide3 ⁽³⁾

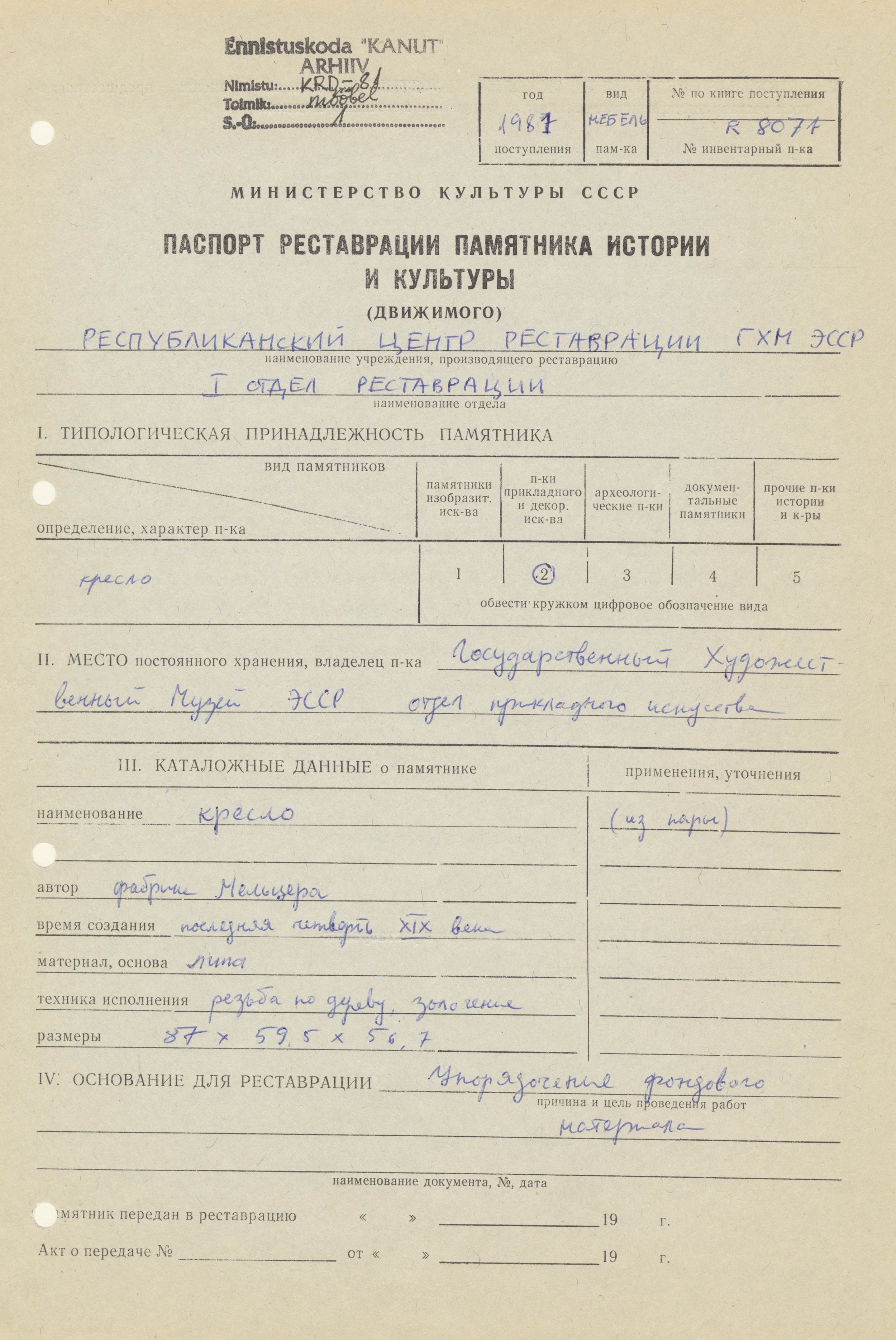

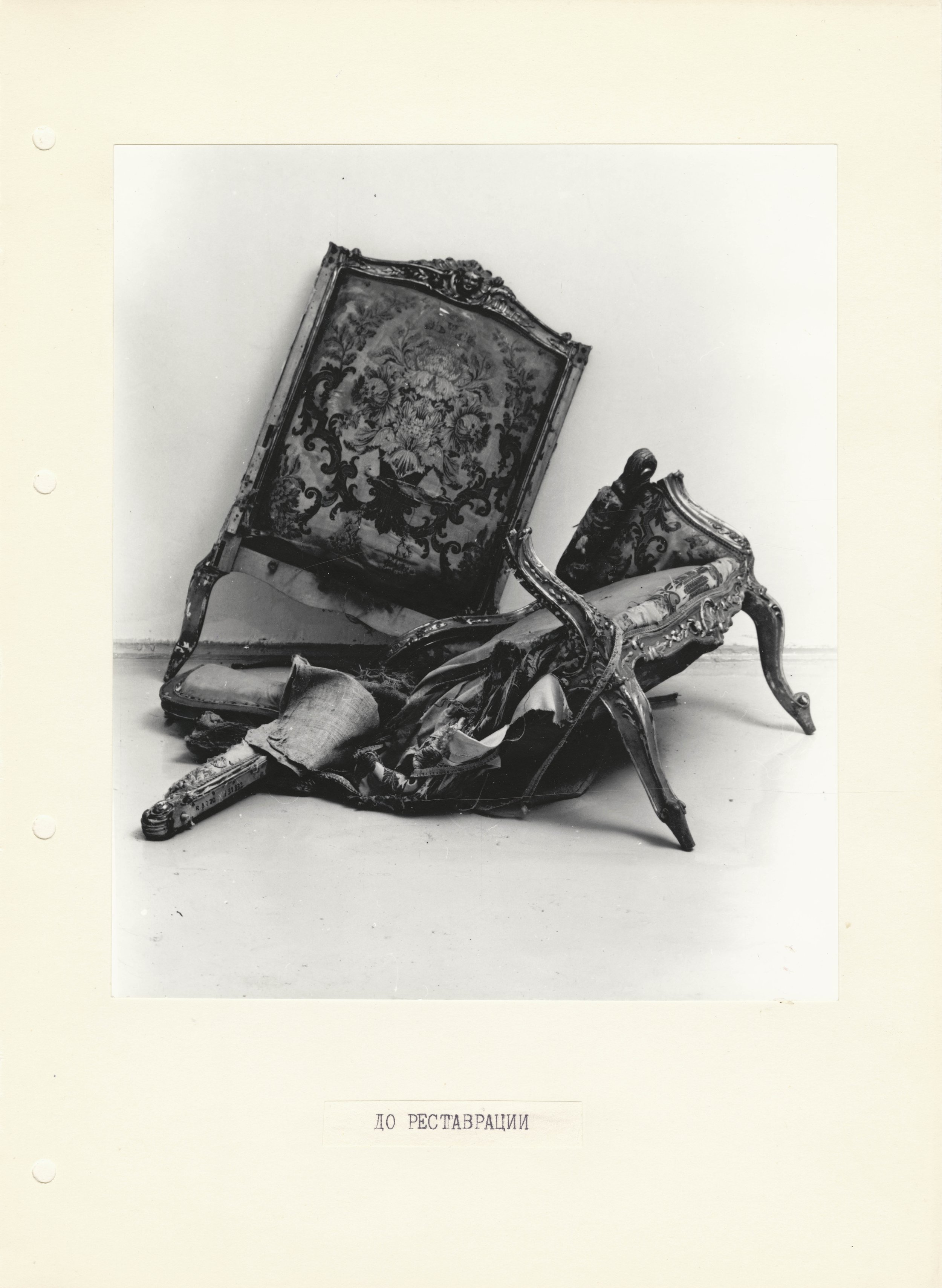

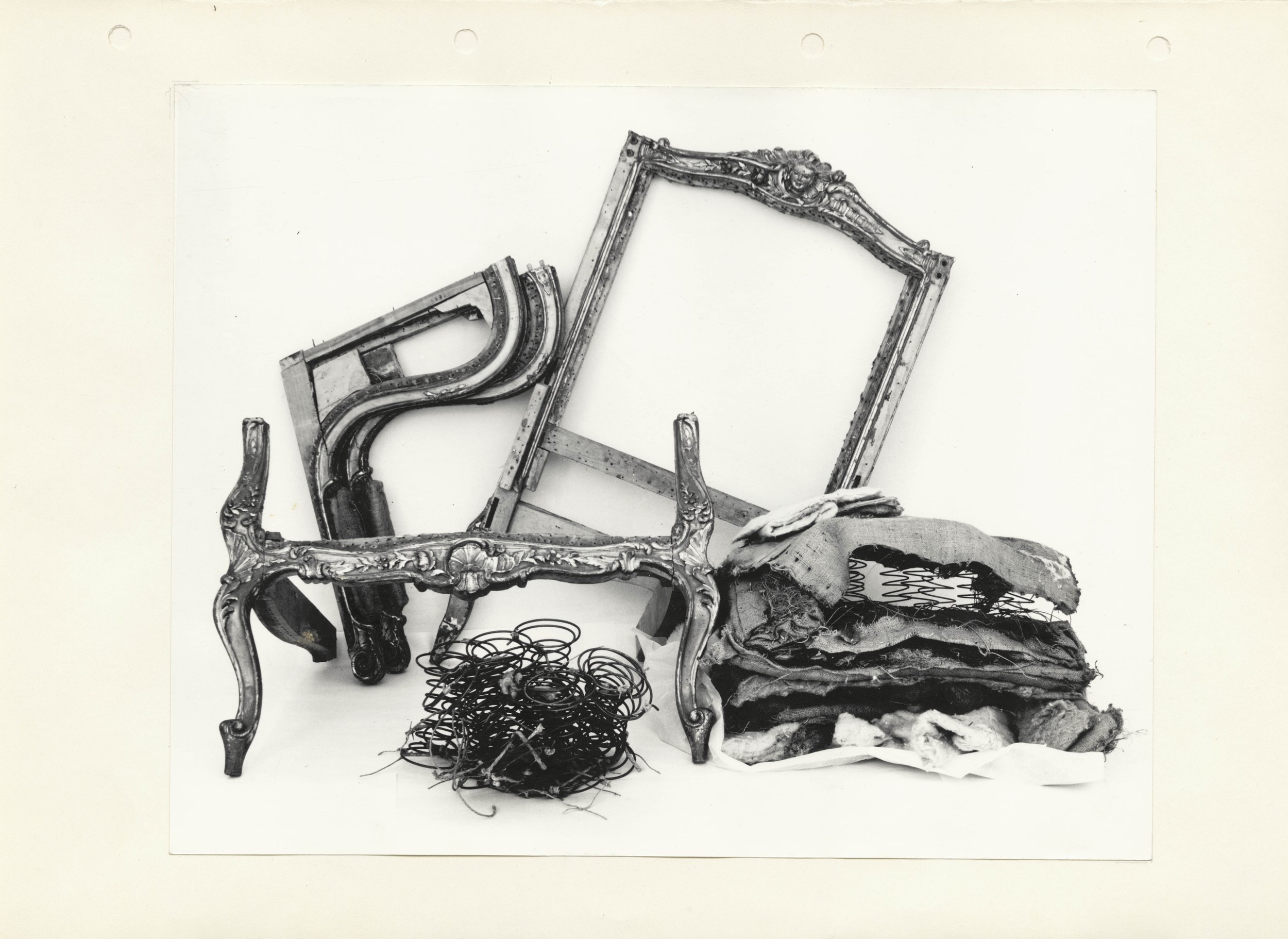

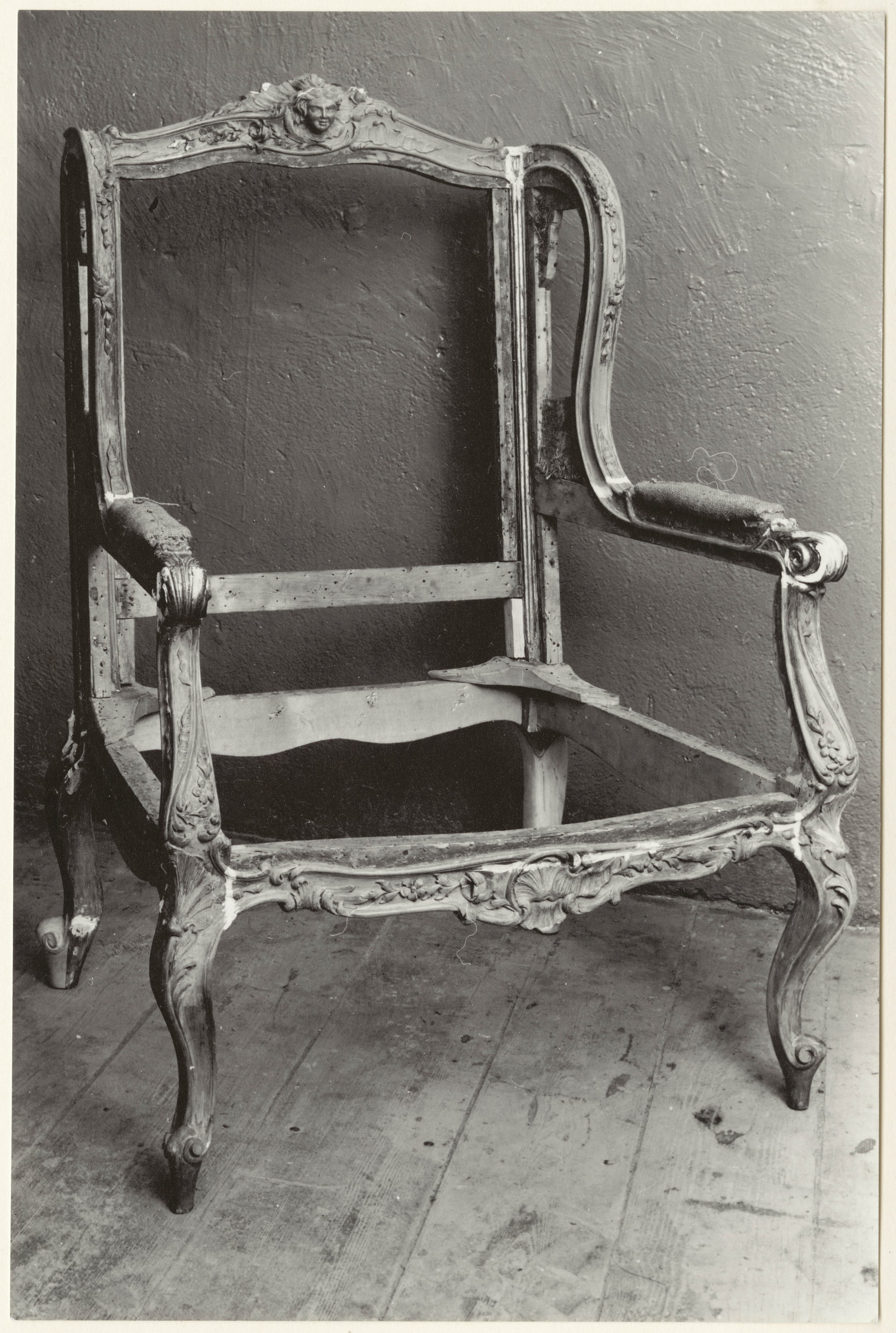

The armchairs were restored in the Republican Restoration Centre (‘Kanut’ today) in the second half of the 1980s by Mati Raal and Jaanus Heinla. The manuscript of the restoration, photos included, has preserved in the archive of the Kanut. [ill 5], [ill 6], [ill 7], [ill 8] An excerpt of a document describes the condition of the chairs as follows: “The armchair was broken when delivered. The left ear had broken off and some details were missing. One back leg was loose at its tenon. The other back leg had lost its foot. Due to the bad condition of the framework the soft seat, the lining of the back and elbow rests was damaged. The fabric on the back has become mouldy due to moisture. The material of the damaged elbow rests is torn and deformed. The springs have sunk through the bottom. The armchair was evidently coated with leaf-gold but very little of the gilding has survived – some traces could be detected on the inner side of one front leg. Later on the chair had been coated with bronze paint that has partly come off together with priming. Traces of timber-moths were not found.” viide4 ⁽⁴⁾

Although the damage of both armchairs was similar, the methodical approach to restoration differed. As the practices to conservation and restoration have changed since then it is difficult to assess the decisions made in the past today.

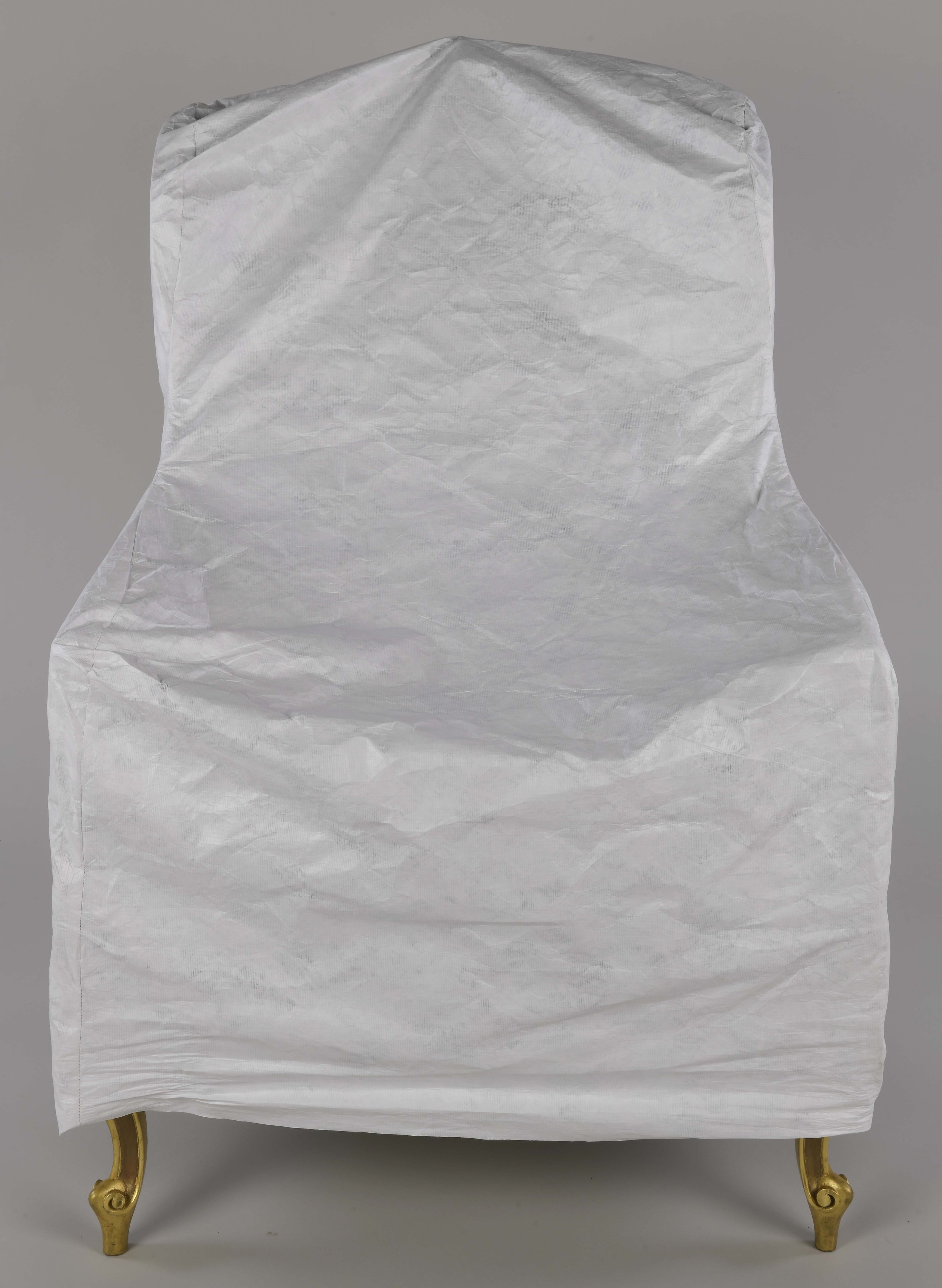

According to the restoration committee’s decision one armchair (further on ‘the blue armchair’ for clarity) [ill 3] got a new padding that was covered with a suitable rococo-style patterned fabric. New wool wadding was made for the seat. The wooden parts of the armchair were left as they were, even the back leg was not finished. The other armchair (‘the white armchair’ further on) [ill 4] got a fresh finishing with leaf-gold and finishing paste Goldfinger on all wooden parts, new details included. The fabric on its back was conserved. viide5 ⁽⁵⁾ This chair got a reconstructed stuffing – the back was overlaid with new fabric, the rest was left under white cotton fabric and the seat padding was not provided.

The second act in the assignment

The armchairs, together with the sofa this time, were brought to the Kanut again at the end of 2018. The museum wished to display the set. The earlier different approach to the reconstruction of the chairs and the poor condition of the sofa that was the most interesting piece of the three for research caused a lot of problems to be discussed with specialists of different fields.

Conservation of the padding and the preserved original fabric of the sofa were a challenge indeed. The same is true about strengthening the construction and the restoration and finishing of the missing wood-carved details. The most complicated of all was to find suitable replacement fabric for the losses in the seating material and unifying the finishing of all the three pieces.

Restoration of wooden parts

As the construction of both armchairs was in good condition it was not necessary to restore that. The sofa, however, had losses and breaks in its carving and its joints had become loose at tenons. [ill 9], [ill 10] The sea-shell ornament on the back had broken and some tips in the carving were missing. [ill 13], [ill 21] The end of the right front foot was a couple of centimetres shorter, the ‘ears’ of the arm supports had losses in carving and construction. Mechanical damage and signs of wear were visible on arm supports. [ill 11], [ill 12] Smaller details were loose or missing, the surfaces under losses had been toned in earlier restoration.

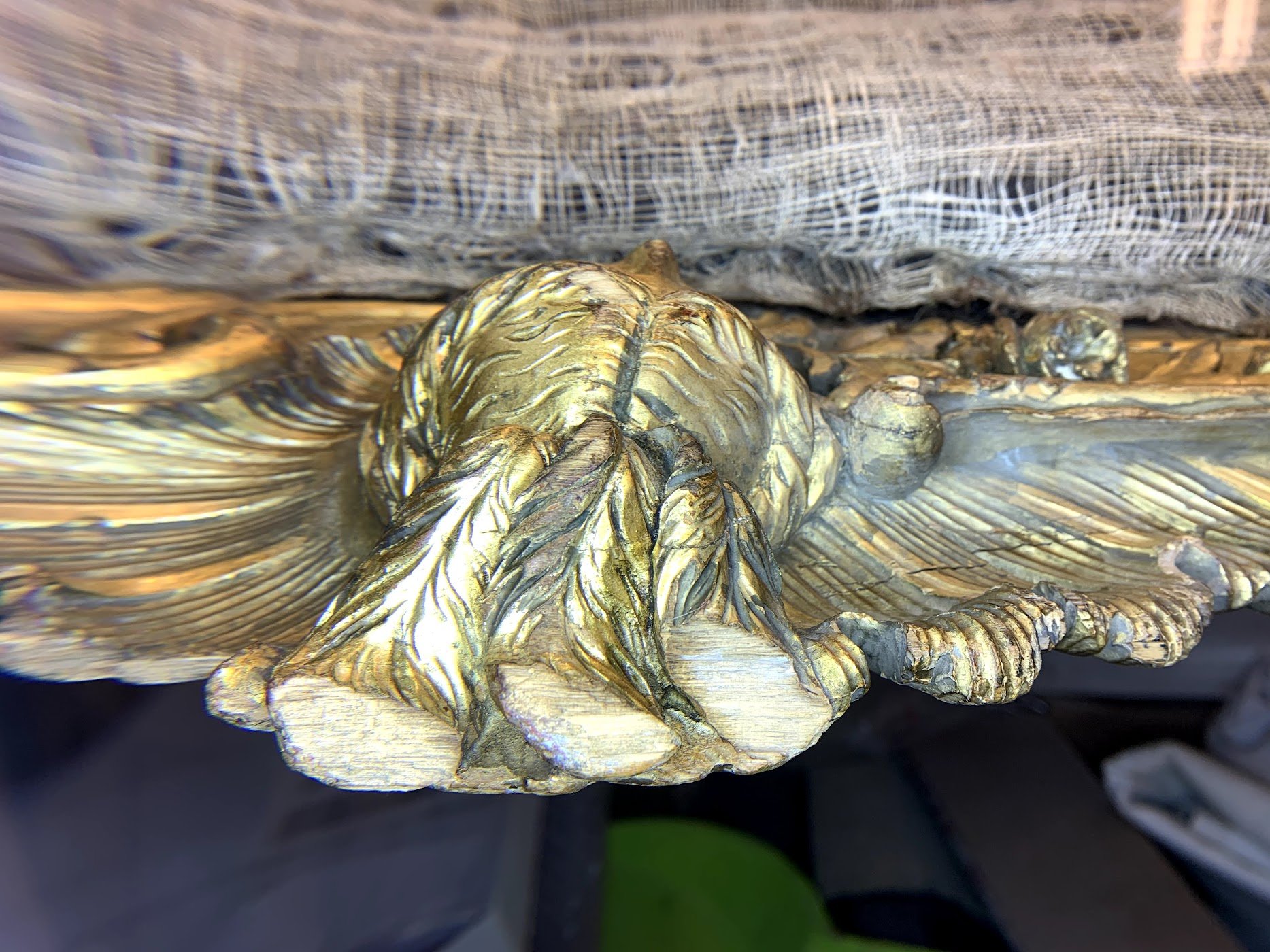

For restoring the missing carved details [ill 22] [ill 23] [ill 24] I used birch-wood and chisels. I restored only the details the missing of which marred the integrity; smaller losses were only toned, following the earlier practice. I used Titebond Genuine Hide Glue for construction and Titebond Original Wood Glue for repairs. [ill 16], [ill 17], [ill 18]

Equalising the finishing of wooden parts

It was quite a challenge again to equalise the finishing of all the three pieces of furniture. Their finishing revealed various layers of restoration in different times and as the pieces had been stored in bad conditions for a long time, the finishing on higher carving was seriously damaged or even lost. [ill 19] It was also partly crackled, especially in the lower parts and legs, where priming underneath gilding had chipped loose on the edges. First of all I cleaned the surfaces with 5% tri-ammonium citrate aqueous solution. [ill 20]

The wood as well as the fabric of the blue armchair and the sofa revealed traces of gilding. It hinted at the initial use of leaf-gold on higher surfaces, or on the so-to-say framing parts. It was visible that the hollow surfaces had been coated with bronze paint. For both armchairs restored in the 1980s all new similar wooden details had been made but the finishing had been solved in a different way: the white chair had got a new finishing, while the finishing of the blue one remained unchanged. The finishing of the sofa was more like that of the blue chair but it showed earlier toning and uneven repairs with leaf-gold and bronze paint here and there.

It took time and several discussions before we could decide which kind of finishing should be chosen. It was a problem to unify different surfaces so that as much of the original as possible would survive. The concave surfaces of the blue armchair and the sofa seemed to be in better condition and that is why it was decided to leave them alone. Gilding was mostly missing on higher surfaces and it was decided to re-gild them. This decision became the initial point for finding a uniform solution. I toned the painted concave surfaces with Mica powders and Dammar varnish, covering the earlier unequally painted surfaces with the same stuff.

The white armchair that had been refinished in the 1980s needed special methods. Its gilding and colour matched neither the leaf-gold nor the old bronze paint and so I decided to renew the whole finishing. I coated the new wooden details and the unfinished ones with gesso viide6 ⁽⁶⁾ and bole viide7 ⁽⁷⁾ and gilded them with leaf-gold. [ill 25], [ill 26] Maria Väinsaar, conservator of the Kadriorg Art Museum was a great help when I had to choose the means and methods for finishing.

Covering material

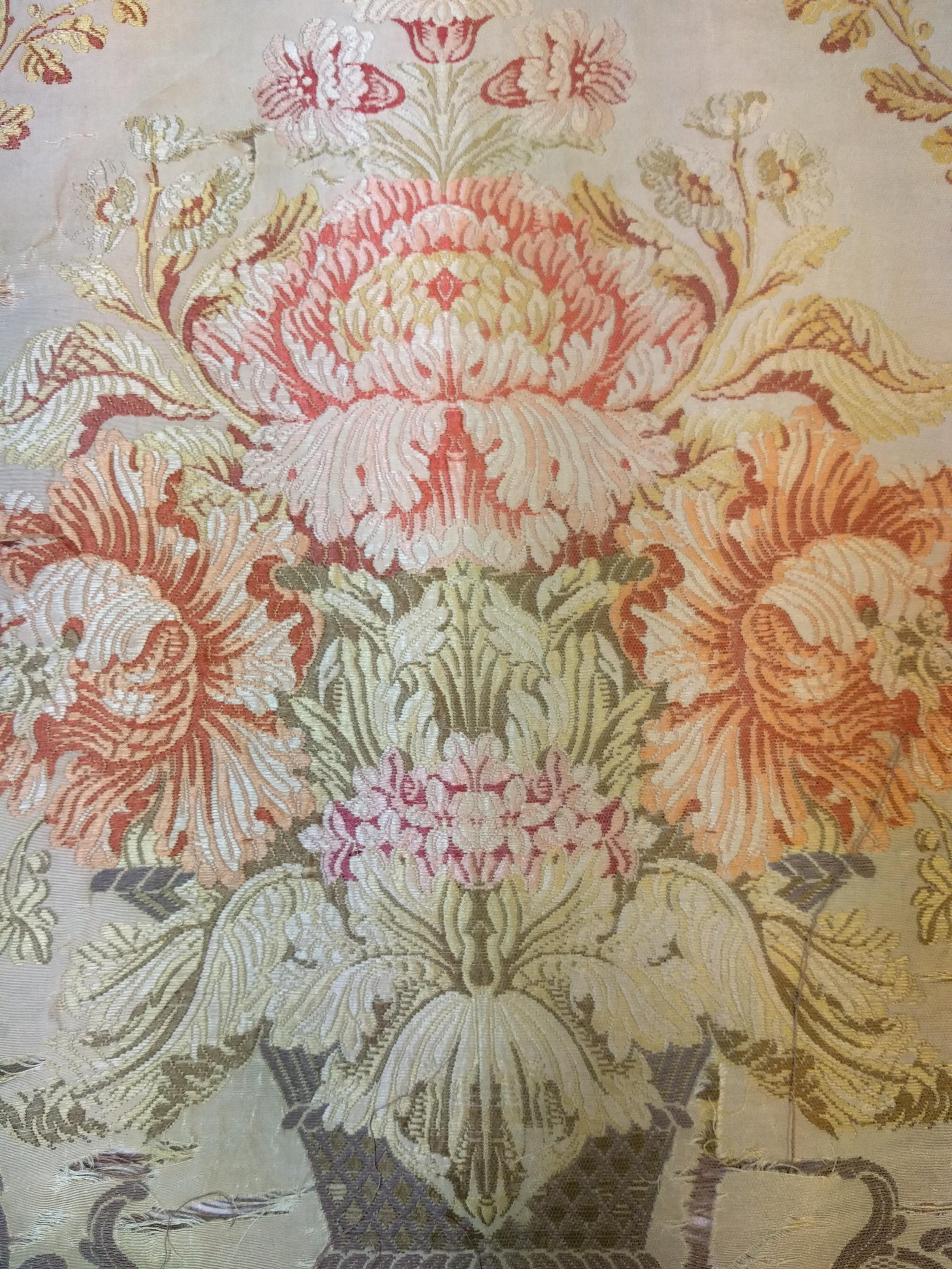

It is a growing trend to appreciate historical seating materials for museum pieces and in private collections alike. As for the Kadriorg Museum’s furniture set the original silk fabric had preserved only on the backs and ‘ears’ of the white armchair and sofa. There is no data on the original fabric of the blue armchair.

The main aim was to preserve as much of the original fabric as possible. The original silk fabric on the white armchair was in stabile condition, although the material was fragile. The fabric that had covered the ‘ears’ of the same armchair had not been conserved or put back but it had still been retained.

The fabric on the arm-supports and the front part of the sofa was so seriously damaged that its pattern had practically disappeared. The colour of the fabric and the metal thread in the upper and lower parts of the fabric differed greatly. Traces of moisture impairment were visible and the reddish copper thread had oxidised, turning green. The light background colour of the silk was spotty – reddish in the upper and green in the lower part. Despite its fragility it was essential to preserve the historic material and as our museum-principles dictate – preserve as found.

Big holes were gaping in the centre of the fabric on the back of the sofa and owing to several tears it was hanging like a dirty rag above the seat. [ill 27], [ill 28]

As an interesting find a light-blue fabric with rococo pattern appeared from beneath the padding on the arm-supports but, unfortunately, the pieces were too small to reconstruct the whole pattern. [ill 29], [ill 30] As similar finds during earlier restoration have not been recorded it is possible that the fabric of similar pattern and coloration was chosen by chance or it might have merely been forgotten to document the choice.

Padding and inner fabrics

The formerly restored upholstery of the armchairs was well preserved and thus there was no need to open it up. Removal of the original fabric from the white armchair would have damaged it more and so I decided to dry-clean the material carefully through netting. The seating material of the blue armchair was removed and dry-cleaned. Working on the sofa brought out interesting material about the arrangement of earlier work, as opening the layers and examining the inner materials provided. The ‘ears’ of the arm-supports of the sofa contained a fine cotton fabric that bore centimetres-wide reddish traces of bole. Thus it can be concluded that bole had been added when the padding was completed up to the interlay. [ill 15] Traces of leaf-gold occurred on the edges of the light-blue fabric that came out from under the arm-supports. This shows that leaf-gold was spread onto the bole after the seating material but before the ornamental ribbon was set.

Comparing the inner fabrics of the sofa it was found that the padding had been partly changed. [ill 14] The traces of bole hinted at the interlay in the ‘ears’ coming from the initial stuffing but the inner material and fabrics in the back differed and were free of bole traces.

The seat padding revealed layers down to the springs and provided me with an opportunity to make necessary repairs in the construction and replace broken details. The nail-holes proved that the springs and saddle-girths as well as the fabric covering them had not been changed. The springs were in good condition – their fixing cords and threads in order and so dry-cleaning the padding seemed sufficient. So I could fix the interlay with nails at their former place. The back padding was also in good condition, the earlier restorers had used horsehair that is a suitable stuffing material indeed. For slight re-freshening I only strengthened the threads on the back a bit, as they were rather slack.

Conservation of the seating material

The original fabric had preserved on the backs and ‘ears’ of the sofa and white armchair. I dry-cleaned all of the preserved fabric with a mini-tipped vacuum cleaner. Fragile spots were cleaned through netting to avoid needless tugging. Wet cleaning was used only for the removed seating material of the sofa. [ill 31]

I washed the coverings in the foam of detergent suitable for wool and silk and dried them stretched out on a table.

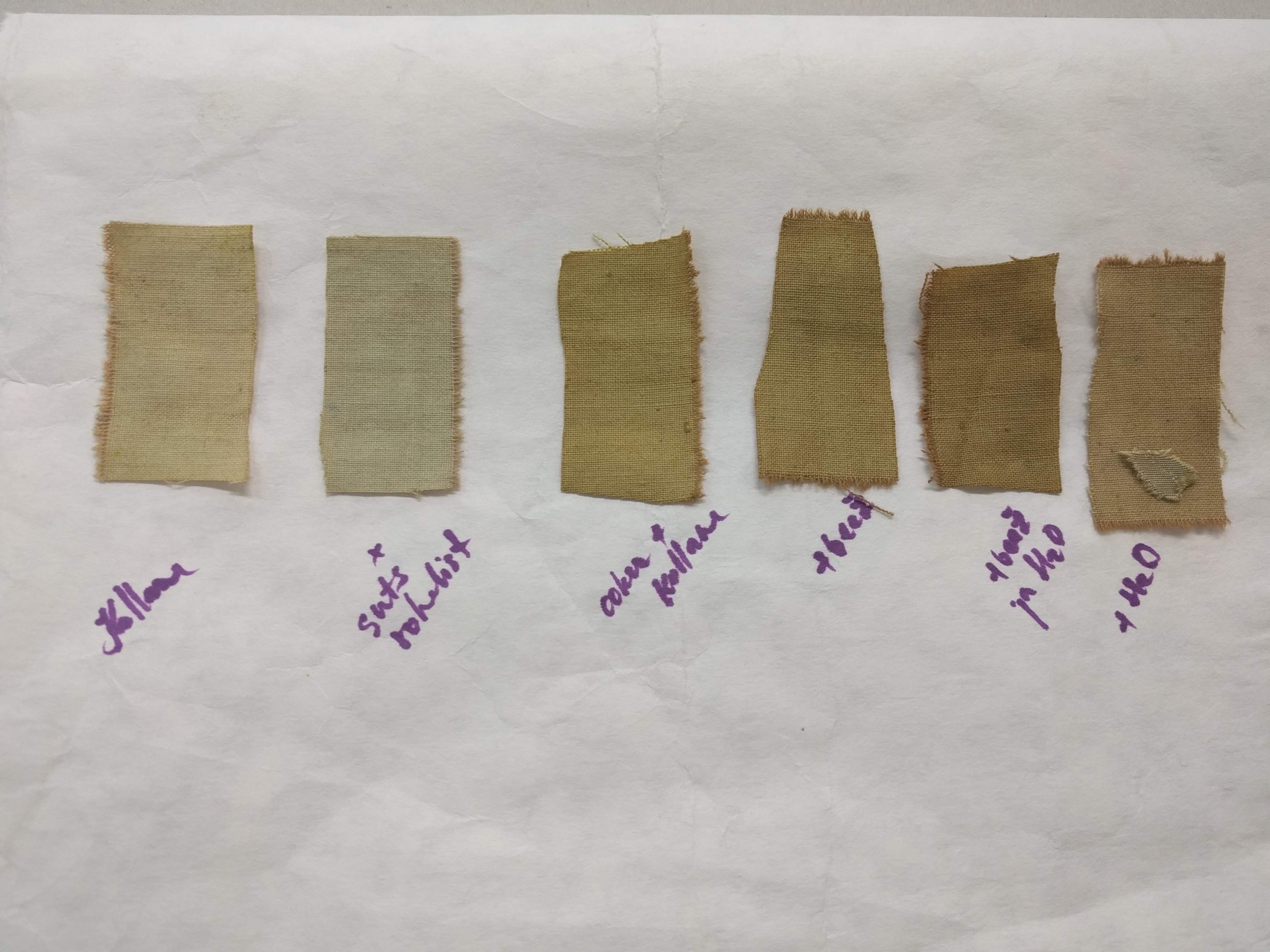

As the fabric on the back of the sofa had rather big rips in it I could not stretch it with common clamps and pins. I used local pressing with filter paper and sandbags only at the places that had seriously damaged weft. [ill 32], [ill 33] As the aim was to fix the original fabric at its initial place the damaged pieces had to be locally lined. The colouring of the patterned fabric on the back was uneven – the upper part had reddish and the lower greenish shade – I decided to mend the rips and losses with local patching. [ill 34], [ill 35] For mending I used natural silk toned with acidic dyes (four shades in all) and silk thread. [ill 36]

At first I was planning to use the sandwich method, in which case the original fabric is sewn between two layers of lining along the edges of rips. This method would have avoided sewing through the original fabric that might have damaged the silk more. We tested various materials and shades viide8 ⁽⁸⁾ [ill 37], but finally decided only to line the preserved fabric. [ill 38] I had had to consider the distinction of padding, where every next layer is a bit smaller than the one above it. Another problem would have been to achieve equable tension in the fabric with several rips and tears in it. The result, i.e. lining to support the fabric was good enough to last until I had fixed it on the back.

The borders of the original fabric that were fragile, torn and with holes in them needed a special care. Gluing the ornamental ribbon on silk and then removing the glue mechanically had caused most of the damage. The rusting nails had had their role to play as well. The borders had to be strengthened before the fabric could be fixed on wood. Lining the border again would have taken too much time and cause pressure tension spots, where the fabric could rip more. That is why I decided to use adhesive material to reinforce the border. Ruth Paas, textile conservator of the Kanut was a great help with her advice for planning the conservation.

Alas, there is not enough fabric…

Considering the partly preserved seating material and the claim of the museum for a complete restoration of the set I had to find a way, how to replace the missing parts of the original fabric. There are several possibilities to order a replica that is similar fabric. It was deliberated whether to choose an analogue or fabric woven of alternative materials or to use printed fabric. The cost of each choice was certainly essential.

Reconstruction or creating a similar fabric of authentic materials is a long and complicated process. Generally it is not known where and when the original fabric was made. In addition to the examination of the material and technology, the ply, evenness, colour and web pattern of the thread or yarn have to be precisely determined. This is what makes the restoration of a high-priced seating material so costly and time-consuming, undertaken only when the furniture is really unique and valuable. We thought about another possibility that would have been weaving a new fabric of alternative materials that would have been cheaper. Contemporary materials offer various possibilities and are easier to preserve. So, for example, we could have used viscose thread instead of silk and metal-plastic instead of copper brocade.

Printing a replica was the third idea. It means that the pattern is printed on a fabric that is as similar to the original as possible. This method has been known already since the 19th century and in case of the Kadriorg set it would have been a modern solution.

Together with the museum we deliberated all the possibilities and our conclusion was to choose the printing. The aim was to imitate the original, preserve the still existing and to unify the losses making them invisible. The commission of the replica was given to the Lipuvabrik (flag factory). Among their fabrics we found a suitable one – a silky polyester fabric that resembled the original one in thickness and density and was not too stretchy.

The similarity of the print as a copy of the original depends on the quality of the image. The biggest piece of fabric with repeated pattern came from the seating material of the sofa. It was digitised in the Kanut photo studio viide9 ⁽⁹⁾ when it had been removed from the sofa, cleaned and stretched. The file was sent to the flag manufactory. [ill 39], [ill 40] Although the image was of high quality it still could not be transferred onto the print fabric in the way the eye sees the colours. The colours needed fine toning. It had to be taken into consideration that the new print and the old fabric would be side by side on the furniture and the wear was different and should not create too noticeable contrasts. The whole process took several months and it turned out that the conservator’s recommendations had been given in terms too hard for the printer to understand and follow. My adjectives (should be duller, more violet, less contrasting, a bit warmer) were too vague and impossible to transfer onto the fabric. [ill 40], [ill 41] I visited the flag factory for several times to make comparisons between the original and the print and finally we achieved the shades that were visually uniform for both – the sofa and the armchair. [ill 42]

None of the pieces had retained its padding cushions. These had been narrowing backwards and had a winding front edge. The blue armchair had got a new padding in an earlier restoration. It was in a right size but had lost its proper shape. The photos of the palace interior from the 1930s showed rather high padding that obviously had feather filling that was common to the time. I made new padding modelling it after the photos and filled them with feathers. [ill 43] In addition I made dust sheets of Tyvek for all the pieces. [ill 44]

Summary

Furniture conservation and restoration require knowledge in art history and styles of furniture, as well as know-how in finishing materials and –methods together with technical knowledge and skill. Every stage in conservation is exciting and provides wonderful experience in combining various materials. Collaboration of conservators with divergent specialities opens new vistas and choices made on this base are more to the point. A good start for learning the conservation history of any object would be studying the documentation and then, if possible, taking the object carefully apart. All its layers and later additions are part of its history, reflecting the values and principles of their time. Information on the Kadriorg furniture has sustained the value of the set. When displayed a single piece, as well as the whole set are important. Due to changing materials it is always complicated to collate the old and the new, the new has not been used and so is not worn. [ill 45], [ill 46] [ill 47] It is exciting to find contemporary local solutions that correspond to the conservation technique and quality requirements and so help to build up a new entity while not losing the old. [ill 48]

The research and practical conservation of the furniture set were completed in 2020, being also Tuuli Trikkant’s MA thesis at the Estonian Academy of Art, the department of cultural heritage and conservation.

The conservation work was nominated for the 2021 Ministry of Culture annual prize (Muuseumirott/Museum rat). The furniture set was displayed at the Kadriorg Art Museum exhibition Stylish Things. Furniture and Decorative Art in the Collections of Estonian Museums (18 May 2022 – 4 September 2022). [ill 49]

Viited

The foreign collection of the Estonian Art Museum has a subsection of foreign applied art and furniture. The furniture collection consists of pieces made in the 18th-20th centuries in Russia and West Europe. Several of the sets have been used in Kadriorg Palace, where they are displayed now and then, at present the set under discussion is at the current exhibition. ↩︎

Dating comes from a manuscript restoration report made in the 1980s. According to this report J. Kuuskemaa, researcher of the Estonian Art Museum asked T.Smolovaya to attribute the pieces using a photo from the Hermitage collection in 1971. ↩︎

Telephone conversation with Mati Raal, 2 April 2019. Author’s notes. ↩︎

Raal, Mati. Restoration passport. KRD-86 document no. 4. Archive of the Kanut. ↩︎

The original fabric of the back – silk-brocade – was conserved in 1985. Textile conservator Heige Peets made it during the training courses of the Lithuanian Art Museum conservation centre. In 1988 a note was published in the journal Renovatum Anno that described the condition of the fabric and its conservation. The fabric was dirty all over, revealed mildew spots, its metal thread had oxidised causing greenish spots. Rust spots (due to fixing nails) and traces of glue, broken metal thread and rips were on the edges of the fabric. During conservation the old glue was removed, metal thread was cleaned off oxidation traces and the material was wet-cleaned with neutral detergent. [https://media.voog.com/0000/0048/7241/files/renovatum (https://media.voog.com/0000/0048/7241/files/renovatum)_1988.pdf. Damaged silk was lined for the first time in the Kanut then. The lining was coated with acrylic glue A-45K and fixed with thermal processing on the back of the original fabric – the method had been worked out in Lithuania. See: Heige Peets. Conservation of textiles in Estonia. Lining textile fabric. Renovatum Anno 2010, https://media.voog.com/0000/0048/7241/files/renovatum_2010_a.pdf

After the restoration of the armchair and the conservation of its fabric it was displayed in Riga at the Estonian section of the First Triennial of the Baltic Conservators in 1986. Textile conservator of the Kanut, Merike Neidorp prepared the armchair for display. ↩︎Gesso priming has been made of chalk and rabbit-skin glue. It is used to prepare the surface for gilding. The layers (10 or more usually) are added, gradually thinning the mixture until the surface is satisfactory. ↩︎

Bole is fine red, orange or yellow clay that is used in gilding for giving the leaf-gold depth, a glow. Mixed with rabbit-skin glue it is the last layer before leaf-gold. ↩︎

To find a good solution and have a better conception I used fabrics that the Kanut possessed. Real silk in various shades (crepeline, France): white, beige, yellow, dark brown, light brown (on the left in the photo) and thin nylon fabric, thicker white netting with small holes, white and toned polyester netting. ↩︎

Jaanus Heinla, the Kanut photographer digitised the fabric using Linhof Master Digi Repro System. ↩︎